Terminology

Neurotheology

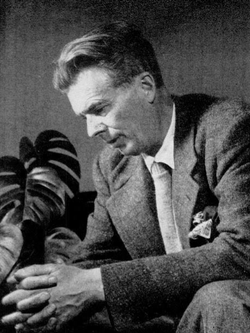

Aldous Huxley coined the term "neurotheology" for the first time[ citation needed ] in his utopian novel Island . [5] In this, he described the discipline as a combination of cognitive neuroscience of religious experience and spirituality. The term has also been used in a less scientific context, as a subcategory of philosophy. In some cases, according to the mainstream scientific community, it is considered a pseudoscience.

Biocultural

In Armin W. Geertz article on Brain, Body and Culture: A Biocultural Theory of Religion, the term "biocultural" refers to the simultaneous intersection of humans as both biological and cultural animals. [6] In his article, Geertz discusses the connection between the human brain and the rest of the body, stating that the brain does not work independently, but rather in unison with other sense organs in the body. Essentially, arguing that the "cognition functions in the embodiment of the brain." [7] With this, he says that religio-spiritual practices (such as dancing, chanting, or the use of psychoactive substances) that engage the other senses, have physical effects on brain chemistry. This varies cross-culturally, as different cultural and religious practices engage in different methods to induce senses of divine transcendence. This, in turn, demonstrates the connection between biology and cultural contexts, since neither are uniform.

Religion

Spiritual practices and religious rituals have been around for hundreds of thousands of years with some dating as far back as 300,000 in the Rising Star Cave with the discovery of Homo Naledi. Dave Vliegenthart's article Can Neurotheology Explain Religion? aims at answering the question of neurotheology as a legitimate way of explaining religious experiences. In this he defines the term "religion" as a "state of consciousness in which reality is deemed religious and thought and experienced through the lens of a particular human mind-set." [8] This is categorized under feelings of intuition, higher or altered states of consciousness, or a connection to a divine being. Through attempts to achieve religious ecstasy, people have tried to connect to divine or ethereal beings as a way to breed human connection in addition to achieving higher wisdom. This goal of attaining eternal knowledge or harmony with the universe is demonstrated cross culturally, as mentioned above in Geertz's work on biocultural studies.

Consciousness

According to an article in Scientific American , "consciousness" is everything a person experiences: a personal sense of reality based on experiences of one's own real life events. [9] The article discusses the neuronal correlates of consciousness and the neurological process that go behind the brain's formations of conscious thinking, saying how the senses relay information through the spinal cord to the cerebellum in order to translate physical experience into neurological interpretation. [9] For hundreds of thousands of years humans have been trying to find ways to alter their states of consciousness. This varies widely across cultural groups, religious practices, and more so when looking from individual to individual. In Ancient Greece, maenads would attempt this by ecstatic and frenzied dance. In Sufi Mysticism, also known as Rumism, there is a similar practice of the whirling dervishes where spinning in circles to music is done in order to create a connection with the Divine. In some more extreme cases, it may include forms of asceticism such as fasting, celibacy, or extreme isolation.