A kōan is a story, dialogue, question, or statement from Chinese Chan Buddhist lore, supplemented with commentaries, that is used in Zen Buddhist practice in different ways. The main goal of kōan practice in Zen is to achieve kenshō, to see or observe one's buddha-nature.

Jinul Puril Bojo Daesa, often called Jinul or Chinul for short, was a Korean monk of the Goryeo period, who is considered to be the most influential figure in the formation of Korean Seon (Zen) Buddhism. He is credited as the founder of the Jogye Order, by working to unify the disparate sects in Korean Buddhism into a cohesive organization.

Caodong school is a Chinese Chan Buddhist branch and one of the Five Houses of Chán.

Yunmen Wenyan, was a major Chinese Chan master of the Tang dynasty. He was a dharma-heir of Xuefeng Yicun.

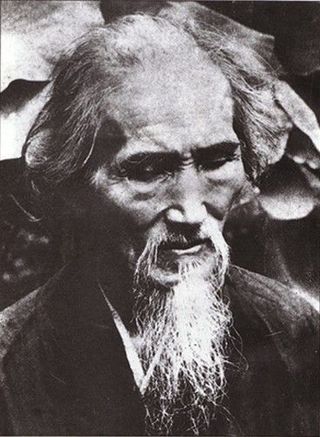

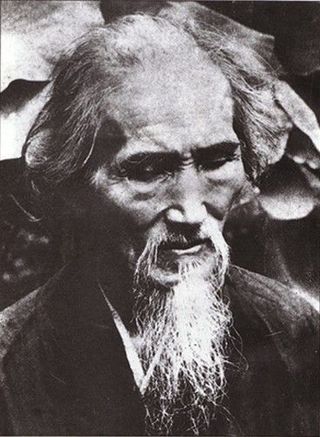

Xuyun or Hsu Yun was a renowned Chinese Chan Buddhist master and an influential Buddhist teacher of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135) was a Han Chinese Chan monk who compiled the Blue Cliff Record.

Dahui Zonggao was a 12th-century Chinese Chan (Zen) master. Dahui was a student of Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135) and was the 12th generation of the Linji school of Chan Buddhism. He was the dominant figure of the Linji school during the Song dynasty.

The Línjì school is a school of Chan Buddhism named after Linji Yixuan. It took prominence in Song China (960–1279), spread to Japan as the Rinzai school and influenced the nine mountain schools of Korean Seon.

Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty as the Chan School or the Buddha-mind school, and later developed into various sub-schools and branches. Zen was influenced by Taoism, especially Neo-Daoist thought, and developed as a distinguished school of Chinese Buddhism. From China, Chán spread south to Vietnam and became Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to Korea to become Seon Buddhism, and east to Japan, becoming Japanese Zen.

Hānshān Déqīng, was a leading Buddhist monk and poet of the late Ming dynasty China. He was also posthumously named Hongjue chanshi (弘覺大師). Hanshan was known for studying and teaching Pure Land, Huayan and Chán Buddhism. He is known as one of the four great masters of the Wanli Era Ming Dynasty, along with Yunqi Zhuhong (1535–1613) and Zibo Zhenke (1543–1603) both of whom he knew personally. He also wrote their biographies after their deaths.

Chan, from Sanskrit dhyāna, is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song dynasties.

The Five Houses of Chán were the five major schools of Chan Buddhism that originated during Tang China. Although at the time they were not considered formal schools or sects of Buddhism, they are now regarded as important schools in the history of Chán Buddhism. Most Chán lineages throughout Asia and the rest of the world originally grew from or were heavily influenced by the original five houses of Chán.

Zhenxie Qingliao, also known as Changlu Qingliao, was a Chinese Zen Buddhist monk during the Song Dynasty.

Though Zen is said to be based on a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not stand upon words", the Zen-tradition has a rich doctrinal and textual background. It has been influenced by sutras such as the Lankavatara Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Avatamsaka Sutra, and the Lotus Sutra.

Seon or Sŏn Buddhism is the Korean name for Chan Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism commonly known in English as Zen Buddhism. Seon is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Chan an abbreviation of 禪那 (chánnà), which is a Chinese transliteration of the Sanskrit word of dhyāna ("meditation"). Seon Buddhism, represented chiefly by the Jogye and Taego orders, is the most common type of Buddhism found in Korea.

Zen lineage charts depict the transmission of the dharma from one generation to another. They developed during the Tang dynasty, incorporating elements from Indian Buddhism and East Asian Mahayana Buddhism, but were first published at the end of the Tang.

Zen has a rich doctrinal background, despite the traditional Zen narrative which states that it is a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not stand upon words."

The Zen tradition is maintained and transferred by a high degree of institutionalisation, despite the emphasis on individual experience and the iconoclastic picture of Zen.

Modern scientific research on the history of Zen discerns three main narratives concerning Zen, its history and its teachings: Traditional Zen Narrative (TZN), Buddhist Modernism (BM), Historical and Cultural Criticism (HCC). An external narrative is Nondualism, which claims Zen to be a token of a universal nondualist essence of religions.

"Who is the master that sees and hears?" is a kōan-like form of self-inquiry practiced in the Zen tradition. It is best known from the 14th-century Japanese Zen Master Bassui Tokushō who pursued this question for many years. Similar examples of self-inquiry in Zen include, "Who is it that thus comes?" and "Who is the master that makes the grass green?"