Congregational polity, or congregationalist polity, often known as congregationalism, is a system of ecclesiastical polity in which every local church (congregation) is independent, ecclesiastically sovereign, or "autonomous". Its first articulation in writing is the Cambridge Platform of 1648 in New England.

Evangelicalism, also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that puts primary emphasis on evangelization. The word evangelic comes from the Greek word for 'good news'. The Gospel story of the salvation from sin is considered "the good news". The process of personal conversion involves complete surrender to Jesus Christ. The conversion process is authoritatively guided by the Bible, the God in Christianity's revelation to humanity. Critics of the conceptualization of evangelicalism, argue that it is too broad, too diverse, or too ill-defined to be adequately seen as a movement or a single movement.

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement that emphasizes direct personal experience of God through baptism with the Holy Spirit. The term Pentecostal is derived from Pentecost, an event that commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers of Jesus Christ while they were in Jerusalem celebrating the Feast of Weeks, as described in the Acts of the Apostles.

Restorationism, also known as Restitutionism or Christian primitivism, is a religious perspective according to which the early beliefs and practices of the followers of Jesus were either lost or adulterated after his death and required a "restoration". It is a view that often "seeks to correct faults or deficiencies, in other branches of Christianity, by appealing to the primitive church as normative model".

A megachurch is a church with a very large membership that also offers a variety of educational and social activities. Most megachurches are Protestant, and particularly Evangelical, although the word denotes a type of organization, not a denomination. The Hartford Institute for Religion Research defines a megachurch as any Protestant Christian church that draws 2,000 or more people in a weekend.

A Christian denomination is a distinct religious body within Christianity that comprises all church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadership, theological doctrine, worship style and, sometimes, a founder. It is a secular and neutral term, generally used to denote any established Christian church. Unlike a cult or sect, a denomination is usually seen as part of the Christian religious mainstream. Most Christian denominations refer to themselves as churches, whereas some newer ones tend to interchangeably use the terms churches, assemblies, fellowships, etc. Divisions between one group and another are defined by authority and doctrine; issues such as the nature of Jesus, the authority of apostolic succession, biblical hermeneutics, theology, ecclesiology, eschatology, and papal primacy may separate one denomination from another. Groups of denominations—often sharing broadly similar beliefs, practices, and historical ties—are sometimes known as "branches of Christianity". These branches differ in many ways, especially through differences in practices and belief.

The charismatic movement in Christianity is a movement within established or mainstream Christian denominations to adopt beliefs and practices of Charismatic Christianity, with an emphasis on baptism with the Holy Spirit, and the use of spiritual gifts (charismata). It has affected most denominations in the United States, and has spread widely across the world.

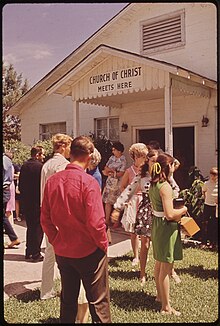

The group of churches known as the Christian Churches and Churches of Christ is a fellowship of congregations within the Restoration Movement that have no formal denominational affiliation with other congregations, but still share many characteristics of belief and worship. Churches in this tradition are strongly congregationalist and have no formal denominational ties, and thus there is no proper name that is agreed upon and applied to the movement as a whole. Most congregations in this tradition include the words "Christian Church" or "Church of Christ" in their congregational name. Due to the lack of formal organization between congregations, there is a lack of official statistical data, but the 2016 Directory of the Ministry documents some 5000 congregations in the US and Canada; some estimate the number to be over 6,000 since this directory is unofficial. By 1988, the movement had 1,071,616 members in the United States.

The mainline Protestant churches are a group of Protestant denominations in the United States and Canada largely of the theologically liberal or theologically progressive persuasion that contrast in history and practice with the largely theologically conservative evangelical, fundamentalist, charismatic, confessional, Confessing Movement, historically Black church, and Global South Protestant denominations and congregations. Some make a distinction between "mainline" and "oldline", with the former referring only to denominational ties and the latter referring to church lineage, prestige and influence. However, this distinction has largely been lost to history and the terms are now nearly synonymous.

