| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Jain law or Jaina law is the modern interpretation of ancient Jain law that consists of rules for adoption, marriage, succession and death prescribed for the followers of Jainism.

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Jain law or Jaina law is the modern interpretation of ancient Jain law that consists of rules for adoption, marriage, succession and death prescribed for the followers of Jainism.

Jains regard Bharata Chakravartin as the first law giver of the present half cycle of time. [1] Jains have their own law books. Vardhamana Niti and Ashana Niti by the great Jain teacher Hemachandra deals with Jain law. [2] Bhadrabahu Samhit is also considered an important book on Jaina law.

In 1916, Barrister Jagomandar Lal Jaini (1881-1927) published a translation of Bhadrabahu Samhita, which went on to form the basis of modern Jain law. The author mentioned the full text of a judgement that he delivered in Civil Original Case No. 6 of 1914, Indore, in which Jain religious and legal scriptures were explicitly quoted and relied upon. [3] It has been suggested that Jain mendicants kept Jain lawbooks away from the British because of the Jain laws of purity. [4] Jain lawgivers had taken great pains to define violence, and were clear that no form of violence was permitted for Jain mendicants. The lawgivers were not so clear on the conduct of Jain laymen, assuming that a violent situation would not arise amongst a community that was numerically small. [4]

After the Montagu Declaration in 1917, the Jain Political Association was set up by the same circle of predominantly Digambara Jain intellectuals to create a unitary political representation for the Jains. In due course the society intended, after due search of the śāstric literature, to give a definite shape to Jaina Law. [5] The culmination of this effort was the most prominent book on the subject of Jain law, written by Champat Rai Jain. [6]

In 1955, the Government of India subsumed Jain law under Hindu law, though Jain law continues in unofficial and semi-official fora. [7]

In 1927, Madras High Court in Gateppa v. Eramma and others reported in AIR 1927 Madras 228, the court held that in Bhadrabahu Samhita, verse 40 empowers a sonless man or woman to take a boy in adoption. Verse 83 empowers a widow to adopt a boy and make over her property to him. Verse 73 was quoted in the judgement [8] -

The virtuous lady may like her husband take to herself a son of a good gotra and instal him on the estate of her husband.

Jain Agamas mention that there are five types of marriages. [9]

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

The rights of female heir in Jaina law are different from that of Hindu Law. Under the Jaina Law females take the inheritance absolutely. [10]

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

Upon the death of a person without a son, the property is entirely passed on to the widow. The property remains with the widow even if there were to be a son. This is an important difference between Jain law and Hindu law. In Hindu law, the widow does not have the right to the deceased husband's property. In Jainism, there is no privilege accorded to a male heir, and a widow is treated as a preferential heir to her own son. [11]

According to Jain law, in case of twin born sons, the first born or the eldest is entitled for more privileges at the time of partition. [1]

Jainism, also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras, with the first in the current time cycle being Rishabhadeva, whom the tradition holds to have lived millions of years ago, the twenty-third tirthankara Parshvanatha, whom historians date to the 9th century BCE, and the twenty-fourth tirthankara Mahavira, around 600 BCE. Jainism is considered an eternal dharma with the tirthankaras guiding every time cycle of the cosmology. Central to understanding Jain philosophy is the concept of bhedvigyān, or the clear distinction in the nature of the soul and non-soul entities. This principle underscores the innate purity and potential for liberation within every soul, distinct from the physical and mental elements that bind it to the cycle of birth and rebirth. Recognizing and internalizing this separation is essential for spiritual progress and the attainment of samyak darshan or self realization, which marks the beginning of the aspirant's journey towards liberation. The three main pillars of Jainism are ahiṃsā (non-violence), anekāntavāda (non-absolutism), and aparigraha (asceticism).

Civaka Cintamani, also spelled as Jivaka Chintamani, is one of the five great Tamil epics. Authored by a Madurai-based Jain ascetic Tiruttakkatēvar in the early 10th century, the epic is a story of a prince who is the perfect master of all arts, perfect warrior and perfect lover with numerous wives. The Civaka Cintamani is also called the Mana Nool. The epic is organized into 13 cantos and contains 3,145 quatrains in viruttam poetic meter. Its Jain author is credited with 2,700 of these quatrains, the rest by his guru and another anonymous author.

In Jainism, a Tirthankara is a saviour and supreme preacher of the dharma. The word tirthankara signifies the founder of a tirtha, a fordable passage across saṃsāra, the sea of interminable birth and death. According to Jains, tirthankaras are the supreme preachers of dharma, who have conquered saṃsāra on their own and made a path for others to follow. After understanding the true nature of the self or soul, the Tīrthaṅkara attains kevala jnana (omniscience). A Tirthankara provides a bridge for others to follow them from saṃsāra to moksha (liberation).

Ādi purāṇa is a 9th-century CE Sanskrit poem composed by Jinasena, a Digambara monk. It deals with the life of Rishabhanatha, the first Tirthankara.

Bahubali was the son of Rishabhanatha and the brother of the chakravartin Bharata. He is a revered figure in Jainism. He is said to have meditated motionless for 12 years in a standing posture (kayotsarga), with climbing plants having grown around his legs. After his 12 years of meditation, he is said to have attained omniscience.

Sallekhana, also known as samlehna, santhara, samadhi-marana or sanyasana-marana, is a supplementary vow to the ethical code of conduct of Jainism. It is the religious practice of voluntarily fasting to death by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids. It is viewed in Jainism as the thinning of human passions and the body, and another means of destroying rebirth-influencing karma by withdrawing all physical and mental activities. It is not considered a suicide by Jain scholars because it is not an act of passion, nor does it employ poisons or weapons. After the sallekhana vow, the ritual preparation and practice can extend into years.

