Background

Geological history

The South Dunedin plain was first formed about 18,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Period. At the time, the sea level was about 120 metres lower than today and the coastline stretched out as much as 35 km offshore further from its present extant. Following the Last Glacial Period, sea levels rose, reaching their present level about 7,000 years ago. The Otago Harbour was a former stream valley that was flooded during this period. During the post-glacial sea level rise, the South Dunedin plain was covered in ocean. A dune barrier was later formed between St Clair and Lawyers Head through the flow of fine sediment from the Clutha River and other smaller catchments. After the barrier formed, fine sediment accumulated in the waters at the head of the Otago Harbour, causing the sea in that area to became increasingly shallow. The gradual sediment accumulation led to the formation of a coastal wetland known as the South Dunedin plain, which also became a landbridge between the mainland South Island and the Otago Peninsula.

Human settlement and land reclaimation

At the time of European settlement during the mid-19th century, the South Dunedin plain still consisted of salt marshes, wetlands and lagoons. The local vegetation consisted of tussock, rushes and flax. Local Māori people referred to this wetland system as Kaituna (which translates as "eating eels") due to the significant presence of eels in the area. A shallow lagoon also terminated through the salt dunes near contemporary St Clair. This flat coastal area functioned as a drainage basin for the hilly, catchment area that formed the rest of Dunedin. [1] European settlers referred to this area as "The Flat." Since most of Dunedin is hilly, houses were initially built on the slopes of the extinct Dunedin Volcano. As the city's population grew during the Otago gold rush, European settlers began reclaiming swampy land in "The Flat." The land was filled using sand from the coastal dunes of St Kilda. Consequently, much of South Dunedin was built on land consisting of soft, sandy sediment that was only slightly above the water table (which was up to 17 cm lower than the present day). [1] [9]

During the late 19th century, marram grass was planted and sand-catching structures were also built along Ocean Beach, creating high sand dunes south of present-day Victoria Road that runs across St Kilda and St Clair. To accommodate the expansion of housing in South Dunedin, drainage of the wet lands through the dunes was blocked off to prevent storm tides from coming in through these dunes. [9] During the 1960s and 1970s, further land reclamation occurred between Andersons Bay Road and Portsmouth Drive through the use of dredging spoil excavated from Otago Harbour. This reclaimed land was used predominantly for commercial activity and including a pumping station on Portobello Road. Land reclamation, human settlement, and the laying of asphalt and concrete for building roads and buildings in South Dunedin has disrupted the natural drainage basin by preventing water from seeping into the ground. In 2019, Stuff journalist Charlie Mitchell estimated that 60% of South Dunedin was impervious, with some pockets reporting 100%. [1]

Socio-economic demographics

South Dunedin has also historically experienced a high degree of socio-economic deprivation, with parts of the suburb ranking in the bottom 10 percent of the deprivation index. While the median personal income in South Dunedin is NZ$20,100, some pockets reported a record low median income of NZ$14,000. Due to its low-quality housing stock, South Dunedin also reported a high level of residents living in rental homes including low-income earners, people experiencing mental health and emotional issues, and recent migrants. Due to its flat landscape, South Dunedin also reported a significant number of residents using wheelchairs. [1]

Flood event

On 3 June 2015, the coastal parts of the Otago region in the South Island experienced heavy rainfall and high tide, which raised the level of height of the ground water and led to flooding. [12] During the 24 hour period leading to 3pm on 3 June, Dunedin City Council (DCC) civil defence manager estimated that 90–95 mm of rain had fallen in the Dunedin area. [13] The DCC described the June flood event as a "one in a 100 year flood," with about 175mm of rain falling in the 24 hour period between 4 am on 3 June and 4 am on 4 June, exceeding the "one in a 100 year flood" level which was 120mm over 24 hours. [4] [2]

The worst affected suburbs were South Dunedin, Kaikorai Valley, the Brighton coast, the Taieri Plain, North Road and parts of Mosgiel. [13] In response to the rainfall and flooding, residents erected sandbags to protect their properties and businesses. St Clair and Bathgate Park primary schools also sent their pupils home in response to the flooding. [14]

