Ajaccio is the capital and largest city of Corsica, France. It forms a French commune, prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud, and head office of the Collectivité territoriale de Corse. It is also the largest settlement on the island. Ajaccio is located on the west coast of the island of Corsica, 210 nautical miles (390 km) southeast of Marseille.

Corse-du-Sud is an administrative department of France, consisting of the southern part of the island of Corsica. The corresponding departmental territorial collectivity merged with that of Haute-Corse on 1 January 2018, forming the single territorial collectivity of Corsica, with territorial elections coinciding with the dissolution of the separate council. Although its administrative powers were ceded to the new territorial collectivity, it continues to remain an administrative department in its own right. In 2019, it had a population of 158,507.

The National Liberation Front of Corsica is a name used by various guerrilla and paramilitary organizations that advocate an independent or autonomous state on the island of Corsica, separated from France. The original FLNC was founded on 5 May 1976 from a merger between two smaller armed groups: the Corsican Peasant Front for Liberation, and Ghjustizia Paolina. This organization persisted until 1990, when a 1988 ceasefire agreement caused the unstable organization to split into two organizations based around separate ideas. In 1999, various factions merged to form the FLNC-Union of Combatants, a larger organization and one of the FLNCs which still exist today. In the present day, there are four organizations still active with the FLNC name: The FLNC-UC, The FLNC-22 October, the FLNC-1976, and the FLNC-21 May. The FLNC-UC and FLNC-22U, the two largest and most active groups, often sign press releases and communiqués together, and have been allied since at least 2022. The political party Nazione was founded in 2024 from the political party Corsica Libera, the modern political wing of the FLNC-UC. is led by Petr'Antu Tomasi, Ghjuvan-Guidu Talamoni and Josepha Giacometti-Piredda, with the participation of the former FLNC political prisoner Carlu Santoni. The FLNCs are all mostly local to Corsica but also commit attacks on the French mainland.

The Corsican Assembly or Assembly of Corsica is the unicameral legislative body of the territorial collectivity of Corsica. It has its seat at the Grand Hôtel d'Ajaccio et Continental, in the Corsican capital of Ajaccio. After the 2017 territorial elections, the assembly was expanded from 51 to 63 seats, with the executive council expanding from 9 to 11 members.

Corsica Nazione was an electoral group in the Corsican Assembly composed of Corsican nationalist parties. It was led by Jean-Guy Talamoni, who would later become president of the Corsican Assembly in 2015 under the Corsica Libera political party. The group supported the nationalist paramilitaries of the Corsican conflict, and many of the parties in the coalition were political wings of various armed factions.

The Corsicans are a Romance-speaking ethnic group, native to the Mediterranean island of Corsica, a territorial collectivity of France.

Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the French mainland, west of the Italian Peninsula and immediately north of the Italian island of Sardinia, the nearest land mass. A single chain of mountains makes up two-thirds of the island. As of January 2024, it had a population of 355,528.

Bernard Bonnet, French civil servant, is best known for being the first prefect since World War II to be convicted of an offense committed in the course of his duties, his role in the "Affair of the beach huts".

Corsican nationalism is the concept of a cohesive nation of Corsica and a national identity of its people. The Corsican autonomy movement stems from Corsican nationalism and advocates for further autonomy for the island, if not outright independence from France.

Corsica Libera is a left-wing separatist political party active in Corsica. It was founded in Corte in February 2009 by members of three nationalist parties, Corsica Nazione, Rinnovu and the Corsican Nationalist Alliance.

