Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system, its functions, and its disorders. It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, developmental biology, cytology, psychology, physics, computer science, chemistry, medicine, statistics, and mathematical modeling to understand the fundamental and emergent properties of neurons, glia and neural circuits. The understanding of the biological basis of learning, memory, behavior, perception, and consciousness has been described by Eric Kandel as the "epic challenge" of the biological sciences.

Broca's area, or the Broca area, is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Cognitive neuroscience is the scientific field that is concerned with the study of the biological processes and aspects that underlie cognition, with a specific focus on the neural connections in the brain which are involved in mental processes. It addresses the questions of how cognitive activities are affected or controlled by neural circuits in the brain. Cognitive neuroscience is a branch of both neuroscience and psychology, overlapping with disciplines such as behavioral neuroscience, cognitive psychology, physiological psychology and affective neuroscience. Cognitive neuroscience relies upon theories in cognitive science coupled with evidence from neurobiology, and computational modeling.

The development of the nervous system, or neural development (neurodevelopment), refers to the processes that generate, shape, and reshape the nervous system of animals, from the earliest stages of embryonic development to adulthood. The field of neural development draws on both neuroscience and developmental biology to describe and provide insight into the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which complex nervous systems develop, from nematodes and fruit flies to mammals.

Functional neuroimaging is the use of neuroimaging technology to measure an aspect of brain function, often with a view to understanding the relationship between activity in certain brain areas and specific mental functions. It is primarily used as a research tool in cognitive neuroscience, cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and social neuroscience.

Behavioral neuroscience, also known as biological psychology, biopsychology, or psychobiology, is part of the broad, interdisciplinary field of neuroscience, with its primary focus being on the biological and neural substrates underlying human experiences and behaviors, as in our psychology. Derived from an earlier field known as physiological psychology, behavioral neuroscience applies the principles of biology to study the physiological, genetic, and developmental mechanisms of behavior in humans and other animals. Behavioral neuroscientists examine the biological bases of behavior through research that involves neuroanatomical substrates, environmental and genetic factors, effects of lesions and electrical stimulation, developmental processes, recording electrical activity, neurotransmitters, hormonal influences, chemical components, and the effects of drugs. Important topics of consideration for neuroscientific research in behavior include learning and memory, sensory processes, motivation and emotion, as well as genetic and molecular substrates concerning the biological bases of behavior. Subdivisions of behavioral neuroscience include the field of cognitive neuroscience, which emphasizes the biological processes underlying human cognition. Behavioral and cognitive neuroscience are both concerned with the neuronal and biological bases of psychology, with a particular emphasis on either cognition or behavior depending on the field.

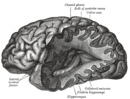

The longitudinal fissure is the deep groove that separates the two cerebral hemispheres of the vertebrate brain. Lying within it is a continuation of the dura mater called the falx cerebri. The inner surfaces of the two hemispheres are convoluted by gyri and sulci just as is the outer surface of the brain.

The planum temporale is the cortical area just posterior to the auditory cortex within the Sylvian fissure. It is a triangular region which forms the heart of Wernicke's area, one of the most important functional areas for language. Original studies on this area found that the planum temporale was one of the most asymmetric regions in the brain, larger in the left cerebral hemisphere than the right.

Von Economo neurons, also called spindle neurons, are a specific class of mammalian cortical neurons characterized by a large spindle-shaped soma gradually tapering into a single apical axon in one direction, with only a single dendrite facing opposite. Other cortical neurons tend to have many dendrites, and the bipolar-shaped morphology of von Economo neurons is unique here.

A mirror neuron is a neuron that fires both when an animal acts and when the animal observes the same action performed by another. Thus, the neuron "mirrors" the behavior of the other, as though the observer were itself acting. Mirror neurons are not always physiologically distinct from other types of neurons in the brain; their main differentiating factor is their response patterns. By this definition, such neurons have been directly observed in humans and other primates, and in birds.

