Facts

As a result of the Suez Crisis some mining properties of the appellant Anisminic (renamed from Sinai Mining Co.) located in the Sinai peninsula were seized by the Egyptian government before November 1956. The appellants then sold the mining properties to The Economic Development Organisation (TEDO), an Egyptian government owned organisation, in 1957.

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the tripartite aggression in the Arab world and Sinai War in Israel, was an invasion of Egypt in late 1956 by Israel, followed by the United Kingdom and France. The aims were to regain Western control of the Suez Canal and to remove Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had just nationalized the canal. After the fighting had started, political pressure from the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Nations led to a withdrawal by the three invaders. The episode humiliated the United Kingdom and France and strengthened Nasser.

Egypt, officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia by a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt is a Mediterranean country bordered by the Gaza Strip and Israel to the northeast, the Gulf of Aqaba and the Red Sea to the east, Sudan to the south, and Libya to the west. Across the Gulf of Aqaba lies Jordan, across the Red Sea lies Saudi Arabia, and across the Mediterranean lie Greece, Turkey and Cyprus, although none share a land border with Egypt.

In 1959, a piece of subordinate legislation was passed under the Foreign Compensation Act 1950 to distribute compensation paid by the Egyptian government to the UK government with respect to British properties it had nationalised. The appellants claimed that they were eligible for compensation under this piece of subordinate legislation, which was determined by a tribunal (the respondents in this case) set up under the Foreign Compensation Act 1950.

The tribunal, however, decided that the appellants were not eligible for compensation, because their "successors in title" (TEDO) did not have the British nationality as required under one of the provisions of the subordinate legislation.

There were two important issues on the appeal to the Court of Appeal and later, the House of Lords. The first was straightforward: whether the tribunal had made an error of law in construing the term "successor of title" under the subordinate legislation.

The House of Lords of the United Kingdom, in addition to having a legislative function, historically also had a judicial function. It functioned as a court of first instance for the trials of peers, for impeachment cases, and as a court of last resort within the United Kingdom. In the latter case the House's jurisdiction was essentially limited to the hearing of appeals from the lower courts. Appeals were technically not to the House of Lords, but rather to the Queen-in-Parliament. By constitutional convention, only those lords who were legally qualified heard the appeals, since World War II usually in what was known as the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords rather than in the chamber of the House.

The second issue was more complex and had important implications for the law on judicial review. Even if the tribunal had made an error of law, the House of Lords had to decide whether or not an appellate court had the jurisdiction to intervene in the tribunal's decision. Section 4(4) of the Foreign Compensation Act 1950 stated: “The determination by the commission of any application made to them under this Act shall not be called into question in any court of law”, this was a so-called "ouster clause".

An ouster clause or privative clause is, in countries with common law legal systems, a clause or provision included in a piece of legislation by a legislative body to exclude judicial review of acts and decisions of the executive by stripping the courts of their supervisory judicial function. According to the doctrine of the separation of powers, one of the important functions of the judiciary is to keep the executive in check by ensuring that its acts comply with the law, including, where applicable, the constitution. Ouster clauses prevent courts from carrying out this function, but may be justified on the ground that they preserve the powers of the executive and promote the finality of its acts and decisions.

The Asylum and Immigration Tribunal (AIT) was a tribunal constituted in the United Kingdom with jurisdiction to hear appeals from many immigration and asylum decisions. It was created on 4 April 2005, replacing the former Immigration Appellate Authority (IAA), and fell under the administration of the Tribunals Service.

An ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages these courts had much wider powers in many areas of Europe than before the development of nation states. They were experts in interpreting canon law, a basis of which was the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian which is considered the source of the civil law legal tradition.

The High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court in Scotland. The High Court is both a trial court and a court of appeal. As a trial court, the High Court sits on circuit at Parliament House or the former Sheriff Court building in Edinburgh, or in dedicated buildings in Glasgow and Aberdeen. The High Court sometimes sits in various smaller towns in Scotland, where it uses the local sheriff court building. As an appeal court the High Court sits only in Edinburgh.

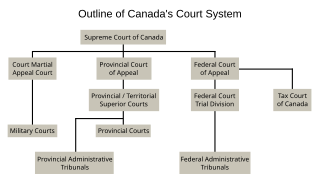

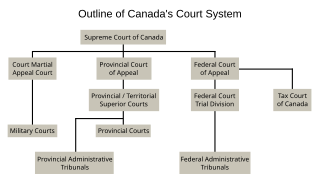

The court system of Canada forms the judicial branch of government, formally known as "The Queen on the Bench", which interprets the law and is made up of many courts differing in levels of legal superiority and separated by jurisdiction. Some of the courts are federal in nature, while others are provincial or territorial.

The courts of Scotland are responsible for administration of justice in Scotland, under statutory, common law and equitable provisions within Scots law. The courts are presided over by the judiciary of Scotland, who are the various judicial office holders responsible for issuing judgments, ensuring fair trials, and deciding on sentencing. The Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland, subject to appeals to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, and the High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court, which is only subject to the authority of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom on devolution issues and human rights compatibility issues.

