In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

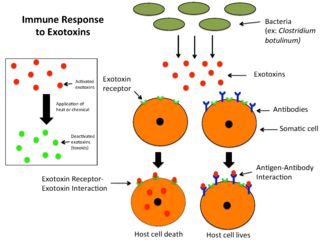

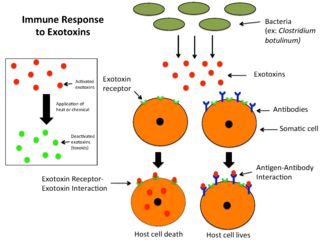

An exotoxin is a toxin secreted by bacteria. An exotoxin can cause damage to the host by destroying cells or disrupting normal cellular metabolism. They are highly potent and can cause major damage to the host. Exotoxins may be secreted, or, similar to endotoxins, may be released during lysis of the cell. Gram negative pathogens may secrete outer membrane vesicles containing lipopolysaccharide endotoxin and some virulence proteins in the bounding membrane along with some other toxins as intra-vesicular contents, thus adding a previously unforeseen dimension to the well-known eukaryote process of membrane vesicle trafficking, which is quite active at the host–pathogen interface.

ATC code J07Vaccines is a therapeutic subgroup of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, a system of alphanumeric codes developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the classification of drugs and other medical products. Subgroup J07 is part of the anatomical group J Antiinfectives for systemic use.

The bacterial capsule is a large structure common to many bacteria. It is a polysaccharide layer that lies outside the cell envelope, and is thus deemed part of the outer envelope of a bacterial cell. It is a well-organized layer, not easily washed off, and it can be the cause of various diseases.

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, sold under the brand name Pneumovax 23, is a pneumococcal vaccine that is used for the prevention of pneumococcal disease caused by the 23 serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae contained in the vaccine as capsular polysaccharides. It is given by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection.

A toxoid is an inactivated toxin whose toxicity has been suppressed either by chemical (formalin) or heat treatment, while other properties, typically immunogenicity, are maintained. Toxins are secreted by bacteria, whereas toxoids are altered form of toxins; toxoids are not secreted by bacteria. Thus, when used during vaccination, an immune response is mounted and immunological memory is formed against the molecular markers of the toxoid without resulting in toxin-induced illness. Such a preparation is also known as an anatoxin. There are toxoids for prevention of diphtheria, tetanus and botulism.

Neisseria meningitidis, often referred to as the meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a coccus because it is round, and more specifically a diplococcus because of its tendency to form pairs.

Pneumococcal vaccines are vaccines against the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae. Their use can prevent some cases of pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis. There are two types of pneumococcal vaccines: conjugate vaccines and polysaccharide vaccines. They are given by injection either into a muscle or just under the skin.

The Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, also known as Hib vaccine, is a vaccine used to prevent Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. In countries that include it as a routine vaccine, rates of severe Hib infections have decreased more than 90%. It has therefore resulted in a decrease in the rate of meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis.

John Bennett Robbins was a senior investigator at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), best known for his contribution to the development of the vaccine against bacterial meningitis Hib)) with his colleague Rachel Schneerson. He conducted research on the Bethesda, Maryland campus of the NIH from 1970 until his retirement at the age of 80 in 2012. During his tenure, he worked in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Food and Drug Administration’s biologics laboratories on location.

The Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine is a typhoid vaccine recommended by the World Health Organization for the prevention of typhoid. The vaccine was first licensed in the US in 1994 and is made from the purified Vi capsular polysaccharide from the Ty2 Salmonella Typhi strain; it is a subunit vaccine.

