Empirical studies

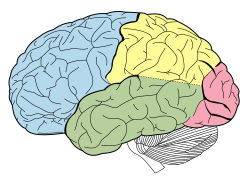

The empirical study of mysticism today focuses on two topics: identifying the neurological correlates of mystical experiences, and demonstrating the purported benefits of meditation. [131] Correlates between mystical experiences and neurological activity have been established, pointing to the temporal lobe as the main locus for these experiences, while Andrew B. Newberg and Eugene G. d'Aquili have also pointed to the parietal lobe. Recent research points to the relevance of the default mode network [11] and the anterior insula, which may be related to the experience of ineffability, the subjective sense of certainty induced by mystical experiences. [12] [13] [14]

Neuroscience

| Lobes of the human brain |

|---|

| Lobes of the human brain (temporal lobe is shown in green) |

Early studies in the 1950s and 1960s attempted to use EEGs to study brain wave patterns correlated with spiritual states. During the 1980s Dr. Michael Persinger stimulated the temporal lobes of human subjects with a weak magnetic field. [132] His subjects claimed to have a sensation of "an ethereal presence in the room." [133] Some current studies use neuroimaging to localize brain regions active, or differentially active, during religious experiences. [134] [135] These neuroimaging studies have implicated a number of brain regions, including the limbic system, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior parietal lobe, and caudate nucleus. [136] [137] [138] Based on the complex nature of religious experience, it is likely that they are mediated by an interaction of neural mechanisms that all add a small piece to the overall experience. [137]

Neuroscience of religion, also known as neurotheology, biotheology or spiritual neuroscience, [139] is the study of correlations of neural phenomena with subjective experiences of spirituality and hypotheses to explain these phenomena. Proponents of neurotheology claim that there is a neurological and evolutionary basis for subjective experiences traditionally categorized as spiritual or religious. [140]

The neuroscience of religion takes neural correlates as the basis of cognitive functions and religious experiences. These religious experiences are thereby emergent properties of neural correlates. This approach does not necessitate exclusion of the Self, but interprets the Self as influenced or otherwise acted upon by underlying neural mechanisms. Proponents argue that religious experience can be evoked through stimulus of specific brain regions and/or can be observed through measuring increase in activity of specific brain regions. [134] [note 23]

According to the neurotheologist Andrew B. Newberg and two colleagues, neurological processes which are driven by the repetitive, rhythmic stimulation which is typical of human ritual, and which contribute to the delivery of transcendental feelings of connection to a universal unity.[ clarification needed ] They posit, however, that physical stimulation alone is not sufficient to generate transcendental unitive experiences. For this to occur they say there must be a blending of the rhythmic stimulation with ideas. Once this occurs "...ritual turns a meaningful idea into a visceral experience." [143] Moreover, they say that humans are compelled to act out myths by the biological operations of the brain due to what they call the "inbuilt tendency of the brain to turn thoughts into actions."

An alternate approach is influenced by personalism, and exists contra-parallel to the reductionist approach. It focuses on the Self as the object of interest, [note 24] the same object of interest as in religion.[ citation needed ] According to Patrick McNamara, a proponent of personalism, the Self is a neural entity that controls rather than consists of the cognitive functions being processed in brain regions. [145] [146]

A biological basis for religious experience may exist. [146] [147] References to the supernatural or mythical beings first appeared approximately 40,000 years ago. [148] [149] A popular theory posits that dopaminergic brain systems are the evolutionary basis for human intellect [150] [149] and more specifically abstract reasoning. [149] The capacity for religious thought arises from the capability to employ abstract reasoning. There is no evidence to support the theory that abstract reasoning, generally or with regard to religious thought, evolved independent of the dopaminergic axis. [149] Religious behavior has been linked to "extrapersonal brain systems that predominate the ventromedial cortex and rely heavily on dopaminergic transmission." [149] A biphasic effect exists with regard to activation of the dopaminergic axis and/or ventromedial cortex. While mild activation can evoke a perceived understanding of the supernatural, extreme activation can lead to delusions characteristic of psychosis. [149] Stress can cause the depletion of 5-hydroxytryptamine, also referred to as serotonin. [151] The ventromedial 5-HT axis is involved in peripersonal activities such as emotional arousal, social skills, and visual feedback. [149] When 5-HT is decreased or depleted, one may become subject to "incorrect attributions of self-initiated or internally generated activity (e.g. hallucinations)." [152]

