A sex worker is a person who provides sex work, either on a regular or occasional basis. The term is used in reference to those who work in all areas of the sex industry. According to one view, sex work is voluntary "and is seen as the commercial exchange of sex for money or goods". Thus it differs from sexual exploitation, or the forcing of a person to commit sexual acts.

Nevada is the only U.S. state where prostitution is legally permitted in some form. Prostitution is legal in 10 of Nevada's 17 counties, although only six allow it in every municipality. Six counties have at least one active brothel, which mainly operate in isolated, rural areas. The state's most populated counties, Clark and Washoe, are among those that do not permit prostitution. It is also illegal in Nevada's capital, Carson City, an independent city.

Sex work is "the exchange of sexual services, performances, or products for material compensation. It includes activities of direct physical contact between buyers and sellers as well as indirect sexual stimulation". Sex work only refers to voluntary sexual transactions; thus, the term does not refer to human trafficking and other coerced or nonconsensual sexual transactions such as child prostitution. The transaction must take place between consenting adults of the legal age and mental capacity to consent and must take place without any methods of coercion, other than payment. The term emphasizes the labor and economic implications of this type of work. Furthermore, some prefer the use of the term because it grants more agency to the sellers of these services.

Prostitution in the Netherlands is legal and regulated. Operating a brothel is also legal. De Wallen, the largest and best-known Red-light district in Amsterdam, is a destination for international sex tourism.

COYOTE is an American sex workers' rights organization. Its name is a backronym for Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics, a reflection of the fact that sex work tends to be stigmatized primarily because of society-imposed standards of ethics. COYOTE's goals include the decriminalization of prostitution, pimping and pandering, as well as the elimination of social stigma concerning sex work as an occupation. Its work is considered part of the larger sex worker movement for legal and human rights.

Prostitution in South Africa is illegal for both buying and selling sex, as well as related activities such as brothel keeping and pimping. However, it remains widespread. Law enforcement is poor.

A Vindication of The Rights of Whores is a 1989 anthology edited by Gail Pheterson with a preface by Margo St. James.

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact with the customer. The requirement of physical contact also creates the risk of transferring infections. Prostitution is sometimes described as sexual services, commercial sex or, colloquially, hooking. It is sometimes referred to euphemistically as "the world's oldest profession" in the English-speaking world. A person who works in the field is usually called a prostitute or sex worker, but other words, such as hooker and whore, are sometimes used pejoratively to refer to those who work in prostitution. The majority of prostitutes are female and have male clients.

Prostitution in Cuba is not officially illegal; however, there is legislation against pimps, sexual exploitation of minors, and pornography. Sex tourism has existed in the country, both before and after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Many Cubans do not consider the practice immoral. In Cuban slang, female prostitutes are called Jineteras, and gay male prostitutes are called Jineteros or Pingueros. The terms literally mean "jockey" or "rider", and colloquially "sexual jockey", and connote sexual control during intercourse. The terms also have the broader meaning of "hustler", and are related to jineterismo, a range of illegal or semi-legal economic activities related to tourism in Cuba. Stereotypically a Jinetera is represented as a working-class Afro-Cuban woman. Black and mixed-race prostitutes are generally preferred by foreign tourists seeking to buy sex on the island. UNAIDS estimates there are 89,000 prostitutes in the country.

Sex workers' rights encompass a variety of aims being pursued globally by individuals and organizations that specifically involve the human, health, and labor rights of sex workers and their clients. The goals of these movements are diverse, but generally aim to legalize or decriminalize sex work, as well as to destigmatize it, regulate it and ensure fair treatment before legal and cultural forces on a local and international level for all persons in the sex industry.

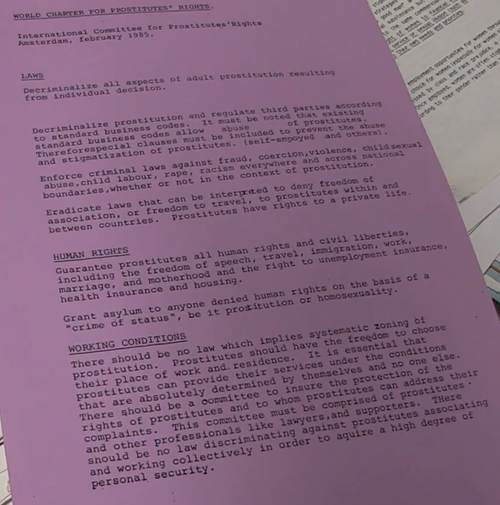

The European Sex Workers' Rights Alliance (ESWA) is a sex worker-led network for sex workers' rights, representing more than 100 organisations led by or working with sex workers in 30 countries in Europe and Central Asia. It was originally formed as the International Committee for Prostitutes' Rights (ICPR) in 1985, and since its relaunch in 2005 known as the International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe (ICRSE), registered as a nonprofit foundation in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The organisation adopted its current name ESWA in 2021.