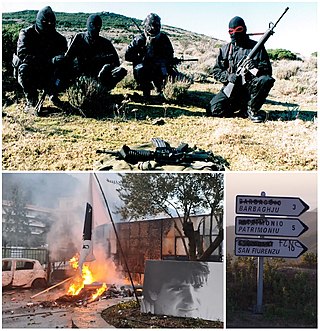

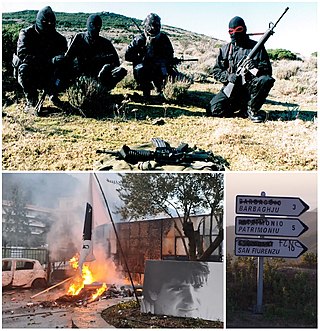

The Corsican conflict is an armed and political conflict on the island of Corsica which began in 1976 between the government of France and Corsican nationalist militant groups, mainly the National Liberation Front of Corsica and factions of the group. Beginning in the 1970s, the Corsican conflict peaked in the 1980s before Corsican nationalist groups and the French government reached a truce with one of the two main splinters of the FLNC, the FLNC-Union of Combattants in June 2014. In 2016, the other main splinter, the FLNC-22nd of October also declared a truce. It is currently ongoing following the 2022 Corsica unrest and the return to arms of the FLNC-UC and FLNC-22U.

Pè a Corsica was a Corsican nationalist political alliance in France, which was calling for more autonomy for Corsica. More specifically, it was a coalition of the two Corsican nationalist parties active on the island; that is, the moderately autonomist Femu a Corsica and the strongly committed separatist Corsica Libera. The party was led by the autonomist Gilles Simeoni. The alliance was renewed for the 2017 territorial election. However, the alliance was dissolved for the 2021 territorial election.

Jean-Guy Talamoni is a Corsican politician and Corsican nationalist, who was President of the Corsican Assembly from 17 December 2015 to 1 July 2021. He previously served as leader of the Corsica Nazione electoral group in the Corsican assembly.

The 2017 Corsican territorial elections were held on 3 and 10 December 2017 to elect 63 members of the Corsican Assembly, who in turn determined the composition of the Executive Council of Corsica. The election was held only two years after the 2015 territorial elections, and were called as a result of the planned creation of a single collectivity within Corsica resulting from the mergers of two departments, and the existing territorial collectivity of Corsica.

Les Jardins de l'Empereur is a neighbourhood of Ajaccio, Corsica, France. The neighbourhood has been described as a banlieue and is classed as a sensitive urban zone (ZUS). The majority of its inhabitants are foreign, of which North Africans predominate. The neighbourhood made national and international headlines due to violent unrest in December 2015, after which programmes were initiated to improve it.

In March 2022, the island of Corsica, France, saw protests in response to a prison attack on nationalist leader Yvan Colonna. There were rallies in the main cities of Ajaccio, Calvi and Bastia that descended into violent clashes between police and protestors. Protestors threw stones and flares at gendarmes.

Corsican autonomy is the idea and movement supporting the status of an autonomous region for the island of Corsica within the French Republic. Most supporters of greater autonomy are Corsican nationalists. The ruling Femu a Corsica party supports an autonomous status for Corsica.

The Aleria standoff was a confrontation between members of the French Gendarmerie and Corsican nationalist militants who entrenched themselves in a wine cellar at Aleria, Corsica, on 21 and 22 August 1975. The armed activists belonged to the radical nationalist party Action Régionaliste Corse (ARC). The occupation resulted in a strong reaction of the French government and is regarded as the precursor of the Corsican conflict.

On 17 August 2001, Corsican guerrilla leader and head of the extremist Armata Corsa organisation François Santoni was shot 13 times while attending the marriage of a family friend. The groom, Jean-René Tomasi, was also injured in the attack. The 6 attackers were mostly members of the Brise de Mer mafia, the largest mafia group in Corsica at the time, with the exception of Ange-Marie Orsoni. The attack was done after Santoni began accusing members of the National Liberation Front of Corsica-Canal Historique, an organisation he resigned from co-leading three years before, of conspiring with the mafia. Despite the factors leading up to the incident, the incident has largely been ruled as personal score-settling without a political motivation. The incident was a major event in modern Corsican history, ending the 12-year long period of infighting known as the Years of Lead.

The National Liberation Front of Corsica, informally known as “the front” was a Corsican nationalist guerrilla and paramilitary organization formed on 5 May 1976. The group formed to violently overthrow French rule in Corsica to establish an independent Corsican state. It was the first group to form during the Corsican conflict, and the first to use the name “National Liberation Front of Corsica”. The group was declared an unlawful organization in 1983 and ordered to dissolve, but continued to operate regardless of the ruling.