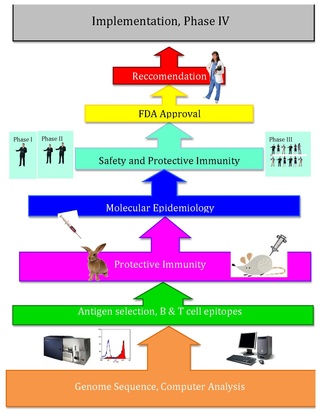

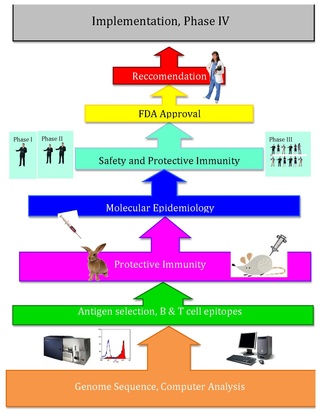

Reverse vaccinology is an improvement of vaccinology that employs bioinformatics and reverse pharmacology practices, pioneered by Rino Rappuoli and first used against Serogroup B meningococcus. Since then, it has been used on several other bacterial vaccines.

Pneumococcal infection is an infection caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A subunit vaccine is a vaccine that contains purified parts of the pathogen that are antigenic, or necessary to elicit a protective immune response. Subunit vaccine can be made from dissembled viral particles in cell culture or recombinant DNA expression, in which case it is a recombinant subunit vaccine.

Immunomics is the study of immune system regulation and response to pathogens using genome-wide approaches. With the rise of genomic and proteomic technologies, scientists have been able to visualize biological networks and infer interrelationships between genes and/or proteins; recently, these technologies have been used to help better understand how the immune system functions and how it is regulated. Two thirds of the genome is active in one or more immune cell types and less than 1% of genes are uniquely expressed in a given type of cell. Therefore, it is critical that the expression patterns of these immune cell types be deciphered in the context of a network, and not as an individual, so that their roles be correctly characterized and related to one another. Defects of the immune system such as autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency, and malignancies can benefit from genomic insights on pathological processes. For example, analyzing the systematic variation of gene expression can relate these patterns with specific diseases and gene networks important for immune functions.

Rachel Schneerson is a former senior investigator in the Laboratory in Developmental and Molecular Immunity and head of the Section on Bacterial Disease Pathogens and Immunity within the Laboratory at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development within the National Institutes of Health. She is best known for her development of the vaccine against bacterial meningitis with her colleague John B. Robbins.

CRM197 is a non-toxic mutant of diphtheria toxin, currently used as a carrier protein for polysaccharides and haptens to make them immunogenic. There is some dispute about the toxicity of CRM197, with evidence that it is toxic to yeast cells and some mammalian cell lines.

Andrew Lees is an American vaccine chemist known for developing the CDAP conjugation method, used in vaccines manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline and conjugate vaccines currently in clinical development by the Serum Institute of India and Chengdu Institute of Biological Products. Currently, Andrew Lees holds 25 patents in the area of conjugate vaccines.

A vaccine dose contains many ingredients very little of which is the active ingredient, the immunogen. A single dose may have merely nanograms of virus particles, or micrograms of bacterial polysaccharides. A vaccine injection, oral drops or nasal spray is mostly water. Other ingredients are added to boost the immune response, to ensure safety or help with storage, and a tiny amount of material is left-over from the manufacturing process. Very rarely, these materials can cause an allergic reaction in people who are very sensitive to them.

Trudy Virginia Noller Murphy is an American pediatric infectious diseases physician, public health epidemiologist and vaccinologist. During the 1980s and 1990s, she conducted research at Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, Texas on three bacterial pathogens: Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Murphy's studies advanced understanding of how these organisms spread within communities, particularly among children attending day care centers. Her seminal work on Hib vaccines elucidated the effects of introduction of new Hib vaccines on both bacterial carriage and control of invasive Hib disease. Murphy subsequently joined the National Immunization Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). where she led multi-disciplinary teams in the Divisions of Epidemiology and Surveillance and The Viral Hepatitis Division. Among her most influential work at CDC was on Rotashield™, which was a newly licensed vaccine designed to prevent severe diarrheal disease caused by rotavirus. Murphy and her colleagues uncovered that the vaccine increased the risk of acute bowel obstruction (intussusception). This finding prompted suspension of the national recommendation to vaccinate children with Rotashield, and led the manufacturer to withdraw the vaccine from the market. For this work Murphy received the United States Department of Health and Human Services Secretary's Award for Distinguished Service in 2000, and the publication describing this work was recognized in 2002 by the Charles C. Shepard Science Award from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.