"Art and Revolution" (original German title "Die Kunst und die Revolution") is a long essay by the composer Richard Wagner, originally published in 1849. It sets out some of his basic ideas about the role of art in society and the nature of opera.

"Art and Revolution" (original German title "Die Kunst und die Revolution") is a long essay by the composer Richard Wagner, originally published in 1849. It sets out some of his basic ideas about the role of art in society and the nature of opera.

Wagner had been an enthusiast for the revolutions of 1848 and had been an active participant in the Dresden Revolution of 1849, as a consequence of which he was forced to live for many years in exile from Germany. "Art and Revolution" was one of a group of polemical articles he published in his exile. His enthusiasm for such writing at this stage of his career is in part explained by his inability, in exile, to have his operas produced. But it was also an opportunity for him to express and justify his deep-seated concerns about the true nature of opera as music drama at a time when he was beginning to write his libretti for his Ring cycle, and turning his thoughts to the type of music it would require. This was quite different from the music of popular grand operas of the period, which Wagner believed were a sell-out to commercialism in the arts. "Art and Revolution" therefore explained his ideals in the context of the failure of the 1848 revolutions to bring about a society like that which Wagner conceived to have existed in Ancient Greece—truly dedicated to, and which could be morally sustained by, the arts—which for Wagner meant, supremely, his conception of drama.

Wagner wrote the essay over two weeks in Paris [1] and sent it to a French political journal, the National; they refused it, but it was published in Leipzig and ran to a second edition.

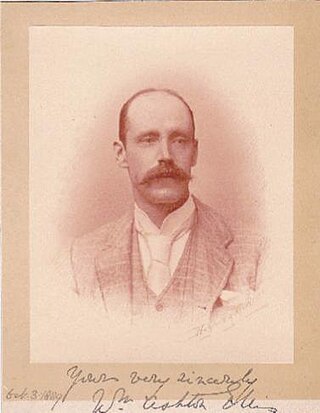

The following summary is based on the standard translation of Wagner's prose works by William Ashton Ellis, first published in 1895. Quotations are taken from this translation.

Wagner notes that artists complain that economic uncertainty following the 1848 revolutions has damaged their prospects. But such materialistic complaints are selfish and unjustified. Those who practised art for art's sake "suffered also in the former times when others were rejoicing". [2] He therefore undertakes an examination of the role of art in society, commencing with a historical review starting in Ancient Greece.

He extols the Apollonian spirit, embodied in the tragedies of Aeschylus, as "the highest conceivable form of Art – the DRAMA". [3] But the fall of the Athenian state meant that philosophy, rather than art, dominated European society. Wagner portrays the Romans as brutal and sensuous, and the Church as having hypocritically betrayed Jesus's gospel of Universal Love. "The Greek ... could procreate Art for the very joy of manhood; the Christian, who impartially cast aside both Nature and himself; could only sacrifice to his God on the altar of renunciation; he durst not bring his actions or his work as offering, but believed that he must seek His favour by abstinence from all self-prompted venture." [4] The worldly power of Christendom indeed "had its share in the revival of art" by patronage of artists celebrating its own supremacy. Moreover, "the security of riches awoke in the ruling classes the desire for more refined enjoyment of their wealth". [5] Modern changes in society have resulted in the catastrophe that art has sold "her soul and body to a far worse mistress - Commerce." [6]

The modern stage offers two irreconcilable genres, split from Wagner's Greek ideal - the play, which lacks "the idealising influence of music", and opera which is "forestalled of the living heart and lofty purpose of actual drama". [7] Moreover, opera is enjoyed specifically because of its superficial sensationalism. In a critique which lies at the heart of much of his writings at this period and thereafter, (and which is a clear dig at composers such as Giacomo Meyerbeer), Wagner complains:

There are even many of our most popular artists who do not in the least conceal the fact, that they have no other ambition than to satisfy this shallow audience. They are wise in their generation; for when the prince leaves a heavy dinner, the banker a fatiguing financial operation, the working man a weary day of toil, and go to the theatre: they ask for rest, distraction, and amusement, and are in no mood for renewed effort and fresh expenditure of force. This argument is so convincing, that we can only reply by saying: it would be more decorous to employ for this purpose any other thing in the wide world, but not the body and soul of Art. We shall then be told, however, that if we do not employ Art in this manner, it must perish from out our public life: i.e.,—that the artist will lose the means of living. [8]

Wagner continues by comparing many features of contemporary art and art practice to those of Ancient Greece, always of course to the detriment of the former; some of this decay was due to the introduction in the ancient world of slave-labour, to which Wagner links contemporary wage labour; concluding this section by asserting that the Greeks had formed the perfect Art-work (i.e. Wagner's own conception of Greek drama), whose nature we have lost.