Rishabhanatha, also Rishabhadeva, Rishabha or Ikshvaku, is the first tirthankara of Jainism. He was the first of twenty-four teachers in the present half-cycle of time in Jain cosmology, and called a "ford maker" because his teachings helped one cross the sea of interminable rebirths and deaths. The legends depict him as having lived millions of years ago. He was the spiritual successor of Sampratti Bhagwan, the last Tirthankara of the previous time cycle. He is also known as Ādinātha, as well as Adishvara, Yugadideva, Prathamarajeshwara and Nabheya. He is also known as Ikshvaku, establisher of the Ikshvaku dynasty. Along with Mahavira, Parshvanath, Neminath, and Shantinath, Rishabhanatha is one of the five Tirthankaras that attract the most devotional worship among the Jains.

Jain meditation has been the central practice of spirituality in Jainism along with the Three Jewels. Jainism holds that emancipation can only be achieved through meditation or shukla dhyana. According to Sagarmal Jain, it aims to reach and remain in a state of "pure-self awareness or knowership." Meditation is also seen as realizing the self, taking the soul to complete freedom, beyond any craving, aversion and/or attachment. The 20th century saw the development and spread of new modernist forms of Jain Dhyana, mainly by monks and laypersons of Śvētāmbara Jainism.

King Nabhi or Nabhi Rai was the 14th or the last Kulakara of avasarpini. He was the father of Rishabhanatha, the first tirthankara of present avasarpini. According to Jain text Ādi purāṇa, Nabhirāja lived for 1 crore purva and his height was 525 dhanusha.

Jainism is a religion founded in ancient India. Jains trace their history through twenty-four tirthankara and revere Rishabhanatha as the first tirthankara. The last two tirthankara, the 23rd tirthankara Parshvanatha and the 24th tirthankara Mahavira are considered historical figures. According to Jain texts, the 22nd tirthankara Neminatha lived about 84,000 years ago and was the cousin of Krishna.

Jain literature refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

Michchhāmi Dukkaḍaṃ, also written as michchha mi dukkadam, is an ancient Indian Prakrit language phrase, found in historic Jain texts. Its Sanskrit equivalent is "Mithya me duskrtam" and both literally mean "may all the evil that has been done be in vain".

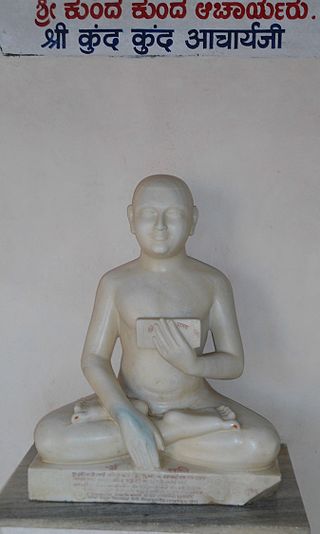

Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra is a Jain text composed by Aacharya Samantbhadra Swamy, an acharya of the Digambara sect of Jainism. Aacharya Samantbhadra Swamy was originally from Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu. Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra is the earliest and one of the best-known śrāvakācāra.

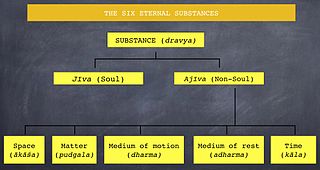

Dravya means substance or entity. According to the Jain philosophy, the universe is made up of six eternal substances: sentient beings or souls (jīva), non-sentient substance or matter (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), the principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla). The latter five are united as the ajiva. As per the Sanskrit etymology, dravya means substances or entity, but it may also mean real or fundamental categories.

Digambara is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvetāmbara (white-clad). The Sanskrit word Digambara means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing nor wearing any clothes.

Jainism and Hinduism are two ancient Indian religions. There are some similarities and differences between the two religions. Temples, gods, rituals, fasts and other religious components of Jainism are different from those of Hinduism.

In Jainism, Bharata was the first chakravartin of the Avasarpini. He was the eldest son of Rishabhanatha, the first tirthankara. He had two sons from his chief-empress Subhadra, named Arkakirti and Marichi. He is said to have conquered all six parts of the world and to have engaged in a fight with Bahubali, his brother, to conquer the last remaining city of the world.

Champat Rai Jain was a Digambara Jain born in Delhi and who studied and practised law in England. He became an influential Jainism scholar and comparative religion writer between 1910s and 1930s who translated and interpreted Digambara texts. In early 1920s, he became religiously active in India and published essays and articles defending Jainism against misrepresentations by colonial era Christian missionaries, contrasting Jainism and Christianity. He founded Akhil Bharatvarsiya Digambara Jain Parisad in 1923 with the aim of activist reforms and uniting the south Indian and north Indian Digambara community. He visited various European countries to give lectures on Jainism. He was conferred with the title Vidya-Varidhi by Bharata Dharma Mahamandal.

Aryika, also known as Sadhvi, is a female mendicant (nun) in Jainism.

Aptamimamsa is a Jain text composed by Acharya Samantabhadra, a Jain acharya said to have lived about the latter part of the second century AD. Āptamīmāṁsā is a treatise of 114 verses which discusses the Jaina view of Reality, starting with the concept of omniscience and the attributes of the Omniscient.