Australian administrative law defines the extent of the powers and responsibilities held by administrative agencies of Australian governments. It is basically a common law system, with an increasing statutory overlay that has shifted its focus toward codified judicial review and to tribunals with extensive jurisdiction.

Northern Pipeline Construction Company v. Marathon Pipe Line Company, 458 U.S. 50 (1982), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that Article III jurisdiction could not be conferred on non-Article III courts.

The Land and Environment Court of New South Wales is a court within the Australian court hierarchy established pursuant to the Land and Environment Court Act 1979 (NSW) to hear environmental, development, building and planning disputes. The Court’s jurisdiction, confined to the state of New South Wales, Australia, includes merits review, judicial review, civil enforcement, criminal prosecution, criminal appeals and civil claims about planning, environmental, land, mining and other legislation.

Canadian administrative law is the body of law that addresses the actions and operations of governments and governmental agencies in Canada. That is, the law concerns the manner in which courts can review the decisions of administrative decision-makers (ADMs) such as a board, tribunal, commission, agency or Crown minister, when he or she exercises ministerial discretion.

Crevier v Quebec (AG), [1981] 2 S.C.R. 220 is a leading Supreme Court of Canada decision in administrative law. The court had to decide whether a Quebec-created Professionals Tribunal was unconstitutional due to being a "s. 96 court" according to the Constitution Act, 1867, whose members can only be federally appointed. It found that any legislation which has a privative clause purporting to exclude review of jurisdictional matters is outside the jurisdiction of a provincial legislature.

Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth, was a significant Australian court case, decided in the High Court of Australia on 4 February 2003. The case was an influential decision not only in relation to immigration law but to administrative law generally and is an authority for the proposition that Parliament cannot restrict the availability of constitutional writs.

Chng Suan Tze v. Minister for Home Affairs is a seminal case in administrative law decided by the Court of Appeal of Singapore in 1988. The Court decided the appeal in the appellants' favour on a technical ground, but considered obiter dicta the reviewability of government power in preventive detention cases under the Internal Security Act ("ISA"). The case approved the application by the court of an objective test in the review of government discretion under the ISA, stating that all power has legal limits and the rule of law demands that the courts should be able to examine the exercise of discretionary power. This was a landmark shift from the position in the 1971 High Court decision Lee Mau Seng v. Minister of Home Affairs, which had been an authority for the application of a subjective test until it was overruled by Chng Suan Tze.

Errors as to precedent facts, sometimes called jurisdictional facts, in Singapore administrative law are errors committed by public authorities concerning facts that must objectively exist or not exist before the authorities have the power to take actions or make decisions under legislation. If an error concerning a precedent fact is made, the statutory power has not been exercised lawfully and may be quashed by the High Court if judicial review is applied for by an aggrieved person. The willingness of the Court to review such errors of fact is an exception to the general rule that the Court only reviews errors of law.

Administrative law in Singapore is a branch of public law that is concerned with the control of governmental powers as exercised through its various administrative agencies. Administrative law requires administrators – ministers, civil servants and public authorities – to act fairly, reasonably and in accordance with the law. Singapore administrative law is largely based on English administrative law, which the nation inherited at independence in 1965.

Illegality is one of the three broad headings of judicial review of administrative action in Singapore, the others being irrationality and procedural impropriety. To avoid acting illegally, an administrative body or public authority must correctly understand the law regulating its power to act and to make decisions, and give effect to it.

Exclusion of judicial review has been attempted by the Parliament of Singapore to protect the exercise of executive power. Typically, this has been done though the insertion of finality or total ouster clauses into Acts of Parliament, or by wording powers conferred by Acts on decision-makers subjectively. Finality clauses are generally viewed restrictively by courts in the United Kingdom. The courts there have taken the view that such clauses are, subject to some exceptions, not effective in denying or restricting the extent to which the courts are able to exercise judicial review. In contrast, Singapore cases suggest that ouster clauses cannot prevent the High Court from exercising supervisory jurisdiction over the exercise of executive power where authorities have committed jurisdictional errors of law, but are effective against non-jurisdictional errors of law.

Jurisdictional Fact is a concept in Administrative Law.

It is a set of circumstances set out in a statute that must exist before a government official can act. They are created by and operate in the context of government authority produced by statute and are linked to the legal concept of Jurisdiction. A number of scholars have tried with limited success to categorise them.

In Canada, judicial review is the process that allows courts to supervise administrative tribunals' exercise of their statutory powers. Judicial review of administrative action is only available for decisions made by a governmental or quasi-governmental authority. The process allows individuals to challenge state actions, and ensures that decisions made by administrative tribunals follow the rule of law. The practice is meant to ensure that powers delegated by government to boards and tribunals are not abused, and offers legal recourse when that power is misused, or the law is misapplied. Judicial review is meant to be a last resort for those seeking to redress a decision of an administrative decision maker.