A united church, also called a uniting church, is a denomination formed from the merger or other form of church union of two or more different Protestant Christian denominations, a number of which come from separate and distinct denominational orientations or traditions. Multi-denominationalism, or a multi-denominational church or organization, is a congregation or organization that is affiliated with two or more Christian denominations, whether they be part of the same tradition or from separate and distinct traditions.

The Neo-charismaticmovement is a movement within evangelical Protestant Christianity that is composed of a diverse range of independent churches and organizations that emphasize the current availability of gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as speaking in tongues and faith healing. The Neo-charismatic movement is considered to be the "third wave" of the Charismatic Christian tradition which began with Pentecostalism, and was furthered by the Charismatic movement. As a result of the growth of postdenominational and independent charismatic groups, Neo-charismatics are now believed to be more numerous than the first and second wave categories. As of 2002, some 19,000 denominations or groups, with approximately 295 million individual adherents, were identified as Neo-charismatic.

Protestant denominations arrived in the Philippines in 1898, after the United States took control of the Philippines from Spain, first with United States Army chaplains and then within months civilian missionaries.

The Evangelical Christian Church(Christian Disciples) as an evangelical Protestant Canadian church body. The Evangelical Christian Church's national office in Canada is in Waterloo, Ontario.

Christianity is the most prevalent religion in the United States. Estimates from 2021 suggest that of the entire U.S. population about 63% is Christian. The majority of Christian Americans are Protestant Christians, though there are also significant numbers of American Roman Catholics and other Christian denominations such as Latter Day Saints, Eastern Orthodox Christians and Oriental Orthodox Christians, and Jehovah's Witnesses. The United States has the largest Christian population in the world and, more specifically, the largest Protestant population in the world, with nearly 210 million Christians and, as of 2021, over 140 million people affiliated with Protestant churches, although other countries have higher percentages of Christians among their populations. The Public Religion Research Institute's "2020 Census of American Religion", carried out between 2014 and 2020, showed that 70% of Americans identified as Christian during this seven-year interval. In a 2020 survey by the Pew Research Center, 65% of adults in the United States identified themselves as Christians. They were 75% in 2015, 70.6% in 2014, 78% in 2012, 81.6% in 2001, and 85% in 1990. About 62% of those polled claim to be members of a church congregation.

Protestantism is the largest grouping of Christians in the United States, with its combined denominations collectively comprising about 43% of the country's population in 2019. Other estimates suggest that 48.5% of the U.S. population is Protestant. Simultaneously, this corresponds to around 20% of the world's total Protestant population. The U.S. contains the largest Protestant population of any country in the world. Baptists comprise about one-third of American Protestants. The Southern Baptist Convention is the largest single Protestant denomination in the U.S., comprising one-tenth of American Protestants. Twelve of the original Thirteen Colonies were Protestant, with only Maryland having a sizable Catholic population due to Lord Baltimore's religious tolerance.

Pentecostalism in Australia is a large and growing Christian movement. Pentecostalism is a renewal movement within Protestant Christianity that places special emphasis on a direct personal experience of God through baptism with the Holy Spirit. It emerged from 19th century precursors between 1870 and 1910, taking denominational form from c. 1927. From the early 1930s, Pentecostal denominations multiplied, and there are now several dozen, the largest of which relate to one another through conferences and organisations such as the Australian Pentecostal Ministers Fellowship. The Australian Christian Churches, formerly known as the Australian Assemblies of God, is the oldest and longest lasting Pentecostal organisation in Australia. The AOG/ACC is also the largest Pentecostal organisation in Australia with over 300,000 members in 2018. Until 2018, Hillsong Church was one of 10 megachurches in Australia associated with the ACC that have at least 2,000 members weekly. According to the church, over 100,000 people attend services each week at the church or one of its 80 affiliated churches located worldwide.

Charismatic Christianity is a form of Christianity that emphasizes the work of the Holy Spirit and spiritual gifts as an everyday part of a believer's life. It has a global presence in the Christian community. Practitioners are often called charismatic Christians or renewalists. Although there is considerable overlap, charismatic Christianity is often categorized into three separate groups: Pentecostalism, the Charismatic movement, and the neo-charismatic movement.

Evangelical theology is the teaching and doctrine that relates to spiritual matters in evangelical Christianity and a Christian theology. The main points concern the place of the Bible, the Trinity, worship, salvation, sanctification, charity, evangelism and the end of time.