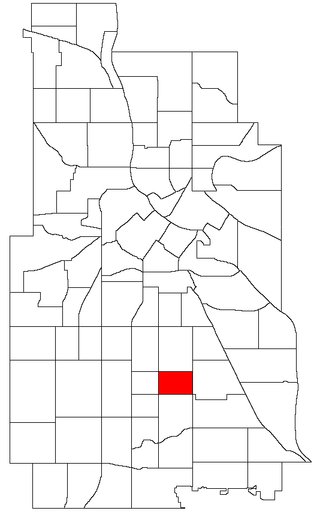

The Central neighborhood of Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States is located south of the downtown region of the city. It is bounded by Lake Street on the north, Chicago Avenue on the east, 38th Street on the south, and Interstate 35W on the west. It should not be confused with the Central community, which covers Downtown and some surrounding neighborhoods.

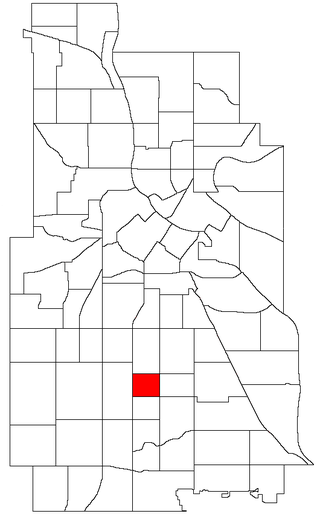

Whittier is a neighborhood within the Powderhorn community in the U.S. city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, bounded by Franklin Avenue on the north, Interstate 35W on the east, Lake Street on the south, and Lyndale Avenue on the west. It is known for its many diverse restaurants, coffee shops and Asian markets, especially along Nicollet Avenue. The neighborhood is home to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and the Children's Theatre Company.

Minneapolis is officially defined by its city council as divided into 83 neighborhoods. The neighborhoods are historically grouped into 11 communities. Informally, there are city areas with colloquial labels. Residents may also group themselves by their city street suffixes: North, Northeast, South, and Southeast.

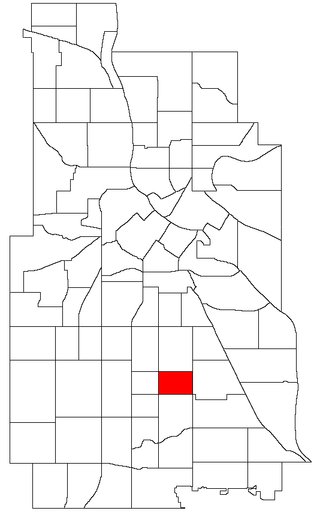

Powderhorn Park is a neighborhood within the larger Powderhorn community of Minneapolis. The neighborhood is located approximately three miles south of downtown and is bordered by East Lake Street to the north, Cedar Avenue to the east, East 38th Street to the south, and Chicago Avenue to the west. Its namesake is the city's Powderhorn Park facility in the northwestern part of the neighborhood around Powderhorn Lake.

Lowry Hill East, also known as the Wedge because of its wedge-like shape, is a neighborhood in southwest Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, part of the Calhoun Isles community. It is bounded on the east by Lyndale Avenue, on the west by Hennepin Avenue and on the south by Lake Street. Lyndale and Hennepin intersect on the northern side at Interstate 94. This creates a neighborhood roughly triangular in shape.

Lake Street is a major east-west thoroughfare between 29th and 31st streets in Minneapolis, Minnesota United States. From its western most end at the city's limits, Lake Street reaches the Chain of Lakes, passing over a small channel linking Bde Maka Ska and Lake of the Isles, and at its eastern most end it reaches the Mississippi River. In May 2020, the Lake Street corridor suffered extensive damage during local unrest following the murder of George Floyd. In August of the same year, city officials designated East Lake Street as one of seven cultural districts to promote racial equity, preserve cultural identity, and promote economic growth.

Loring Park is a neighborhood in the Central Community of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Located on the southwest corner of downtown Minneapolis, it also lends its name to Loring Park, the largest park in the neighborhood. The official boundaries of the neighborhood are Lyndale Avenue to the west, Interstate 394 to the north, 12th Street to the northeast, Highway 65 to the east, and Interstate 94 to the south. It is located in Minneapolis City Council Ward 7, represented by Katie Cashman.

Bancroft is a neighborhood within the Powderhorn community in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. Its boundaries are East 38th Street to the north, Chicago Avenue to the west, East 42nd Street to the south and Cedar Avenue to the east. It is entirely located within Minneapolis City Council Ward 8, represented by Andrea Jenkins.

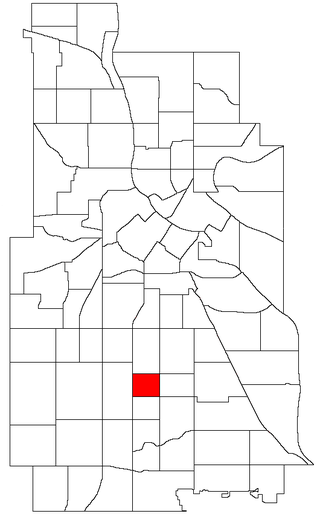

Bryant is a neighborhood within the Powderhorn community in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. Its boundaries are East 38th Street to the north, Chicago Avenue to the east, East 42nd Street to the south, and Interstate 35W to the west. It is entirely located within Minneapolis City Council Ward 8 represented by councilmember Andrea Jenkins, and Minnesota Senate District 62.