By 12:40 pm, Pine Hill had recorded over 60mm of rain in the past 24 hours. [13] Heavy rain also caused several rivers and streams in North Otago, Dunedin, South Otago and upper Taieri Plain including the Silver Stream, Kaikorai Stream, the Water of Leith, and Lindsay Creek to rise rapidly. Flooding was reported in Kaikorai Valley road, the Gordon Road spillway, and parts of the Taieri Plain and North East Valley. [13] In addition, heavy rainfall caused leaks at several Dunedin Hospital properties, with a blocked city main causing flooding at the Hospital's Lower Ground loading dock. [13]

By noon, MetService duty forecaster Emma Blake reported that 70mm of rain had fallen in coastal Otago during the morning. The meteorological service maintained a heavy rain warning for Dunedin and the Clutha District until 2am on 4 June but forecast that rain would slowly begin easing overnight. Blake forecast that Dunedin would receive a further 80 to 100 mm of rainfall. [14]

The rain eased on 4 June, with Dunedin receiving a total of 175 mm of rain over the past 24 hours. South Dunedin was the hardest hit area, with Labour Member of Parliament for Dunedin South, Claire Curran, describing the suburb as a "major disaster area." [15]

Impact

Dunedin

The heavy rainfall and flooding strained Dunedin's stormwater and sewage systems and road network. By 10:30 am on 3 June, the DCC Water and Waste Network Contracts Manager Mike Ind confirmed that stormwater and sewers in the Hillside Road and Surrey Street areas had reached capacity. By 4pm on 3 February, nine roads around the wider Dunedin area had been closed. New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) urged people to avoid traveling on roads and highways around Dunedin. The NZTA also advised people to avoid travelling on the Dunedin Southern Motorway between Dunedin city centre and Mosgiel. In addition, foul sewer contamination had led to the closure of Hargest Crescent road area. [13] Radio New Zealand later revised the number of affected roads to 15. [14]

By 3 June, Radius Fulton rest home on Dunedin's Hillside Road had been evacuated due to flooding. While some of Radius Fulton's 94 residents managed to seek shelter with family, the rest home had to arrange alternative accommodation for 78 residents. [14] Multiple slips were also reported in the Otago peninsula including Taiaroa Head, which obstructed travel in the area. [4] [2] Two drivers also escaped after their cars were swallowed up by a sinkhole in the Otago peninsula. [2]

East Taieri

In response to surface flooding, power utilities company Aurora Energy cut power to 160 homes in the East Taieri area until the floodwaters subside and power could be safely restored, affecting 517 consumers. [13] [15] By 4 June, Auroa Energy had restored power to the affected homes. [15]

South Otago

Surface flooding was also reported in the Clutha District, leading to the closure of several roads including Lakeside Road at the railway underbridge, Akatore Road at Big Creek, Papatowai Highway at Caberfeidh Hill, Karoro Creek, Mt Wallace Road, Back Road, Springfield Road, Allison Road, and Remote Road. [13] [2]

Tasman-Nelson region

Over 50mm of rain fell in the Tasman–Nelson region of the upper South Island between the mornings of 2 and 3 June 2015, resulting in properties and paddocks being flooded. [2] In addition, Cable Bay near Nelson experienced heavy rain and flooding. [2]

Responses

Emergency response

In response to the flooding, emergency services established an operations centre at the civil defence bunker in Dunedin Central to coordinate their response to the various flooding events across Dunedin. [13] On 4 June, Fire Service personnel also commenced pumping activities throughout South Dunedin. [4] The Southern District Health Board (SDHB) also established an emergency operations centre to ensure that staff were able to travel safely to and from work. The SDHB also assisted several age residential care facilities in Dunedin including finding placement breaks. [13]

During the June flood event, Civil Defence Controller Ruth Stokes confirmed that Civil Defence's Dunedin call centre had received over 3,000 calls over the last 24 hours. On 4 June, Civil Defence visited over 200-flood damaged properties. [15] On 4 June the Fire Service also responded to 345 events, with 90% being in the South Dunedin area. 20 additional Police officers were deployed in South Dunedin to deter looting. [2] In addition, Fire Service Area Commander Lawrence Voight confirmed that firefighters had responded to 130 calls for assistance. [15]

