Climate and currents

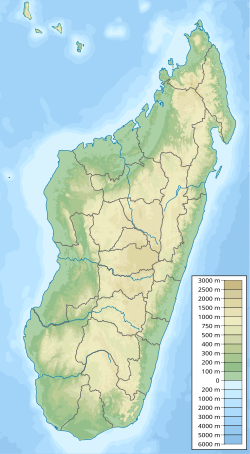

In South Africa, weather patterns are inconsistent. People who live in Madagascar have learned to deal with these conditions. The Agulhas Current is a root cause of these sporadic conditions. Along the South African coast, near Madagascar, the oceanic current, when mixed with a cold front, can cause freak waves that can destroy ships. [7] This current is the largest current to follow adjacent to a continent for that distance. Being on the border of the Indian Ocean gyre, the intense ranges of water temperatures can result in major storms. Tropical storms that have turned into recorded cyclones, have caused billions of dollars' worth of damages. Each cyclone originally forming from the north-eastern coast of the African continent, and slowly accumulating down the coast, where its energy accumulates the most. The storms that result from combining warm and cold temperatures have a huge affect in the northern region of the Agulhas Current. [8] As it goes down the continent of Africa, the atmosphere becomes warmer, and the weather mellows out into a steady rainfall, giving South Africa and West Madagascar humidity and storms. Another factor contributing to weather conditions in the South African- Madagascar region is the contribution of the South Equatorial Madagascar Current. This particular current travels westward from the Indian Ocean, hitting the east coast of Madagascar. This can be a challenge for ships traveling on the east coast of Madagascar because instead of being able to follow the oceans strong general current, they would have to fight it, no matter which way they were traveling. As the SEMC continues South Equatorial Madagascar Current hits Madagascar, the current changes position southward, where it meets up with the stronger Agulhas current, creating conflicting currents that can be a huge hassle for anyone trying to navigate those waters. [9]

Data collection

To gain better research and knowledge about these climate changes, buoys are cast out to sea where they are located by satellite. The satellite pics up these frequencies sent out by the buoys drifting in the ocean off the continental coast, producing much needed data to increase predictability. Original technology of the buoy can date back thirty years, but with advancements in technology, the data collected nowadays do not just focus on the oceanic currents. Information gathered can reflect the wind patterns, temperatures, and certain densities of the ocean in specific areas, as all these factors are constantly fluctuating. These buoys are located all over the world, oceans and great lakes. The data collected goes to the National Data Buoy Center, where experts record and analyze the feedback. With relation to wave currents, the buoys use accelerometers that can identify the directional vector of the waves. They also record the special distance between the trough and crest of each wave. This information that is constantly used by sailors, can be life saving and result in a more efficient trip across the sea. [10]

2008 Mass stranding

A mass stranding of around one hundred Melon-Headed whales (Peponocephala Electra) occurred in the Loza Lagoon system of Northwest Madagascar during the months of May and June in 2008. Of the original whales that entered the lagoon system, seventy five died from causes related to being out of their normal deep sea habitat. At the time of the event many marine experts, conservation organizations, and other groups surveyed the area to collect data on this event. The International Whaling Agency (IWC) and other federal agencies with the permission of the Madagascar Government launched an investigation into the cause of this mass stranding. The IWC concluded that the most plausible trigger for the event was a high power 12 kHz multi-beam echosounder system (MBES) that has been firing along a shelf break a day before the event. [11]