Only the great Revolution of Mankind, whose beginnings erstwhile shattered Grecian Tragedy, can win for us this Art-work. For only this Revolution can bring forth from its hidden depths, in the new beauty of a nobler Universalism, that which it once tore from the conservative spirit of a time of beautiful but narrow-meted culture—and tearing it, engulphed. [9]

This revolution consists for Wagner of a not very clearly defined return to Nature. Elements of this are a condemnation of the rich and "the mechanic's pride in the moral consciousness of his labour", not however to be confused with "the windy theories of our socialistic doctrinaires" who believe that society might be reconstructed without overthrow. Wagner's goal is "the strong fair Man, to whom Revolution shall give his Strength, and Art his Beauty!" [10]

Wagner then berates those who simply dismiss these ideas as utopian. Reconciling his two main inspirations, Wagner concludes "Let us therefore erect the altar of the future, in Life as in the living Art, to the two sublimest teachers of mankind:—Jesus, who suffered for all men; and Apollo, who raised them to their joyous dignity!" [11]

Wagner's idealism of ancient Greece was common among his romantic intellectual circle (for example, his Dresden friend the architect Gottfried Semper wrote to demonstrate the ideal qualities of classical Greek architecture). Although Wagner at the time imagined his intended operas to constitute the "perfect Art-works" mentioned in this essay and described further in "The Artwork of the Future" and "Opera and Drama", with the aim of redeeming society through art, in the event practicality superseded the naive ideas (and shallow historical interpretation) expressed in these essays. However, the concept of music drama as Wagner eventually forged it is undoubtedly rooted in the ideas he expressed at this time. Indeed, the essay is notable among other things for Wagner's first use of the term Gesamtkunstwerk (total art work)—in this case referring to his view of Greek drama as combining music, dance and poetry, rather than his later application of the term to his own works.

Curt von Westernhagen also detects in the essay the influence of Proudhon's What is Property? which Wagner read in June 1849. [12]

In 1872, by which time he was no longer an outcast, but had established himself as a leading artist, Wagner wrote a new introduction to the essay. He began by quoting Thomas Carlyle's History of Frederick the Great (1858–1865), feeling himself "in complete accord" with Carlyle's call in the aftermath of the "Spontaneous Combustion" of revolution and resulting "Millennium of Anarchies" to "abridge it, spend your heart's-blood upon abridging it, ye Heroic Wise that are to come!" As Wagner explains, "I believed in the Revolution, and in its unrestrainable necessity ... only, I also felt that I was called to point out to it the way of rescue. ... It is needless to recall the scorn which my presumption brought upon me ...". [13] The essay, the first of a series of polemical blasts from Wagner in the years 1849 to 1852, which included "The Artwork of the Future" and "Jewishness in Music", indeed provided fuel to those who wished to characterize Wagner as an impractical and/or eccentric radical idealist.

Wagner had however been writing in part to deliberately provoke, on the basis that any notoriety was better than no notoriety. In a letter of June 1849 to Franz Liszt, one of his few influential allies at the time, he wrote "I must make people afraid of me. Well, I have no money, but what I do have is an enormous desire to commit acts of artistic terrorism"; [14] without denying the sincerity of Wagner's views at the time of writing, this article can be seen perhaps as one of those acts.

During and immediately after the Russian Revolution of 1917, the ideas of Wagner's "Art and Revolution" were influential in the proletarian art movement and on the ideas of those such as Platon Kerzhentsev, the theorist of Proletcult Theatre. [15]

The song "The Damnation Slumbereth Not" by the band Half Man Half Biscuit on their 2002 album Cammell Laird Social Club includes a slightly-modified quotation from the essay: [16] [17]

Well of course music these days is the slave of mammon and as a result

It has become corrupt and shallow

Its real essence is industry

Its moral purpose is the acquisition of money

Its aesthetic pretext is the entertainment of those who are bored

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas. Unlike most opera composers, Wagner wrote both the libretto and the music for each of his stage works. Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works in the romantic vein of Carl Maria von Weber and Giacomo Meyerbeer, Wagner revolutionised opera through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, by which he sought to synthesise the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama. He described this vision in a series of essays published between 1849 and 1852. Wagner realised these ideas most fully in the first half of the four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Der Ring des Nibelungen, WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the Nibelungenlied. The composer termed the cycle a "Bühnenfestspiel", structured in three days preceded by a Vorabend. It is often referred to as the Ring cycle, Wagner's Ring, or simply The Ring.

Das Rheingold, WWV 86A, is the first of the four epic music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. It was performed, as a single opera, at the National Theatre Munich on 22 September 1869, and received its first performance as part of the Ring cycle at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, on 13 August 1876.

Die Walküre, WWV 86B, is the second of the four epic music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. It was performed, as a single opera, at the National Theatre Munich on 26 June 1870, and received its first performance as part of the Ring cycle at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus on 14 August 1876.

Gottfried Semper was a German architect, art critic, and professor of architecture who designed and built the Semper Opera House in Dresden between 1838 and 1841. In 1849 he took part in the May Uprising in Dresden and was put on the government's wanted list. He fled first to Zürich and later to London. He returned to Germany after the 1862 amnesty granted to the revolutionaries.