The New Zealand Army was also placed on alert in Mosgiel in the event that the Silver Stream burst its banks. On 3 June, an Army Unimog was used to evacuate children from the flood-stricken Abbotsford School. [14] The Army also helped volunteers sandbag 100 homes in the coastal Dunedin suburb of St Kilda in response to flooding. [2] Houses in South Dunedin's Cutten Street were evacuated with New Zealand Red Cross volunteers visiting households to conduct wellness chats. [2]

Local government

On 3 June, the Civil Defence Welfare Committee and Dunedin City Council also established a welfare centre at South Dunedin Presbyterian Church to provide advice and assistance to affected residents. [2] [4] The New Zealand Red Cross, Police and DCC also visited residences and properties in flood-affected areas of Dunedin to provide safety and welfare checks. The DCC and emergency services also discouraged motorists from driving in flood-affected areas to avoid creating "bow waves" that push flood waters into properties. [4]

On 4 June, Mayor of Dunedin Dave Cull established a mayoral fund to assist flood victims. He stated that the DCC's priority was to get people's flood homes dried and habitable, which would take a few days. The Council also settled displaced residents in motels. Since several roads in the Dunedin area had been damaged by the flood, the DCC and Civil Defence appealed for volunteers to assist with sandbagging, sweeping streets and cleaning homes. [15]

Schools and colleges

As a result of the flooding, all primary and intermediate schools in Dunedin, and early childhood centres affiliated with the Dunedin Kindergarten Association (DKA) closed on 3 June. In addition, Taieri College in Mosgiel and King's High School and Queen's High School in South Dunedin closed. [4] [2] However, Otago Polytechnic's Dunedin campus remained opened. [4]

Aftermath

Damages

In 2017, a University of Otago study estimated that at least 800 homes in the South Dunedin area had been flooded. [12] In 2019, Stuff journalist Charlie Mitchell estimated that around 1,200 homes and businesses in South Dunedin had been damaged by water. The insurance company IAG New Zealand estimated that total flood damage amounted to NZ$138 million (including NZ$28 million in insurance payouts, NZ$64 million in economic damage, and NZ$18 million in social damage). [1]

Criticism of the Dunedin City Council

The Dunedin City Council attracted criticism from local residents including Neil Ivory for failing to maintain drain systems, which worsened the impact of the flooding in parts of Dunedin. In response, DCC road maintenance Peter Stranding said that the city's stormwater system had reached saturation point and could only cope with a certain level of rain. He stated that the mud tanks were full to capacity and discharging onto Dunedin's roading network. [14]

On 21 June 2016, the DCC admitted during a public meeting that a faulty pumping station had made the flood in South Dunedin 20cm deeper. DCC chief executive Sue Bidrose told members of the public that the flooding was caused more by heavy rainfall than an overwhelmed stormwater system. In response, the Council had repaired the pumping station, cleared all drains and mud tanks in South Dunedin, and adopted new procedures to deal with heavy rain. Mayor Cull drew criticism for not attending the public meeting since he was visiting China. In response to allegations from the South Dunedin Action Group that the DCC was planning to abandon South Dunedin and blame it on climate change, Bidrose stated that the Council had invested NZ$5 million in the South Dunedin community hub, NZ$500,000 in a local hockey turf, and was planning to expand the local Gasworks Museum. [5]

In September 2016, the DCC and Otago Regional Council (ORC) launched a series of eight public meetings to discuss the impact of the 2015 flood in South Dunedin and to discuss future planning. Attendees were shown a presentation on the environmental history of South Dunedin and the impact of climate change. Local government officials including ORC director for engineering, hazards and science Gavin Palmer and DCC chief executive Bidrose fronted these talks. [16]

Climate change adaptation

On 20 November 2015, a report released by Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Jan Wright on rising sea levels estimated that 2,800 homes and businesses in South Dunedin were at risk from sea level rises of half a metre caused by climate change. [17] Of this figure, 2,700 homes lay less than 50cm of the high tide mark, with over 70% being situated lower than half that elevation. [18] [1] Due to climate change, rising global temperatures were forecast to melt ice caps, causing sea levels to rise and creating more storms and flooding. In response to the report, Mayor Cull described rising sea levels as a serious issue facing South Dunedin due to its high population density and older, poorer population. [17]

