The Watts riots, sometimes referred to as the Watts Rebellion or Watts Uprising, took place in the Watts neighborhood and its surrounding areas of Los Angeles from August 11 to 16, 1965. The riots were motivated by anger at the racist and abusive practices of the Los Angeles Police Department, as well as grievances over employment discrimination, residential segregation, and poverty in L.A.

A police riot is a riot carried out by the police; more specifically, it is a riot that police are responsible for instigating, escalating or sustaining as a violent confrontation. Police riots are often characterized by widespread police brutality, and they may be done for the purpose of political repression.

The Progressive Labor Party (PLP) is an anti-revisionist Marxist–Leninist communist party in the United States. It was established in January 1962 as the Progressive Labor Movement following a split in the Communist Party USA, adopting its new name at a convention held in the spring of 1965. It was involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement of the 1960s and early 1970s through its Worker Student Alliance faction of Students for a Democratic Society.

Tompkins Square Park is a 10.5-acre (4.2 ha) public park in the Alphabet City portion of East Village, Manhattan, New York City. The square-shaped park, bounded on the north by East 10th Street, on the east by Avenue B, on the south by East 7th Street, and on the west by Avenue A, is abutted by St. Marks Place to the west. The park opened in 1834 and is named for Daniel D. Tompkins, Vice President of the United States.

The East St. Louis massacre was a series of violent attacks between African Americans and white Americans in East St. Louis, Illinois, between late May and early July of 1917. These attacks also displaced 6,000 African Americans and led to the destruction of approximately $400,000 worth of property. They occurred in East St. Louis, an industrial city on the east bank of the Mississippi River, directly opposite the city of St. Louis, Missouri. The July 1917 episode in particular was marked by violence throughout the city. The multi-day rioting has been described as the "worst case of labor-related violence in 20th-century American history", and among the worst racial riots in U.S. history.

The May Day riots of 1894 were a series of violent demonstrations that occurred throughout Cleveland, Ohio on May 1, 1894. Cleveland's unemployment rate increased dramatically during the Panic of 1893. Finally, riots broke out among the unemployed who condemned city leaders for their ineffective relief measures. According to the New York Times, "[t]he desire to stop work seemed to take possession of every laborer..." on May Day of 1894.

Abram Duryée was a Union Army general during the American Civil War, the commander of one of the most famous Zouave regiments, the 5th New York Volunteer Infantry. After the war he was New York City Police Commissioner.

The protests of 1968 comprised a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, which were predominantly characterized by the rise of left-wing politics, anti-war sentiment, civil rights urgency, youth counterculture within the silent and baby boomer generations, and popular rebellions against military states and bureaucracies.

The Tompkins Square Park riot occurred on August 6–7, 1988 in Tompkins Square Park, located in the East Village and Alphabet City neighborhoods of Manhattan, New York City. Groups of "drug pushers, homeless people and young people known as squatters and punks," had largely taken over the park. The East Village and Alphabet City communities were divided about what, if anything, should be done about it. The local governing body, Manhattan Community Board 3, recommended, and the New York City Parks Department adopted a 1 a.m. curfew for the previously 24-hour park, in an attempt to bring it under control. On July 31, a protest rally against the curfew saw several clashes between protesters and police.

Herbert George Gutman (1928–1985) was an American professor of history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he wrote on slavery and labor history.

The Jeltoqsan, also spelled Zheltoksan, or December of 1986, were protests that took place in Alma-Ata, Kazakh SSR, in response to CPSU General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev's dismissal of Dinmukhamed Kunaev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan and an ethnic Kazakh, and his replacement with Gennady Kolbin, an ethnic Russian from the Russian SFSR.

The Remington Rand strike of 1936–1937 was a strike by a federal union affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) against the Remington Rand company. The strike began in May 1936 and ended in April 1937, although the strike settlement would not be fully implemented until mid-1940.