Prostitution laws varies widely from country to country, and between jurisdictions within a country. At one extreme, prostitution or sex work is legal in some places and regarded as a profession, while at the other extreme, it is considered a severe crime punishable by death in some other places. A variety of different legal models exist around the world, including total bans, bans that only target the customer, and laws permitting prostitution but prohibiting organized groups, an example being brothels.

Survival sex is a form of prostitution engaged in by people because of their extreme need. It can include trading sex for food, a place to sleep, or other basic needs; it can also be used to obtain addictive drugs. Survival sex is engaged in by homeless people, refugees, asylum seekers, and others disadvantaged in society.

Migrant sex work is sex work done by migrant workers. It is significant because of its role as a dominant demographic of sex work internationally. It has common features across various contexts, such as migration from rural to urban areas and from developing to industrialized nations, and the economic factors that help to determine migrant status. Migrant sex workers have also been the subject of discussions concerning the legality of sex work, its connection to sex trafficking, and the views of national governments and non-governmental organizations about the regulation of sex work and the provision of services for victims of sex trafficking.

International Whores' Day or International Sex worker's Day is observed annually on June 2 of each year, honours sex workers and recognises their often exploited working conditions. The event commemorates the occupation of Église Saint-Nizier in Lyon by more than a hundred sex workers on June 2, 1975 to draw attention to their inhumane working conditions. It has been celebrated annually since 1976. In German, it is known as Hurentag. In Spanish-speaking countries, it is the Día Internacional de la Trabajadora Sexual, the International Day of the Sex Worker.

The decriminalization of sex work is the removal of criminal penalties for sex work. Sex work, the consensual provision of sexual services for money or goods, is criminalized in most countries. Decriminalization is distinct from legalization.

The Nordic Model approach to sex work, also marketed as the end demand, equality model, neo-abolitionism, Nordic and Swedish model, is an approach to sex work that criminalises clients, third parties and many ways sex workers operate. This approach to criminalising sex work was developed in Sweden in 1999 on the debated radical feminist position that all sex work is sexual servitude and no person can consent to engage in commercial sexual services. The main objective of the model is to abolish the sex industry by punishing the purchase of sexual services. The model was also originally developed to make working in the sex industry more difficult.

Sex worker abuse by police officers can occur in one or more ways. Police brutality refers to the intentional use of excessive force by a police officer, be it physical, verbal, or psychological. Police corruption is a form of police misconduct where an officer obtains financial benefits and/or career advancements in exchange for not pursuing, or selectively pursuing, an investigation or arrest. Police misconduct refers to inappropriate actions taken by police officers in connection with their official duties. Sex workers, particularly poor sex workers and those who had been manipulated, coerced, or forced into sex work, are at risk of being obliged or otherwise forced to provide free sexual services to police officers out of fear of being harmed or arrested. Some sex workers have reported that they have encountered police officers who have physically assaulted them without evidence of a crime and without making an arrest.

Feminist perspectives on sex markets vary widely, depending on the type of feminism being applied. The sex market is defined as the system of supply and demand which is generated by the existence of sex work as a commodity. The sex market can further be segregated into the direct sex market, which mainly applies to prostitution, and the indirect sex market, which applies to sexual businesses which provide services such as lap dancing. The final component of the sex market lies in the production and selling of pornography. With the distinctions between feminist perspectives, there are many documented instances from feminist authors of both explicit and implied feminist standpoints that provide coverage on the sex market in regards to both "autonomous" and "non-autonomous" sex trades. The quotations are added since some feminist ideologies believe the commodification of women's bodies is never autonomous and therefore subversive or misleading by terminology.

Sex worker movements address issues of labor rights, gender-related violence, social stigma, migration, access to health care, criminalization, and police violence and have evolved to address local conditions and historical challenges. Although accounts of sex work dates back to antiquity, movements organized to defend sex workers' rights are understood as a more recent phenomenon. While contemporary sex worker rights movements are generally associated with the feminist movement of the 1970s and 1980s in Europe and North America, the first recorded sex worker organization, Las Horizontales began in 1888 in Havana, Cuba.