In response to the 2015 Otago flood, the DCC launched a series of workshops in March 2021 to seek community feedback on the future of the South Dunedin coastline between St Clair and St Kilda. [19]

On 25 February 2023, Victoria University of Wellington emeritus professor of public policy Dr Jonathan Boston identified Dunedin as vulnerable to rising sea levels in the near future due to climate change. In the wake of the 2023 Auckland Anniversary Weekend floods and Cyclone Gabrielle, Boston advocated a managed retreat strategy for flood-prone and low-lying areas including South Dunedin, which would involve property buyouts and cooperation between central and local governments. [20]

On 23 June 2023, the DCC's South Dunedin Future programme manager Jonathan Rowe confirmed that the Council was discussing plans to deal with climate change-related challenges facing South Dunedin including rising groundwater, rising sea levels, and increased rainfall. Rowe confirmed that the DCC was considering managed retreat as an option. He clarified that it did not mean abandoning the suburb but potentially strategically evacuating from some areas and intensifying development in other areas. While St Clair Action Group co-chair Richard Egan expressed support for the DCC's planning process for South Dunedin, Ray Macleod of the Greater South Dunedin Action Group criticised managed retreat as amounting to an abandonment of the community. [21]

On 5 September, Mayor of Dunedin Jules Radich confirmed that the DCC had commenced talks with the New Zealand Treasury to secure funding to purchase properties in flood-prone parts of South Dunedin as part of the Council's climate adaptation strategy. [22]

On 29 November 2023, the Otago Daily Times reported that Kāinga Ora had paused funding for building new homes in South Dunedin due to its geographical vulnerability to flooding, erosion, and other natural hazards. [23] On 30 November, the South Dunedin Future Programme proposed 16 options for helping South Dunedin adapt to climate change including designing roads and parks to be floodable, land elevation, waterproofing the ground floor of buildings, restricting development in flood-prone areas, creating water detention basins, elevating the level of houses, and modifying drainage systems. [24]

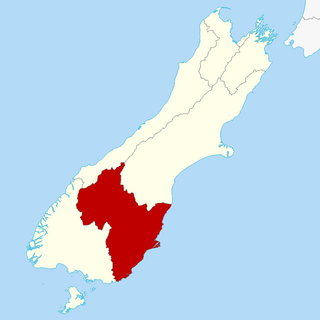

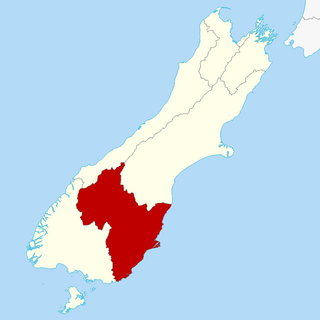

Otago is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately 32,000 square kilometres (12,000 sq mi), making it the country's second largest local government region. Its population was 254,600 in June 2023.

Middlemarch is a small town in the Otago region of New Zealand's South Island. It lies at the foot of the Rock and Pillar Range of hills in the broad Strath-Taieri valley, through which flows the middle reaches of the Taieri River. Since local government reorganisation in the late 1980s, Middlemarch and much of the Strath-Taieri has been administered as part of Dunedin city, the centre of which lies some 80 km to the southeast. Middlemarch is part of the Taieri electorate, and is currently represented in parliament by Ingrid Leary. Middlemarch has reticulated sewerage but no reticulated water supply. A description of 1903, that "[T]he summer seasons are warm, but not enervating, and the winters cold, but dry" is still true today.

The Clutha River is the second longest river in New Zealand and the longest in the South Island. It flows south-southeast 338 kilometres (210 mi) through Central and South Otago from Lake Wānaka in the Southern Alps to the Pacific Ocean, 75 kilometres (47 mi) south west of Dunedin. It is the highest volume river in New Zealand, and the swiftest, with a catchment of 21,000 square kilometres (8,100 sq mi), discharging a mean flow of 614 cubic metres per second (21,700 cu ft/s). The river is known for its scenery, gold-rush history, and swift turquoise waters. A river conservation group, the Clutha Mata-Au River Parkway Group, is working to establish a regional river parkway, with a trail, along the entire river corridor.

