CIA cryptonyms are code names or code words used by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to refer to projects, operations, persons, agencies, etc.

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service and later absorbed by the National Security Agency (NSA), that ran from February 1, 1943, until October 1, 1980. It was intended to decrypt messages transmitted by the intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union. Initiated when the Soviet Union was an ally of the US, the program continued during the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was considered an enemy.

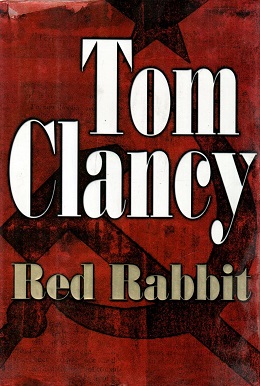

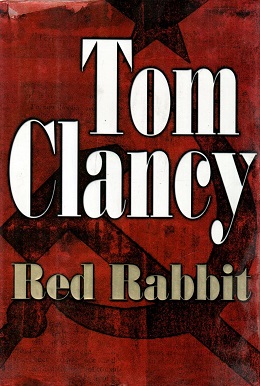

Red Rabbit is a spy thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on August 5, 2002. The plot occurs a few months after the events of Patriot Games (1987), and incorporates the 1981 assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II. Main character Jack Ryan, now an analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency, takes part in the extraction of a Soviet defector who knows of a KGB plot to kill the pontiff. The book debuted at number one on The New York Times Best Seller list.

The Directorate-General for External Security is France's foreign intelligence agency, equivalent to the British MI6 and the American CIA, established on 2 April 1982. The DGSE safeguards French national security through intelligence gathering and conducting paramilitary and counterintelligence operations abroad, as well as economic espionage. It is headquartered in the 20th arrondissement of Paris.

A sleeper agent is a spy or operative who is placed in a target country or organization, not to undertake an immediate mission, but instead to act as a potential asset on short notice if activated. Even if not activated, the "sleeper agent" is still an asset and can still play an active role in sedition, espionage, or possibly treason by virtue of agreeing to act if activated. A team of sleeper agents may be referred to as a sleeper cell. A sleeper cell or agent may possibly be working with others in a clandestine cell system.

The Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation or FIS RF is Russia's external intelligence agency, focusing mainly on civilian affairs. The SVR RF succeeded the First Chief Directorate (PGU) of the KGB in December 1991. The SVR has its headquarters in the Yasenevo District of Moscow with its director reporting directly to the President of the Russian Federation.

The First Main Directorateof the Committee for State Security under the USSR council of ministers was the organization responsible for foreign operations and intelligence activities by providing for the training and management of covert agents, intelligence collection administration, and the acquisition of foreign and domestic political, scientific and technical intelligence for the Soviet Union.

Oleg Vladimirovich Penkovsky, codenamed Hero and Yoga was a Soviet military intelligence (GRU) colonel during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Penkovsky informed the United States and the United Kingdom about Soviet military secrets, including the appearance and footprint of Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile installations and the weakness of the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program. This information was decisive in allowing the US to recognize that the Soviets were placing missiles in Cuba before most of them were operational. It also gave US President John F. Kennedy, during the Cuban Missile Crisis that followed, valuable information about Soviet weakness that allowed him to face down Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and resolve the crisis without a nuclear war.

A cover in foreign, military or police human intelligence or counterintelligence is the ostensible identity and/or role or position in an infiltrated organization assumed by a covert agent during a covert operation.

Philip Burnett Franklin Agee was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) case officer and writer of the 1975 book, Inside the Company: CIA Diary, detailing his experiences in the CIA. Agee joined the CIA in 1957, and over the following decade had postings in Washington, D.C., Ecuador, Uruguay and Mexico. After resigning from the Agency in 1968, he became a leading opponent of CIA practices. A co-founder of the CounterSpy and CovertAction series of periodicals, he died in Cuba in January 2008.

Anatoliy Mikhaylovich Golitsyn CBE was a Soviet KGB defector and author of two books about the long-term deception strategy of the KGB leadership. He was born in Pyriatyn, USSR. He provided "a wide range of intelligence to the CIA on the operations of most of the 'Lines' (departments) at the Helsinki and other residencies, as well as KGB methods of recruiting and running agents." He became an American citizen by 1984.

As early as the 1920s, the Soviet Union, through its GRU, OGPU, NKVD, and KGB intelligence agencies, used Russian and foreign-born nationals, as well as Communists of American origin, to perform espionage activities in the United States, forming various spy rings. Particularly during the 1940s, some of these espionage networks had contact with various U.S. government agencies. These Soviet espionage networks illegally transmitted confidential information to Moscow, such as information on the development of the atomic bomb. Soviet spies also participated in propaganda and disinformation operations, known as active measures, and attempted to sabotage diplomatic relationships between the U.S. and its allies.

Richard Skeffington Welch was a career Central Intelligence Agency officer. He was the Chief of Station (COS) in Athens, Greece, when he was assassinated by the Revolutionary Organization 17 November (17N). His assassination led to the passage of the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, making it a crime to expose or identify officers working in covert roles who had not officially been acknowledged as such by the U.S. government.

The Mitrokhin Archive refers to a collection of handwritten notes about secret KGB operations spanning the period between the 1930s and 1980s made by KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin which he shared with the British intelligence in the early 1990s. Mitrokhin, who had worked at KGB headquarters in Moscow from 1956 to 1985, first offered his material to the US' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Latvia, but they rejected it as possible fakes. After that, he turned to the UK's MI6, which arranged his defection from Russia.

Yuri Ivanovich Nosenko was a putative KGB officer who ostensibly defected to the United States in 1964. Controversy arose as to whether or not he was a KGB "plant," and he was held in detention by the CIA for over three years. Eventually, he was deemed a true defector. After his release he became an American citizen and worked as a consultant and lecturer for the CIA.

The Clandestine HUMINT page adheres to the functions within the discipline, including espionage and active counterintelligence.

Clandestine HUMINT asset recruiting refers to the recruitment of human agents, commonly known as spies, who work for a foreign government, or within a host country's government or other target of intelligence interest for the gathering of human intelligence. The work of detecting and "doubling" spies who betray their oaths to work on behalf of a foreign intelligence agency is an important part of counterintelligence.

The Committee for State Security, abbreviated as KGB, was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, OGPU, and NKVD. Attached to the Council of Ministers, it was the chief government agency of "union-republican jurisdiction", carrying out internal security, foreign intelligence, counter-intelligence and secret police functions. Similar agencies operated in each of the republics of the Soviet Union aside from the Russian SFSR, where the KGB was headquartered, with many associated ministries, state committees and state commissions.

The CIA Kennedy assassination is a prominent John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory. According to ABC News, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is represented in nearly every theory that involves American conspirators. The secretive nature of the CIA, and the conjecture surrounding the high-profile political assassinations in the United States during the 1960s, has made the CIA a plausible suspect for some who believe in a conspiracy. Conspiracy theorists have ascribed various motives for CIA involvement in the assassination of President Kennedy, including Kennedy's firing of CIA director Allen Dulles, Kennedy's refusal to provide air support to the Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy's plan to cut the agency's budget by 20 percent, and the belief that the president was weak on communism. In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) concluded that the CIA was not involved in the assassination of Kennedy.

Russian espionage in the United States has occurred since at least the Cold War, and likely well before. According to the United States government, by 2007 it had reached Cold War levels.