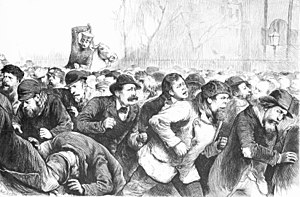

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, United States. The rally began peacefully in support of workers striking for an eight-hour work day; it was held the day after a May 3 rally at a McCormick Harvesting Machine Company plant on the West Side of Chicago, during which two demonstrators had been killed and many demonstrators and police injured. At the Haymarket Square rally on May 4, an unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at the police as they acted to disperse the meeting, and the bomb blast and ensuing retaliatory gunfire by the police caused the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; dozens of others were wounded.

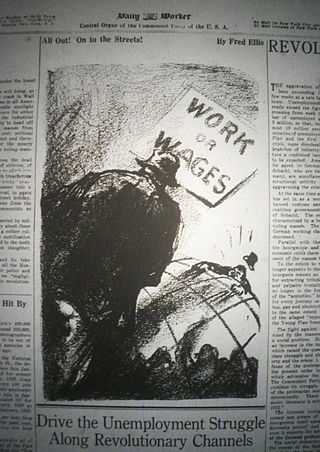

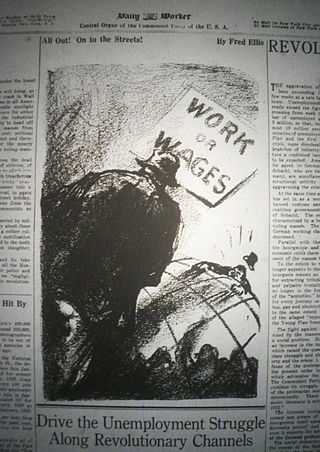

International Unemployment Day was a coordinated international campaign of marches and demonstrations, marked by hundreds of thousands of people in major cities around the world taking to the streets to protest mass unemployment associated with the Great Depression. The Unemployment Day marches, organized by the Communist International and coordinated by its various member parties, resulted in two deaths of protestors in Berlin, injuries at events in Vienna and the Basque city of Bilbao, and less violent outcomes in London and Sydney.

The San Francisco riot of 1877 was a three-day riot waged against Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, California by the city's majority Irish population from the evening of July 23 through the night of July 25, 1877. The ethnic violence which swept Chinatown resulted in four deaths and the destruction of more than $100,000 worth of property belonging to the city's Chinese immigrant population.

The Unemployed Councils of the USA (UC) was a mass organization of the Communist Party, USA established in 1930 in an effort to organize and mobilize unemployed workers.

Joseph Patrick McDonnell was an Irish-American labor leader and journalist. He edited the New York Labor Standard, and was one of the founders of the International Labor Union.

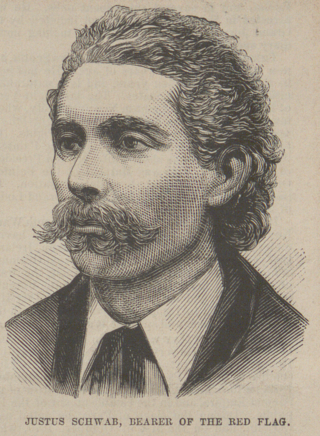

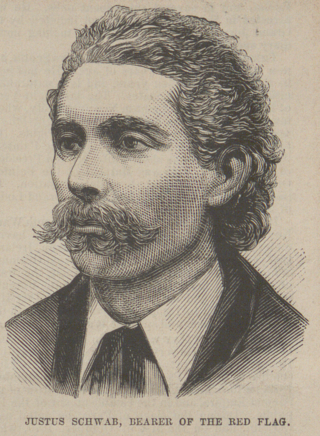

Justus H. Schwab (1847–1900) was the keeper of a radical saloon in New York City's Lower East Side. An emigre from Germany, Schwab was involved in early American anarchism in the early 1880s, including the anti-authoritarian New York Social Revolutionary Club's split from the Socialistic Labor Party and Johann Most's entry to the United States.