Dunedin is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. The city has a rich Māori, Scottish, and Chinese heritage.

Mosgiel is an urban satellite of Dunedin in Otago, New Zealand, fifteen kilometres west of the city's centre. Since the re-organisation of New Zealand local government in 1989 it has been inside the Dunedin City Council area. Mosgiel has a population of approximately 14,800 as of June 2023. A nickname for Mosgiel is "The pearl of the plain". Its low-lying nature does pose problems, making it prone to flooding after heavy rains. Mosgiel takes its name from Mossgiel Farm, Ayrshire, the farm of the poet Robert Burns, the uncle of the co-founder in 1848 of the Otago settlement, the Reverend Thomas Burns.

The Taieri River is the fourth-longest river in New Zealand and is in Otago in the South Island. Rising in the Lammerlaw Range, it initially flows north, then east around the Rock and Pillar range before turning southeast, reaching the sea 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of Dunedin.

The Taieri Plain is an area of fertile agricultural land to the southwest of Dunedin, in Otago, New Zealand. The plain covers an area of some 300 square kilometres, with a maximum extent of 30 kilometres. It is not to be confused with Strath Taieri, a second plain of the Taieri River, 40kms to the north beyond Mount Ross.

Brighton is a small seaside town within the city limits of Dunedin on New Zealand's South Island. It is located 20 kilometres southwest from the city centre on the Southern Scenic Route.

Dunedin Railways is the trading name of Dunedin Railways Limited, an operator of a railway line and tourist trains based at Dunedin Railway Station in the South Island of New Zealand. The company is a council-controlled trading organisation wholly owned by Dunedin City Council through its holding company Dunedin City Holdings Limited.

Taieri Mouth is a small fishing village at the mouth of the Taieri River, New Zealand. Taieri Island (Moturata) lies in the ocean several hundred metres off the river's mouth.

The Strath Taieri is a large glacial valley and river plateau in New Zealand's South Island. It is surrounded by the rugged hill ranges to the north and west of Otago Harbour. Since 1989 it has been part of the city of Dunedin. The small town of Middlemarch is located at its southern end.

George Street is the main street of Dunedin, the second largest city in the South Island of New Zealand. It runs for two and a half kilometres north-northeast from The Octagon in the city centre to the foot of Pine Hill. It is straight and undulates gently as it skirts the edge of the hills to its northwest. South of The Octagon, Princes Street continues the line of George Street south-southwest for two kilometres.

Outram is a rural suburb of Dunedin, New Zealand, with a population of 880 as of June 2023. It is located 28 kilometres west of the central city at the edge of the Taieri Plains, close to the foot of Maungatua. The Taieri River flows close to the southeast of the town. Outram lies on State Highway 87 between Mosgiel and Middlemarch.

Allanton is a small town in Otago, New Zealand, located some 20 kilometres southwest of Dunedin on State Highway 1. The settlement lies at the eastern edge of the Taieri Plains close to the Taieri River at the junction of the main road to Dunedin International Airport at Momona.

Dunedin Hospital is the main public hospital in Dunedin, New Zealand. It serves as the major base hospital for the Otago and Southland regions with a potential catchment radius of roughly 300 kilometres, and a population of around 120,000.

South Dunedin is a major inner city suburb of the New Zealand city of Dunedin. It is located, as its name suggests, 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) to the south of the city centre, on part of a large plain known locally simply as "The Flat". The suburb is a mix of industrial, retail, and predominantly lower-quality residential properties.

Calton Hill is an elevated southern residential suburb of the City of Dunedin in New Zealand's South Island. The suburb is named after Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland, and some of its street names carry similar etymological roots.

Taieri is a parliamentary electorate in the Otago region of New Zealand, initially from 1866 to 1911, and was later recreated during the 2019/20 electoral redistribution ahead of the 2020 election.

The cyclone of 1929 was an unnamed tropical cyclone that struck New Zealand in mid-March 1929 causing widespread flooding and destruction.

Jules Vincent Radich is a New Zealand politician who has served as the 59th mayor of Dunedin, New Zealand since 2022. He has also served as councillor for the Dunedin City Council since 2019. Radich also serves as deputy Chair of Infrastructure and sits as a member on the Saddle Hill Community Board.