A kōan is a story, dialogue, question, or statement from the Chinese Chan-lore, supplemented with commentaries, that is used in Zen practice to provoke the "great doubt" and initial insight of Zen-students. Prolonged koan-study shatters small-minded pride of, and identification with, this initial insight, and spurs further development of insight and compassion, and integration thereof in daily life and character.

Linji Yixuan was the founder of the Linji school of Chán Buddhism during Tang dynasty China.

Sōtō Zen or the Sōtō school is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism. It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Cáodòng school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Dòngshān Liánjiè. It emphasizes Shikantaza, meditation with no objects, anchors, or content. The meditator strives to be aware of the stream of thoughts, allowing them to arise and pass away without interference.

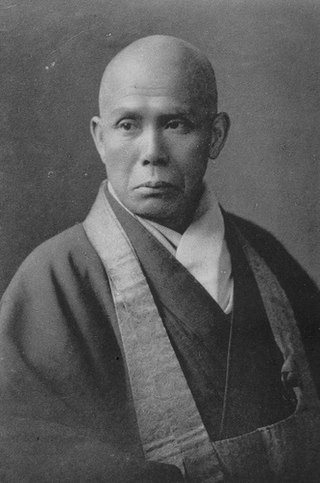

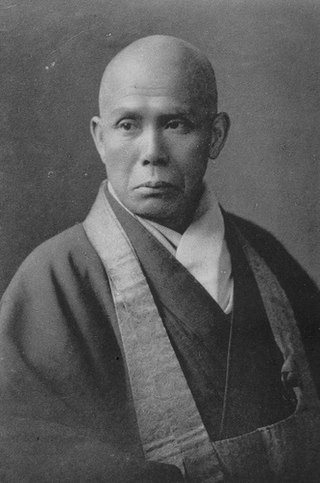

Soyen Shaku was the first Zen Buddhist master to teach in the United States. He was a rōshi of the Rinzai school and was abbot of both Kenchō-ji and Engaku-ji temples in Kamakura, Japan. Soyen was a disciple of Imakita Kosen.

The Rinzai school ,named after Linji Yixuan is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of Chan Buddhism was first transmitted to Japan by Myōan Eisai. Contemporary Japanese Rinzai is derived entirely from the Ōtōkan lineage transmitted through Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769), who is a major figure in the revival of the Rinzai tradition.

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese Mahāyāna school of Buddhism that strongly emphasizes dhyāna, the meditative training of awareness and equanimity. This practice, according to Zen proponents, gives insight into one's true nature, or the emptiness of inherent existence, which opens the way to a liberated way of living.

The First Zen Institute of America is a Rinzai institution for laypeople established by Sokei-an in New York, New York in 1930 as the Buddhist Society of America. The emphasis on lay practice has its roots in the history of the organization. In 1875, the Japanese Rinzai Zen master Imakita Kosen founded a Zen institute, Ryomokyo-kai, dedicated to reviving Zen in Japan by recruiting talented and educated lay people. Kosen's most celebrated disciple, Soyen Shaku, visited America in 1893 to attend the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago. In 1902 he returned to America where he lectured and taught briefly. Soyen Shaku assigned responsibility for this lay Zen institute to his heir, Sokatsu Shaku. The First Zen Institute's founder, Sokei-an, was Sokatsu's student and came to America with him in 1906 to establish a Zen community. When Sokatsu returned to Japan in 1910, Sokei-an remained to season his Zen and familiarize himself with the American character. After wandering across America and perfecting his English, Sokei-an made several trips back to Japan and in 1924 received credentials from Sokatsu as a Zen master.

Mary Farkas was the director of the First Zen Institute of America (FZIA), running the center's administrative functions for many years following the death of her teacher (Sokei-an) in 1945. Though she was not a teacher of Zen Buddhism in any traditional sense of the word, she did help to carry on the lineage of Sokei-an and also was editor of the FZIA's journal, Zen Notes, starting with Volume 1 in 1954. Additionally, she also edited books about Sokei-an, i.e. "The Zen Eye" and "Zen Pivots." Through her transcriptions of his talks, the institute was able to continue on the lineage without having a formal teacher.

Ryōmō Kyōkai (両忘協会 "Ryōmō Society", was a lay Rinzai Zen Buddhist Dharma center located in Tokyo, Japan.

Imakita Kōsen was a Japanese Rinzai Zen rōshi and Neo-Confucianist.

Gotō Zuigan was a Buddhist Rinzai Zen master the chief abbot of Myōshin-ji and Daitoku-ji temples, and a past president of Hanazono University of Kyoto, also known as "Rinzai University."

Below is a timeline of important events regarding Zen Buddhism in the United States. Dates with "?" are approximate.

Mumon Yamada was a Rinzai roshi, calligrapher, and former abbot of Shōfuku-ji in Kobe, Japan. Mumon was also the former head of the Myōshin-ji branch of the Rinzai school of Japan.

Ruth Fuller Sasaki, born Ruth Fuller, was an American writer and Buddhist teacher. She was important figure in the development of Buddhism in the United States. As Ruth Fuller Everett, she met and studied with Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki in Japan in 1930. In 1938, she became a principal supporter of the Buddhist Society of America, in New York. She married Sokei-an, the Zen priest in residence there, in 1944, but he died within a year. In 1949, she went to Kyoto to find another roshi to live and teach in New York, to complete translations of key Zen texts, and to pursue her own Zen training, receiving sanzen from Gotō Zuigan.

The Five Ranks is a poem consisting of five stanzas describing the stages of realization in the practice of Zen Buddhism. It expresses the interplay of absolute and relative truth and the fundamental non-dualism of Buddhist teaching.

Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty as the Chan School or the Buddha-mind school ", and later developed into various sub-schools and branches. From China, Chán spread south to Vietnam and became Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to Korea to become Seon Buddhism, and east to Japan, becoming Japanese Zen.

Tetsuo Sōkatsu (1870–1954) was a Japanese Rinzai-master. He was a dharma heir of Soyen Shaku.

Zen was introduced in the United States at the end of the 19th century by Japanese teachers who went to America to serve groups of Japanese immigrants and become acquainted with the American culture. After World War II, interest from non-Asian Americans grew rapidly. This resulted in the commencement of an indigenous American Zen tradition which also influences the larger western (Zen) world.

Modern scientific research on the history of Zen discerns three main narratives concerning Zen, its history and its teachings: Traditional Zen Narrative (TZN), Buddhist Modernism (BM), Historical and Cultural Criticism (HCC). An external narrative is Nondualism, which claims Zen to be a token of a universal nondualist essence of religions.

Zenrin-kushū is a collection of writings used in the Rinzai school of Zen. Initially it was a compilation of Zen writings by Tōyō Eichō a disciple of Kanzan Egen of the Myōshin-ji line of Rinzai school in Kyoto, Japan. Tōyō's anthology consisted of 5,000 writings compiled from writings of various traditions, such as Confucianism, Taoism and Zen, and the poetry of Tang and Song China.