According to various Indian schools of philosophy, tattvas are the elements or aspects of reality that constitute human experience. In some traditions, they are conceived as an aspect of deity. Although the number of tattvas varies depending on the philosophical school, together they are thought to form the basis of all our experience. The Samkhya philosophy uses a system of 25 tattvas, while Shaivism recognises 36 tattvas. In Buddhism, the equivalent is the list of dhammas which constitute reality, as in Nama-rupa.

In Indian philosophy and some Indian religions, samskaras or sanskaras are mental impressions, recollections, or psychological imprints. In Hindu philosophies, samskaras are a basis for the development of karma theory.

Tattvārthasūtra, meaning "On the Nature [artha] of Reality [tattva]" is an ancient Jain text written by Acharya Umaswami in Sanskrit, sometime between the 2nd- and 5th-century CE.

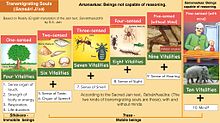

Karma is the basic principle within an overarching psycho-cosmology in Jainism. Human moral actions form the basis of the transmigration of the soul. The soul is constrained to a cycle of rebirth, trapped within the temporal world, until it finally achieves liberation. Liberation is achieved by following a path of purification.

Samayasāra is a famous Jain text composed by Acharya Kundakunda in 439 verses. Its ten chapters discuss the nature of Jīva, its attachment to Karma and Moksha (liberation). Samayasāra expounds the Jain concepts like Karma, Asrava, Bandha (Bondage), Samvara (stoppage), Nirjara (shedding) and Moksha.

In Jainism, ahiṃsā is a fundamental principle forming the cornerstone of its ethics and doctrine. The term ahiṃsā means nonviolence, non-injury, and absence of desire to harm any life forms. Veganism, vegetarianism and other nonviolent practices and rituals of Jains flow from the principle of ahimsa. There are five specific transgressions of Ahimsa principle in Jain scriptures – binding of animals, beating, mutilating limbs, overloading, withholding food and drink. Any other interpretation is subject to individual choices and not authorized by scriptures.

Nirjara is one of the seven fundamental principles, or Tattva in Jain philosophy, and refers to the shedding or removal of accumulated karmas from the atma (soul), essential for breaking free from samsara, the cycle of birth-death and rebirth, by achieving moksha, liberation.

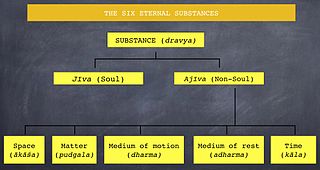

Jain philosophy or Jaina philosophy refers to the ancient Indian philosophical system of the Jain religion. It comprises all the philosophical investigations and systems of inquiry that developed among the early branches of Jainism in ancient India following the parinirvāṇa of Mahāvīra. One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence: the living, conscious, or sentient beings (jīva) and the non-living or material entities (ajīva).

Sanskrit moksha or Prakrit mokkha refers to the liberation or salvation of a soul from saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death. It is a blissful state of existence of a soul, attained after the destruction of all karmic bonds. A liberated soul is said to have attained its true and pristine nature of infinite bliss, infinite knowledge and infinite perception. Such a soul is called siddha and is revered in Jainism.

Jainism emphasises that ratnatraya — the right faith, right knowledge and right conduct — constitutes the path to liberation. These are known as the triple gems of Jainism and hence also known as Ratnatraya

Jain philosophy explains that seven tattva constitute reality. These are:—

- jīva- the soul which is characterized by consciousness

- ajīva- the non-soul

- āsrava (influx)- inflow of auspicious and evil karmic matter into the soul.

- bandha (bondage)- mutual intermingling of the soul and karmas.

- samvara (stoppage)- obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul.

- nirjara - separation or falling-off of part of karmic matter from the soul.

- mokṣha (liberation)- complete annihilation of all karmic matter.

The karmic process in Jainism is based on seven truths or fundamental principles (tattva) of Jainism which explain the human predicament. Out of those, four—influx (āsrava), bondage (bandha), stoppage (saṃvara) and release (nirjarā)—pertain to the karmic process. Karma gets bound to the soul on account of two processes:

Asrava is one of the tattva or the fundamental reality of the world as per the Jain philosophy. It refers to the influence of body and mind causing the soul to generate karma.

Samvara (saṃvara) is one of the tattva or the fundamental reality of the world as per the Jain philosophy. It means stoppage—the stoppage of the influx of the material karmas into the soul consciousness. The karmic process in Jainism is based on seven truths or fundamental principles (tattva) of Jainism which explain the human predicament. Out of the seven, the four influxes (āsrava), bondage (bandha), stoppage (saṃvara) and release (nirjarā)—pertain to the karmic process.

Jīva or Ātman is a philosophical term used within Jainism to identify the soul. As per Jain cosmology, jīva or soul is the principle of sentience and is one of the tattvas or one of the fundamental substances forming part of the universe. The Jain metaphysics, states Jagmanderlal Jaini, divides the universe into two independent, everlasting, co-existing and uncreated categories called the jiva (soul) and the ajiva. This basic premise of Jainism makes it a dualistic philosophy. The jiva, according to Jainism, is an essential part of how the process of karma, rebirth and the process of liberation from rebirth works.

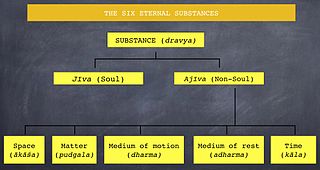

Dravya means substance or entity. According to the Jain philosophy, the universe is made up of six eternal substances: sentient beings or souls (jīva), non-sentient substance or matter (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), the principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla). The latter five are united as the ajiva. As per the Sanskrit etymology, dravya means substances or entity, but it may also mean real or fundamental categories.

Dravyasaṃgraha is a 10th-century Jain text in Jain Sauraseni Prakrit by Acharya Nemicandra belonging to the Digambara Jain tradition. It is a composition of 58 gathas (verses) giving an exposition of the six dravyas (substances) that characterize the Jain view of the world: sentient (jīva), non-sentient (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla). It is one of the most important Jain works and has gained widespread popularity. Dravyasaṃgraha has played an important role in Jain education and is often memorized because of its comprehensiveness as well as brevity.

Self-realization is a term used in western psychology, philosophy, and spirituality; and in eastern Indian religions. In the western understanding, it is the "fulfillment by oneself of the possibilities of one's character or personality". In the Indian understanding, self-realization is liberating knowledge of the true Self, either as the permanent undying Purusha or witness-consciousness, which is atman (essence), or as the absence (sunyata) of such a permanent Self.

Umaswati, also spelled as Umasvati and known as Umaswami, was an Indian scholar, possibly between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE, known for his foundational writings on Jainism. He authored the Jain text Tattvartha Sutra. Umaswati's work was the first Sanskrit language text on Jain philosophy, and is the earliest extant comprehensive Jain philosophy text accepted as authoritative by all four Jain traditions. His text has the same importance in Jainism as Vedanta Sutras and Yogasutras have in Hinduism.

In Jain tradition, twelve contemplations, are the twelve mental reflections that a Jain ascetic and a practitioner should repeatedly engage in. These twelve contemplations are also known as Barah anuprekśa or Barah bhāvana. According to Jain Philosophy, these twelve contemplations pertain to eternal truths like nature of universe, human existence, and karma on which one must meditate. Twelve contemplations is an important topic that has been developed at all epochs of Jain literature. They are regarded as summarising fundamental teachings of the doctrine. Stoppage of new Karma is called Samvara. Constant engagement on these twelve contemplations help the soul in samvara or stoppage of karmas.