Temporal lobe

Temporal lobe epilepsy has become a popular field of study due to its correlation to religious experience. [153] [154] [155] [156] Religious experiences and hyperreligiosity are often used to characterize those with temporal lobe epilepsy. [157] [158] Visionary religious experiences, and momentary lapses of consciousness, may point toward a diagnosis of Geschwind syndrome. More generally, the symptoms are consistent with features of temporal lobe epilepsy, not an uncommon feature in religious icons and mystics. [159] It seems that this phenomenon is not exclusive to TLE, but can manifest in the presence of other epileptic variates [160] [161] [149] as well as mania, obsessive-compulsive disorder, [162] and schizophrenia, conditions characterized by ventromedial dopaminergic dysfunction. [149]

The temporal lobe generates the feeling of "I", and gives a feeling of familiarity or strangeness to the perceptions of the senses. [web 5] It seems to be involved in mystical experiences, [web 5] [12] and in the change in personality that may result from such experiences. [web 5] There is a long-standing notion that epilepsy and religion are linked, [158] and some religious figures may have had temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Raymond Bucke's book Cosmic Consciousness (1901) contains several case-studies of persons who have realized "cosmic consciousness"; [web 5] several of these cases are also being mentioned in J.E. Bryant's 1953 book, Genius and Epilepsy, which has a list of more than 20 people that combines the great and the mystical. [163] James Leuba's The psychology of religious mysticism noted that "among the dread diseases that afflict humanity there is only one that interests us quite particularly; that disease is epilepsy." [164] [158]

Slater and Beard renewed the interest in TLE and religious experience in the 1960s. [165] Dewhurst and Beard (1970) described six cases of TLE-patients who underwent sudden religious conversions. They placed these cases in the context of several western saints with a sudden conversion, who were or may have been epileptic. Dewhurst and Beard described several aspects of conversion experiences, and did not favor one specific mechanism. [158]

Norman Geschwind described behavioral changes related to temporal lobe epilepsy in the 1970s and 1980s. [166] Geschwind described cases which included extreme religiosity, now called Geschwind syndrome , [166] and aspects of the syndrome have been identified in some religious figures, in particular extreme religiosity and hypergraphia (excessive writing). [166] Geschwind introduced this "interictal personality disorder" to neurology, describing a cluster of specific personality characteristics which he found characteristic of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Critics note that these characteristics can be the result of any illness, and are not sufficiently descriptive for patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. [web 6]

Neuropsychiatrist Peter Fenwick, in the 1980s and 1990s, also found a relationship between the right temporal lobe and mystical experience, but also found that pathology or brain damage is only one of many possible causal mechanisms for these experiences. He questioned the earlier accounts of religious figures with temporal lobe epilepsy, noticing that "very few true examples of the ecstatic aura and the temporal lobe seizure had been reported in the world scientific literature prior to 1980". According to Fenwick, "It is likely that the earlier accounts of temporal lobe epilepsy and temporal lobe pathology and the relation to mystic and religious states owes more to the enthusiasm of their authors than to a true scientific understanding of the nature of temporal lobe functioning." [web 7]

The occurrence of intense religious feelings in epileptic patients in general is rare, [web 5] with an incident rate of about 2–3%. Sudden religious conversion, together with visions, has been documented in only a small number of individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy. [167] The occurrence of religious experiences in TLE-patients may as well be explained by religious attribution, due to the background of these patients. [165] Nevertheless, the Neuroscience of religion is a growing field of research, searching for specific neurological explanations of mystical experiences. Those rare epileptic patients with ecstatic seizures may provide clues for the neurological mechanisms involved in mystical experiences, such as the anterior insular cortex, which is involved in self-awareness and subjective certainty. [12] [168] [13] [14]

Anterior insula

A common quality in mystical experiences is ineffability, a strong feeling of certainty which cannot be expressed in words. This ineffability has been threatened with scepticism. According to Arthur Schopenhauer the inner experience of mysticism is philosophically unconvincing. [169] [note 25] In The Emotion Machine , Marvin Minsky argues that mystical experiences only seem profound and persuasive because the mind's critical faculties are relatively inactive during them. [170] [note 27]