Robert Lilligren is an American politician and member of the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party. He was an elected member of the Minneapolis City Council. He was first elected in 2001, to represent the 8th Ward of the Minneapolis City Council. Following the defeat of Green Party member Dean Zimmermann, during the 2005 municipal elections, Lilligren represented the 6th Ward of the City of Minneapolis. When first elected to office, Lilligren was serving as a volunteer on eight different community boards and commissions including: vice-chair of Phillips West Neighborhood organization, the Midtown Greenway Coalition, the Hennepin County-appointed I-35W Project Advisory Committee, and as a board member for several affordable housing groups throughout South Minneapolis. He lost his re-election bid in 2013 to Abdi Warsame. He was appointed to the Metropolitan Council by Governor Tim Walz in March 2019.

King Field is a neighborhood in the Southwest community in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Its boundaries are 36th Street to the north, Interstate 35W to the east, 46th Street to the south, and Lyndale Avenue to the west. King Field, within the King Field neighborhood is a park named after Martin Luther King Jr.

Powderhorn is a defined community in Minneapolis, that consists of eight neighborhoods. The community name is derived from Powderhorn Lake that is the centerpiece of the present-day Powdernhorn Park. Located south of downtown, the community also features the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Hennepin History Museum, the Midtown Greenway trail, and numerous other establishments, many of which serve the Latin American and African diaspora.

Minneapolis is often considered one of the top biking and walking cities in the United States due to its vast network of trails and dedicated pedestrian areas. In 2020, Walk Score rated Minneapolis as 13th highest among cities over 200,000 people. Some bicycling ratings list Minneapolis at the top of all United States cities, while others list Minneapolis in the top ten. There are over 80 miles (130 km) of paved, protected pathways in Minneapolis for use as transportation and recreation. The city's Grand Rounds National Scenic Byway parkway system accounts for the vast majority of the city's shared-use paths at approximately 50 miles (80 km) of dedicated biking and walking areas. By 2008, other city, county, and park board areas accounted for approximately 30 miles (48 km) of additional trails, for a city-wide total of approximately 80 miles (130 km) of protected pathways. The network of shared biking and walking paths continued to grow into the late 2010s with the additions of the Hiawatha LRT Trail gap remediation, Min Hi Line pilot projects, and Samatar Crossing. The city also features several natural-surface hiking trails, mountain-biking paths, groomed cross-country ski trails in winter, and other pedestrian walkways.

Local protests over the murder of George Floyd, sometimes called the Minneapolis riots or the Minneapolis uprising, began on May 26, 2020, and within a few days had inspired a global protest movement against police brutality and racial inequality. The initial events were a reaction to a video filmed the day before and circulated widely in the media of police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck for several minutes while Floyd struggled to breathe, begged for help, lost consciousness, and died. Public outrage over the content of the video gave way to widespread civil disorder in Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and other cities in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area over the five-day period of May 26 to 30 after Floyd's murder.

False rumors of a police shooting resulted in rioting, arson, and looting in the U.S. city of Minneapolis from August 26–28, 2020. The events began as a reaction to the suicide of Eddie Sole Jr., a 38-year old black man who was being pursued by Minneapolis police officers for his alleged involvement in a homicide. At approximately 2 p.m. on August 26, Sole died after he shot himself in the head as officers approached to arrest him. False rumors quickly spread on social media that Minneapolis police officers had fatally shot Sole. To quell unrest, Minneapolis police released closed-circuit television surveillance footage that captured Sole's suicide, which was later confirmed by a Hennepin County Medical Examiner's autopsy report.

As a reaction to the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, racial justice activists and some residents of the Powderhorn community in Minneapolis staged an occupation protest at the intersection of East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue with a blockade of the streetway lasting over a year. The intersection is where Derek Chauvin, a white police officer with the Minneapolis Police Department, murdered George Floyd, an unarmed 46-year-old Black man. Activists erected barricades to block vehicular traffic and transformed the intersection and surrounding structures with amenities, social services, and public art depicting Floyd and other racial justice themes. The community called the unofficial memorial and protest zone at the intersection "George Floyd Square". The controversial street occupation in 2020 and 2021 was described as an "autonomous zone" and a "no-go" place for police, but local officials disputed the extent of such characterizations.

The U.S. city of Minneapolis featured officially and unofficially designated camp sites in city parks for people experiencing homelessness that operated from June 10, 2020, to January 7, 2021. The emergence of encampments on public property in Minneapolis was the result of pervasive homelessness, mitigations measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota, local unrest after the murder of George Floyd, and local policies that permitted encampments. At its peak in the summer of 2020, there were thousands of people camping at dozens of park sites across the city. Many of the encampment residents came from outside of Minneapolis to live in the parks. By the end of the permit experiment, four people had died in the city's park encampments, including the city's first homicide victim of 2021, who was stabbed to death inside a tent at Minnehaha Park on January 3, 2021.

Civil unrest began in the Uptown district of the U.S. city of Minneapolis on June 3, 2021, as a reaction to news reports that law enforcement officers had killed a wanted suspect during an arrest. The law enforcement killing occurred atop a parking ramp near West Lake Street and Girard Avenue. Police fired several rounds, killing the person at the scene. In an initial statement about the encounter, the U.S. Marshals Service alleged that a person failed to comply with arresting officers and produced a gun. Crowds gathered on West Lake Street near the parking ramp soon afterwards as few details were known about the incident or the deceased person, who was later identified as Winston Boogie Smith, a 32-year-old black American man.

George Floyd Square, officially George Perry Floyd Square, is a memorialized streetway in Minneapolis for the section of Chicago Avenue that intersects East 38th Street. It is named after George Floyd, a black man who was murdered there by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020. The commemorative street name is signed along Chicago Avenue between East 37th Street to East 39th Street and includes the 38th and Chicago intersection.