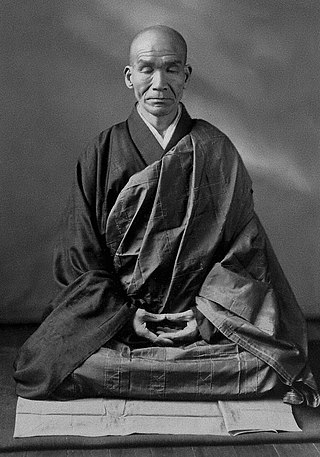

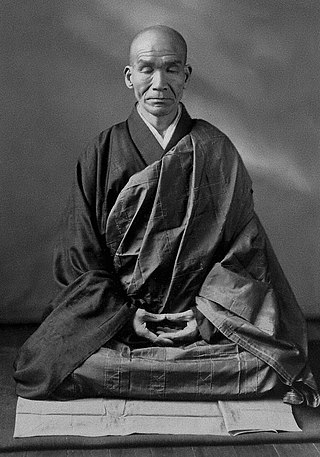

Dōgen Zenji, was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (道元希玄), Eihei Dōgen (永平道元), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (高祖承陽大師), and Busshō Dentō Kokushi (仏性伝東国師).

Zazen is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

Sōtō Zen or the Sōtō school is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism. It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Cáodòng school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Dòngshān Liánjiè. It emphasizes Shikantaza, meditation with no objects, anchors, or content. The meditator strives to be aware of the stream of thoughts, allowing them to arise and pass away without interference.

Ōbaku Zen or the Ōbaku school is one of three main schools of Japanese Zen Buddhism, in addition to the Sōtō and Rinzai schools. The school was founded in Japan by the Chinese monk Ingen Ryūki, who immigrated to Japan during the Manchu conquest of China in the 17th century.

Eihei-ji (永平寺) is one of two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism, the largest single religious denomination in Japan. Eihei-ji is located about 15 km (9 mi) east of Fukui in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. In English, its name means "temple of eternal peace".

The Rinzai school, named after Linji Yixuan is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of Chan Buddhism was first transmitted to Japan by Myōan Eisai. Contemporary Japanese Rinzai is derived entirely from the Ōtōkan lineage transmitted through Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769), who is a major figure in the revival of the Rinzai tradition.

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese Mahāyāna school of Buddhism that strongly emphasizes dhyāna, the meditative training of awareness and equanimity. This practice, according to Zen proponents, gives insight into one's true nature, or the emptiness of inherent existence, which opens the way to a liberated way of living.

Shōhaku Okumura is a Japanese Sōtō Zen priest and the founder and abbot of the Sanshin Zen Community located in Bloomington, Indiana, where he and his family currently live. From 1997 until 2010, Okumura also served as director of the Sōtō Zen Buddhism International Center in San Francisco, California, which is an administrative office of the Sōtō school of Japan.

Sanshin Zen Community is a Soto Zen sangha based at the temple Sanshin-ji in Bloomington, Indiana founded by Shohaku Okumura.

Gentō Sokuchū was a Sōtō Zen priest and the 50th abbot of Eihei-ji, the school's head temple. He was part of a 17th and 18th century movement within the Sōtō school that sought to bring the school's teachings back in line with those of the 13th century founding teacher, Dōgen. To this end, he edited major editions of works by Dōgen and succeeded in disseminating them widely. He is best remembered for compiling the Eihei Rules of Purity, a collection of writings by Dōgen laying out a strict code of conduct for monks. These rules had been largely unheeded in the school in the preceding several centuries, and Gentō used his high position as abbot of Eihei-ji to reintroduce and enforce them. His work on the Eihei Rules of Purity was completed in 1794 while he was serving as the eleventh abbot of Entsū-ji. The following year he became the 50th abbot of Eihei-ji. He was also involved in editing Dōgen's master work, the Shōbōgenzō.

Taigen Dan Leighton is a Sōtō priest and teacher, academic, and author. He is an authorized lineage holder and Zen teacher in the tradition of Shunryū Suzuki and is the founder and Guiding Teacher of Ancient Dragon Zen Gate in Chicago, Illinois. Leighton is also an authorized teacher in the Japanese Sōtō School (kyōshi).

Jisho Warner is a Sōtō Zen priest and abiding teacher of Stone Creek Zen Center in Sonoma County, California. Warner is a former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association, and its first female and first LGBTQ president. Having graduated from Harvard University in 1965, she became an artist and freelance editor. She has edited books by Robert Thurman, Ed Brown, Wendy Johnson, Jane Hirshfield, Dainin Katagiri, and many others. She is a co-editor of the book Opening the Hand of Thought by Kosho Uchiyama, whose teachings she first encountered in the 1980s while practicing at the Pioneer Valley Zendo in Massachusetts under Koshi Ichida.

Bendōwa (辨道話), meaning Discourse on the Practice of the Way or Dialogue on the Way of Commitment, sometimes also translated as Negotiating the Way, On the Endeavor of the Way, or A Talk about Pursuing the Truth, is an influential essay written by Dōgen, the founder of Zen Buddhism's Sōtō school in Japan.

Tenzo Kyōkun (典座教訓), usually rendered in English as Instructions for the Cook, is an important essay written by Dōgen, the founder of Zen Buddhism's Sōtō school in Japan.

The Zen tradition is maintained and transferred by a high degree of institutionalisation, despite the emphasis on individual experience and the iconoclastic picture of Zen.

Maka hannya haramitsu, the Japanese transliteration of Mahāprajñāpāramitā meaning The Perfection of Great Wisdom, is the second book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It is the second book in not only the original 60 and 75 fascicle versions of the text, but also the later 95 fascicle compilations. It was written in Kyoto in the summer of 1233, the first year that Dōgen began occupying the temple that what would soon become Kōshōhōrin-ji. As the title suggests, this chapter lays out Dōgen's interpretation of the Mahaprajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sūtra, or Heart Sutra, so called because it is supposed to represent the heart of the 600 volumes of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra. The Heart Sutra focuses on the Buddhist concept of prajñā, or wisdom, which indicates not conventional wisdom, but rather wisdom regarding the emptiness of all phenomena. As Dōgen argues in this chapter, prajñā is identical to the practice of zazen, not a way of thinking.

Daigo, also known in English translation as Great Realization, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. The book appears tenth in the 75 fascicle version of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 26th in the later chronological 95 fascicle "Honzan edition". It was presented to his students in the first month of 1242 at Kōshōhōrin-ji, the first monastery established by Dōgen, located in Kyoto. According to Gudō Nishijima, a modern Zen priest, the "great realization" to which Dōgen refers is not an intellectual idea, but rather a "concrete realization of facts in reality" or "realization in real life". Shōhaku Okumura, another modern-day Zen teacher, writes that Dōgen equates the term daigo with the network of interdependence in which all beings in the universe exist rather than something that we lack and need to obtain. Given this, Okumura writes that Dōgen is encouraging us to, "to realize great realization within this great realization, moment by moment; or perhaps it is better to say that great realization realizes great realization through our practice."

Shōryū Bradley is a Sōtō Zen priest and the founder and abbot of Gyobutsuji Zen Monastery located near Kingston, Arkansas.

Daichi Sokei (大智祖継) (1290–1366) was a Japanese Sōtō Zen monk famous for his Buddhist poetry who lived during the late Kamakura period and early Muromachi period. According to Steven Heine, a Buddhist studies professor, "Daichi is unique in being considered one of the great medieval Zen poets during an era when Rinzai monks, who were mainly located in Kyoto or Kamakura, clearly dominated the composition of verse."