Geschwind and Picard propose a neurological explanation for this subjective certainty, based on clinical research of epilepsy. [12] [13] [14] [note 28] According to Picard, this feeling of certainty may be caused by a dysfunction of the anterior insula, a part of the brain which is involved in interoception, self-reflection, and in avoiding uncertainty about the internal representations of the world by "anticipation of resolution of uncertainty or risk". This avoidance of uncertainty functions through the comparison between predicted states and actual states, that is, "signaling that we do not understand, i.e., that there is ambiguity." [172] Picard notes that "the concept of insight is very close to that of certainty," and refers to Archimedes "Eureka!" [173] [note 29] Picard hypothesizes that in ecstatic seizures the comparison between predicted states and actual states no longer functions, and that mismatches between predicted state and actual state are no longer processed, "block[ing] negative emotions and negative arousal arising from predictive uncertainty," which will be experienced as emotional confidence. [174] [14] Picard concludes that "[t]his could lead to a spiritual interpretation in some individuals." [174]

Parietal lobe

Andrew B. Newberg and Eugene G. d'Aquili, in their book Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief, take a perennial stance, describing their insights into the relationship between religious experience and brain function. [175] d'Aquili describes his own meditative experiences as "allowing a deeper, simpler part of him to emerge", which he believes to be "the truest part of who he is, the part that never changes." [175] Not content with personal and subjective descriptions like these, Newberg and d'Aquili have studied the brain-correlates to such experiences. They scanned the brain blood flow patterns during such moments of mystical transcendence, using SPECT-scans, to detect which brain areas show heightened activity. [176] Their scans showed unusual activity in the top rear section of the brain, the "posterior superior parietal lobe", or the "orientation association area (OAA)" in their own words. [177] This area creates a consistent cognition of the physical limits of the self. [178] This OAA shows a sharply reduced activity during meditative states, reflecting a block in the incoming flow of sensory information, resulting in a perceived lack of physical boundaries. [179] According to Newberg and d'Aquili,

This is exactly how Robert[ who? ] and generations of Eastern mystics before him have described their peak meditative, spiritual and mystical moments. [179]

Newberg and d'Aquili conclude that mystical experience correlates to observable neurological events, which are not outside the range of normal brain function. [180] They also believe that

...our research has left us no choice but to conclude that the mystics may be on to something, that the mind's machinery of transcendence may in fact be a window through which we can glimpse the ultimate realness of something that is truly divine. [181] [note 30]

Why God Won't Go Away "received very little attention from professional scholars of religion". [183] [note 31] [note 32] According to Bulkeley, "Newberg and D'Aquili seem blissfully unaware of the past half century of critical scholarship questioning universalistic claims about human nature and experience". [note 33] Matthew Day also writes that the discovery of a neurological substrate of a "religious experience" is an isolated finding which "doesn't even come close to a robust theory of religion". [185]

Default mode network

Recent studies evidenced the relevance of the default mode network in spiritual and self-transcending experiences. Its functions are related, among others, to self-reference and self-awareness, and new imaging experiments during meditation and the use of hallucinogens indicate a decrease in the activity of this network mediated by them, leading some studies to base on it a probable neurocognitive mechanism of the dissolution of the self, which occurs in some mystical phenomena. [11] [186] [187]

Psychiatry

A 2011 paper suggested that psychiatric conditions associated with psychotic spectrum symptoms may be possible explanations for revelatory-driven experiences and activities such as those of Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Saint Paul. It also proposed that the behavior of the followers of these religious figures could be explained through the lens of psychopathology and group dynamics. [188]

Psychedelic drugs

A number of studies by Roland R. Griffiths and other researchers have concluded that high doses of psilocybin and other classic psychedelics trigger mystical experiences in most research participants. [129] [189] [190] [191] Mystical experiences have been measured by a number of psychometric scales, including the Hood Mysticism Scale, the Spiritual Transcendence Scale, and the Mystical Experience Questionnaire. [191] The revised version of the Mystical Experience Questionnaire, for example, asks participants about four dimensions of their experience, namely the "mystical" quality, positive mood such as the experience of amazement, the loss of the usual sense of time and space, and the sense that the experience cannot be adequately conveyed through words. [191] The questions on the "mystical" quality in turn probe multiple aspects: the sense of "pure" being, the sense of unity with one's surroundings, the sense that what one experienced was real, and the sense of sacredness. [191] Some researchers have questioned the interpretation of the results from these studies and whether the framework and terminology of mysticism are appropriate in a scientific context, while other researchers have responded to those criticisms and argued that descriptions of mystical experiences are compatible with a scientific worldview. [192] [193] [194]