Mellieħa is a large village in the Northern Region of Malta. It has a population of 10,087 as of March 2014. Mellieħa is also a tourist resort, popular for its sandy beaches, natural environment, and Popeye Village nearby.

Nadur is an administrative unit of Malta, located in the eastern part of the island of Gozo. Nadur is built on a plateau and is one of the largest localities in Gozo. Known as the 'second city', it spreads along a high ridge to the east of Victoria. It had a population of 4,509 as of March 2014.

The Megalithic Temples of Malta are several prehistoric temples, some of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites, built during three distinct periods approximately between 3600 BC and 2500 BC on the island country of Malta. They had been claimed as the oldest free-standing structures on Earth until the discovery of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. Archaeologists believe that these megalithic complexes are the result of local innovations in a process of cultural evolution. This led to the building of several temples of the Ġgantija phase, culminating in the large Tarxien temple complex, which remained in use until 2500 BC. After this date, the temple-building culture disappeared.

Manikata is a small settlement in the limits of Mellieħa in the northwestern part of Malta. It oversees the farming areas in the valley between il-Ballut and il-Manikata. The village's population of 539 is spread among 40 families.

Malta is for non-local government purposes divided into districts as opposed to the local government regions at the same level. The three main types of such districts – statistical, electoral at national level, and policing – have no mainstream administrative effect as the regions and local councils function as the only administrative divisions of the country.

The coastline of Malta consists of bays, sandy beaches, creeks, harbours, small villages, cities, cliffs, valleys, and other interesting sites. Here, there is a list of these different natural features that are found around the coast of Malta.

The Ta' Ħaġrat temples in Mġarr, Malta are recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with several other Megalithic temples. They are amongst the world's oldest religious sites. The larger Ta' Ħaġrat temple dates from the Ġgantija phase ; the smaller temple is dated to the Saflieni phase.

The Gozitan First Division, known for sponsorship reasons as the BOV GFL First Division, is the top division of the Gozo Football League, the league competition for men's football clubs in Gozo.

Post codes in Malta are seven-character strings that form part of a postal address in Malta. Post codes were first introduced in 1991 by the mail operator MaltaPost. Like those in the United Kingdom and Canada, they are alphanumeric.

In Malta, most of the main roads are in the outskirts of the localities to connect one urban area with another urban area. The most important roads are those that connect the south of the island with the northern part, like Tal-Barrani Road, Aldo Moro Street in Marsa and Birkirkara Bypass.

Gozo Region is one of five regions of Malta. The region includes the islands of Gozo, Comino and several little islets such as Cominotto. The region does not border any other regions, but it is close to the Northern Region.

A Gozo Farmhouse is a type of dwelling in Gozo, Malta. Because of the many foreign occupations that Maltese islands have been through, the trading roads that were opened across the Mediterranean Sea and its numerous original influences, Malta and Gozo earned a very rich architectural heritage.

The Devil's Farmhouse, also known in Maltese as Ir-Razzett tax-Xitan, and officially as Ir-Razzett Tax-Xjaten, is an 18th-century farmhouse in Mellieħa, Malta. The farmhouse features two unconnected buildings. The original scope for the buildings was to function as stables and a horse-riding school (Cavalerizza).

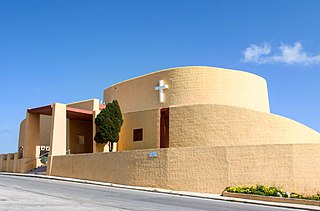

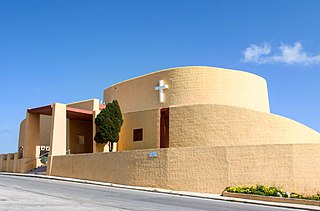

The Parish Church of Saint Joseph is an iconic Roman Catholic parish church in Manikata, Malta, dedicated to Saint Joseph. It was designed by Richard England in 1962, and it was built between 1964 and 1974. The church marks a break from traditional church building designs, and it is an example of Critical regionalism. Its form is inspired by the girna, a traditional corbelled stone hut.

The 2019–20 Maltese FA Trophy was the 82nd edition of the football cup competition.

The 2019–20 Gozo First Division was the 73rd season of the Gozo Football League First Division, the highest division in Gozitan football. The season started on 20 September 2019. Victoria Hotspurs were the defending champions after winning their thirteenth title in the previous season.

Mikiel Fsadni was a Maltese Dominican friar and historian. He is best known for the discovery of Il-Kantilena, the oldest known text in the Maltese language, together with Godfrey Wettinger in 1966.

The 2022–23 season was the annual competitive association football season in Gozo organised by the Gozo Football Association for 2022–23.