Nanook of the North is a 1922 American silent film that combines elements of documentary and docudrama/docufiction, at a time when the concept of separating films into documentary and drama did not yet exist. In the tradition of what would later be called salvage ethnography, the film follows the struggles of the Inuk man named Nanook and his family in the Canadian Arctic. It is written and directed by Robert J. Flaherty, who also served as cinematographer, editor, and producer.

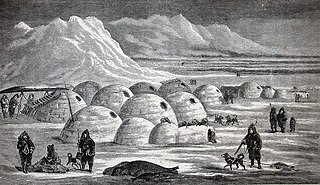

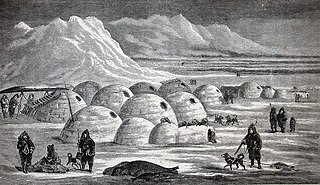

An igloo, also known as a snow house or snow hut, is a type of shelter built of suitable snow.

The Thule or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by 1000 AD and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture who had previously inhabited the region. The appellation "Thule" originates from the location of Thule in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer's Midden.

Mukluks or kamik are soft boots, traditionally made of reindeer (caribou) skin or sealskin, and worn by Indigenous Arctic peoples, including Inuit, Iñupiat, and Yup'ik.

An ulu is an all-purpose knife traditionally used by Inuit, Iñupiat, Yupik, and Aleut women. It is used in applications as diverse as skinning and cleaning animals, cutting a child's hair, cutting food, and sometimes even trimming blocks of snow and ice used to build an igloo. They are widely sold as souvenirs in Alaska.

A quinzhee or quinzee is a Canadian snow shelter made from a large pile of loose snow that is shaped, then hollowed. This is in contrast to an igloo, which is built up from blocks of hard snow, and a snow cave, constructed by digging into the snow. The word is of Athabaskan origin and entered the English language by 1984. A quinzhee can be made for winter camping and survival purposes, or for fun.

Muktuk is a traditional food of Inuit and other circumpolar peoples, consisting of whale skin and blubber. A part of Inuit cuisine, it is most often made from the bowhead whale, although the beluga and the narwhal are also used. It is usually consumed raw, but can also be eaten frozen, cooked, or pickled.

Clavering Island is a large island in eastern Greenland off Gael Hamke Bay, to the south of Wollaston Foreland.

Kivallirmiut, also called the Caribou Inuit, barren-ground caribou hunters, are Inuit who live west of Hudson Bay in Kivalliq Region, Nunavut, between 61° and 65° N and 90° and 102° W in Northern Canada.

Inuit are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon (traditionally), Alaska, and Chukotsky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. Inuit languages are part of the Eskimo–Aleut languages, also known as Inuit-Yupik-Unangan, and also as Eskaleut. Inuit Sign Language is a critically endangered language isolate used in Nunavut.

Copper Inuit, also known as Inuinnait and Kitlinermiut, are a Canadian Inuit group who live north of the tree line, in what is now the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut and in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories. Most of them historically lived in the area around Coronation Gulf, on Victoria Island, and southern Banks Island.

The Inuit are an indigenous people of the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America. The ancestors of the present-day Inuit are culturally related to Iñupiat, and Yupik, and the Aleut who live in the Aleutian Islands of Siberia and Alaska. The term culture of the Inuit, therefore, refers primarily to these areas; however, parallels to other Eskimo groups can also be drawn.

The qulliq or kudlik, is the traditional oil lamp used by many circumpolar peoples, including the Inuit, the Chukchi and the Yupik peoples. The fuel is seal-oil or blubber, and the lamp is made of soapstone. A qulliq is lit with a stick called a taqqut.

Deltaterrasserne is a pre-Inuit occupation archaeological site located near the head of Jørgen Brønlund Fjord on the Peary Land peninsula in northern Greenland. It is one of the largest archaeological sites in Peary Land, and was discovered in September 1948 by the Danish explorer and archaeologist Eigil Knuth during the second summer of the Danish Pearyland Expedition. Occupied during the period of 2,050–1,750 BC, the site contains features of Independence I and Independence II cultures.

Central Inuit are the Inuit of Northern Canada, their designation determined by geography and their tradition of snowhouses ("igloos"), fur clothing, and sled dogs. They are differentiated from Alaska's Iñupiat, Greenland's Kalaallit, and Russian Inuit. Central Inuit are subdivided into smaller groupings which include the Caribou, Netsilik, Iglulik, and Baffinland Inuit. Though Copper Inuit are geographically located in the central Arctic, they are considered to be socially and ideologically distinct from the Central Inuit.

A snow knife or snow saw is a tool used in the construction of igluit or as a weapon by Inuit of the Arctic. The snow knife was originally made from available materials such as bone or horn but the Inuit adapted to using metal after the arrival of Europeans. It may also be used for digging for berries or as a prop in storytelling.

The tupiq is a traditional Inuit tent made from seal or caribou skin. An Inuk was required to kill five to ten ugjuk to make a sealskin tent. When a man went hunting he would bring a small tent made out of five ugjuit. A family tent would be made of ten or more ugjuit.

Cultures from pre-history to modern times constructed domed dwellings using local materials. Although it is not known when or where the first dome was created, sporadic examples of early domed structures have been discovered. Brick domes from the ancient Near East and corbelled stone domes have been found from the Middle East to Western Europe. These may indicate a common source or multiple independent traditions. A variety of materials have been used, including wood, mudbrick, or fabric. Indigenous peoples around the world produce similar structures today.

Traditional Inuit clothing is a complex system of cold-weather garments historically made from animal hide and fur, worn by Inuit, a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic areas of Canada, Greenland, and the United States. The basic outfit consisted of a parka, pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots. The most common sources of hide were caribou, seals, and seabirds, although other animals were used when available. The production of warm, durable clothing was an essential survival skill which was passed down from women to girls, and which could take years to master. Preparation of clothing was an intensive, weeks-long process that occurred on a yearly cycle following established hunting seasons. The creation and use of skin clothing was strongly intertwined with Inuit religious beliefs.

In Inuit culture, sipiniq refers to a person who is believed to have changed their physical sex as an infant, but whose gender is typically designated as being the same as their perceived original sex. In some ways, being sipiniq can be considered a third gender. In Inuit Nunaat this concept is primarily attested in areas of the Canadian Arctic, such as Igloolik and Nunavik, as well in Greenland such as Kitaamiut Inuit and Inughuit, though Iiviit used the words tikkaliaq and nuliakaaliaq. The Netsilik Inuit used the word kipijuituq for a similar concept.