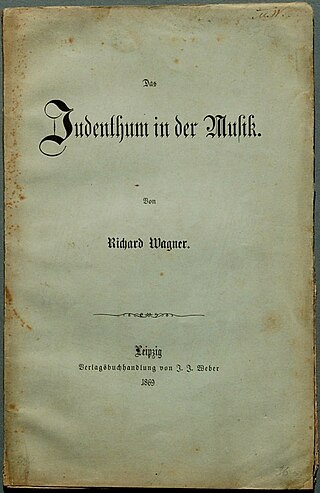

"Das Judenthum in der Musik", is an essay by composer Richard Wagner which criticizes the influence of Jews and their "essence" on European art music, arguing that they have not contributed to its development but have rather commodified and degraded it.

The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music is an 1872 work of dramatic theory by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. It was reissued in 1886 as The Birth of Tragedy, Or: Hellenism and Pessimism. The later edition contained a prefatory essay, "An Attempt at Self-Criticism", wherein Nietzsche commented on this earlier book.

A Gesamtkunstwerk is a work of art that makes use of all or many art forms or strives to do so. The term is a German loanword accepted in English as a term in aesthetics.

Nietzsche contra Wagner; Out of the Files of a Psychologist is a critical essay by Friedrich Nietzsche, composed of selections he chose from among his earlier works. The selections are assembled in this essay in order to focus on Nietzsche's thoughts about the composer Richard Wagner. As he says in the preface, when the selections are read "one after the other they will leave no doubt either about Richard Wagner or about myself: we are antipodes." He also describes it as "an essay for psychologists, but not for Germans". It was written in his last year of lucidity (1888–1889), and published by C. G. Naumann in Leipzig in 1889. Nietzsche describes in this short work why he parted ways with his one-time idol and friend, Richard Wagner. Nietzsche attacks Wagner's views, expressing disappointment and frustration in Wagner's life choices. Nietzsche evaluates Wagner's philosophy on tonality, music and art; he admires Wagner's power to emote and express himself, but largely disdains what the philosopher deems his religious biases.

The evolution of Richard Wagner's epic operatic tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen was a long and tortuous process, and the precise sequence of events which led the composer to embark upon such a vast undertaking is still unclear. The composition of the text took place between 1848 and 1853, when all four libretti were privately printed; but the closing scene of the final opera, Götterdämmerung, was revised a number of times between 1856 and 1872. The names of the last two Ring operas, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, were probably not definitively settled until 1856.

The German composer Richard Wagner was a controversial figure during his lifetime, and has continued to be so after his death. Even today he is associated in the minds of many with Nazism and his operas are often thought to extol the virtues of German nationalism. The writer and Wagner scholar Bryan Magee has written:

I sometimes think there are two Wagners in our culture, almost unrecognizably different from one another: the Wagner possessed by those who know his work, and the Wagner imagined by those who know him only by name and reputation.

Opera and Drama is a book-length essay written by Richard Wagner in 1851 setting out his ideas on the ideal characteristics of opera as an art form. It belongs with other essays of the period in which Wagner attempted to explain and reconcile his political and artistic ideas, at a time when he was working on the libretti, and later the music, of his Ring cycle.

"The Artwork of the Future" is a long essay written by Richard Wagner, first published in 1849 in Leipzig, in which he sets out some of his ideals on the topics of art in general and music drama in particular.

"Music of the Future" is the title of an essay by Richard Wagner, first published in French translation in 1860 as "La musique de l'avenir" and published in the original German in 1861. It was intended to introduce the librettos of Wagner's operas to a French audience at the time when he was hoping to launch in Paris a production of Tannhäuser, and sets out a number of his desiderata for true opera, including the need for 'endless melody'. Wagner deliberately put the title in quotation marks to distance himself from the term; Zukunftsmusik had already been adopted, both by Wagner's enemies, in the 1850s, often as a deliberate misunderstanding of the ideas set out in Wagner's 1849 essay, The Artwork of the Future, and by his supporters, notably Franz Liszt. Wagner's essay seeks to explain why the term is inadequate, or inappropriate, for his approach.

Wieland der Schmied is a draft by Richard Wagner for an opera libretto based on the Germanic legend of Wayland Smith. It is listed in the Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis as WWV82.

"Eine Mitteilung an meine Freunde", usually referred to in English by its translated title of "A Communication to My Friends", is an extensive autobiographical work by Richard Wagner, published in 1851, in which he sought to justify his innovative concepts on the future of opera in general, and his own proposed works in particular.

Carl August Röckel was a German composer and conductor. He was a friend of Richard Wagner and active in the German revolutions of 1848–1849.

Wieland der Schmied(Wieland the Smith; Slovak: Kováč Wieland) is an opera in three acts by Ján Levoslav Bella first performed in 1926, to a libretto by Oskar Schlemm based on an original libretto draft by Richard Wagner.

William Ashton Ellis was an English doctor and theosophist. He is remembered for translating the complete prose works of Richard Wagner.