Social neuroscience is an interdisciplinary field devoted to understanding the relationship between social experiences and biological systems. Humans are fundamentally a social species, and studies indicate that various social influences, including life events, poverty, unemployment and loneliness can influence health related biomarkers. Still a young field, social neuroscience is closely related to personality neuroscience, affective neuroscience and cognitive neuroscience, focusing on how the brain mediates social interactions. The biological underpinnings of social cognition are investigated in social cognitive neuroscience.

Developmental cognitive neuroscience is an interdisciplinary scientific field devoted to understanding psychological processes and their neurological bases in the developing organism. It examines how the mind changes as children grow up, interrelations between that and how the brain is changing, and environmental and biological influences on the developing mind and brain.

Integrative neuroscience is the study of neuroscience that works to unify functional organization data to better understand complex structures and behaviors. The relationship between structure and function, and how the regions and functions connect to each other. Different parts of the brain carrying out different tasks, interconnecting to come together allowing complex behavior. Integrative neuroscience works to fill gaps in knowledge that can largely be accomplished with data sharing, to create understanding of systems, currently being applied to simulation neuroscience: Computer Modeling of the brain that integrates functional groups together.

Disgust is an emotional response of rejection or revulsion to something potentially contagious or something considered offensive, distasteful or unpleasant. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin wrote that disgust is a sensation that refers to something revolting. Disgust is experienced primarily in relation to the sense of taste, and secondarily to anything which causes a similar feeling by sense of smell, touch, or vision. Musically sensitive people may even be disgusted by the cacophony of inharmonious sounds. Research has continually proven a relationship between disgust and anxiety disorders such as arachnophobia, blood-injection-injury type phobias, and contamination fear related obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Cultural neuroscience is a field of research that focuses on the interrelation between a human's cultural environment and neurobiological systems. The field particularly incorporates ideas and perspectives from related domains like anthropology, psychology, and cognitive neuroscience to study sociocultural influences on human behaviors. Such impacts on behavior are often measured using various neuroimaging methods, through which cross-cultural variability in neural activity can be examined.

A number of studies have found that human biology can be linked with political orientation. This means that an individual's biology may predispose them to a particular political orientation and ideology or, conversely, that subscription to certain ideologies may predispose them to measurable biological and health outcomes.

The biological basis of personality is a collection of brain systems and mechanisms that underlie human personality. Human neurobiology, especially as it relates to complex traits and behaviors, is not well understood, but research into the neuroanatomical and functional underpinnings of personality are an active field of research. Animal models of behavior, molecular biology, and brain imaging techniques have provided some insight into human personality, especially trait theories.

Neuromorality is an emerging field of neuroscience that studies the connection between morality and neuronal function. Scientists use fMRI and psychological assessment together to investigate the neural basis of moral cognition and behavior. Evidence shows that the central hub of morality is the prefrontal cortex guiding activity to other nodes of the neuromoral network. A spectrum of functional characteristics within this network to give rise to both altruistic and psychopathological behavior. Evidence from the investigation of neuromorality has applications in both clinical neuropsychiatry and forensic neuropsychiatry.

Neural synchrony is the correlation of brain activity across two or more people over time. In social and affective neuroscience, neural synchrony specifically refers to the degree of similarity between the spatio-temporal neural fluctuations of multiple people. This phenomenon represents the convergence and coupling of different people's neurocognitive systems, and it is thought to be the neural substrate for many forms of interpersonal dynamics and shared experiences. Some research also refers to neural synchrony as inter-brain synchrony, brain-to-brain coupling, inter-subject correlation, between-brain connectivity, or neural coupling. In the current literature, neural synchrony is notably distinct from intra-brain synchrony—sometimes also called neural synchrony—which denotes the coupling of activity across regions of a single individual's brain.

Alexander T. Sack is a German neuroscientist and cognitive psychologist. He is currently appointed as a full professor and chair of applied cognitive neuroscience at the Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience at Maastricht University. He is also co-founder and board member of the Dutch-Flemish Brain Stimulation Foundation, director of the International Clinical TMS Certification Course, co-director of the Center for Integrative Neuroscience (CIN) and the Scientific Director of the Transcranial Brain Stimulation Policlinic at Maastricht University Medical Centre.