Diarmait Mac Murchada, was King of Leinster in Ireland from 1127 to 1171. In 1167, he was deposed by the High King of Ireland, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair. To recover his kingdom, Mac Murchada solicited help from King Henry II of England. His issue unresolved, he gained the military support of the Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, thus initiating the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland.

Echmarcach mac Ragnaill was a dominant figure in the eleventh-century Irish Sea region. At his height, he reigned as king over Dublin, the Isles, and perhaps the Rhinns of Galloway. The precise identity of Echmarcach's father, Ragnall, is uncertain. One possibility is that this man was one of two eleventh-century rulers of Waterford. Another possibility is that Echmarcach's father was an early eleventh-century ruler of the Isles. If any of these identifications are correct, Echmarcach may have been a member of the Uí Ímair kindred.

Godred Crovan, known in Gaelic as Gofraid Crobán, Gofraid Meránach, and Gofraid Méránach, was a Norse-Gaelic ruler of the kingdoms of Dublin and the Isles. Although his precise parentage has not completely been proven, he was certainly an Uí Ímair dynast, and a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán, King of Northumbria and Dublin.

Dearbhfhorghaill (1108–1193), anglicised as Derval, was a daughter of Murchad Ua Maeleachlainn, king of Meath, and of his wife Mor, daughter of Muirchertach Ua Briain. She is famously known as the "Helen of Ireland" as her abduction from her husband Tigernán Ua Ruairc by Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster, in 1152 played some part in bringing the Anglo-Normans to Irish shores, although this is a role that has often been greatly exaggerated and often misinterpreted.

Tighearnán Mór Ua Ruairc, anglicised as Tiernan O'Rourke ruled the kingdom of Breifne as the 19th king in its Ua Ruairc dynasty, a branch of the Uí Briúin. As one of the provincial kings in Ireland in the twelfth century, he constantly expanded his kingdom through shifting alliances, of which the most long-standing was with Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair King of Connacht and High King of Ireland, and subsequently his son and successor Ruaidhrí Ua Conchobair. He is known for his role in the expulsion of Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster, from Ireland in 1166. Mac Murchada's subsequent recruitment of Marcher Lords to assist him in the recovery of his Kingdom of Leinster ultimately led to the Norman invasion of Ireland.

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land from the Irish, over which the kings of England then claimed sovereignty, all allegedly sanctioned by the papal bull Laudabiliter. At the time, Gaelic Ireland was made up of several kingdoms, with a High King claiming lordship over most of the other kings. The Anglo-Norman invasion was a watershed in Ireland's history, marking the beginning of more than 800 years of direct English and, later, British, conquest and colonialism in Ireland.

Guðrøðr Óláfsson was a twelfth-century ruler of the kingdoms of Dublin and the Isles. Guðrøðr was a son of Óláfr Guðrøðarson and Affraic, daughter of Fergus, Lord of Galloway. Throughout his career, Guðrøðr battled rival claimants to the throne, permanently losing about half of his realm to a rival dynasty in the process. Although dethroned for nearly a decade, Guðrøðr clawed his way back to regain control of a partitioned kingdom, and proceeded to project power into Ireland. Although originally opposed to the English invasion of Ireland, Guðrøðr adeptly recognised the English ascendancy in the Irish Sea region and aligned himself with the English. All later kings of the Crovan dynasty descended from Guðrøðr.

Óttar of Dublin, in Irish Oitir Mac mic Oitir, was a Hiberno-Norse King of Dublin, reigning in 1142–1148. Alternative names used in modern scholarship include Óttar of the Isles and Óttar Óttarsson.

Affreca de Courcy or Affrica Guðrøðardóttir was a late 12th-/early 13th century noblewoman. She was the daughter of Godred Olafsson, King of the Isles, a member of the Crovan dynasty. In the late 12th century she married John de Courcy. Affrica is noted for religious patronage in northern Ireland.

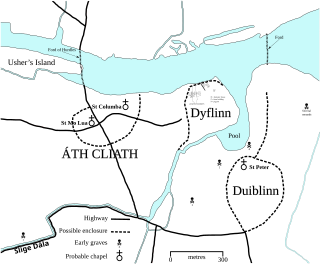

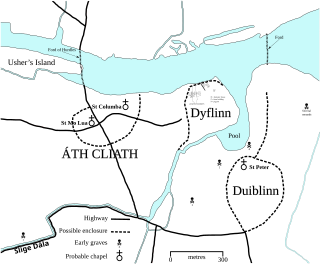

Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill was a late eleventh-century King of Dublin. Although the precise identities of his father and grandfather are uncertain, Gofraid was probably a kinsman of his royal predecessor, Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles. Gofraid lived in an era when control of the Kingdom of Dublin was fought over by competing Irish overlords. In 1052, for example, Echmarcach was forced from the kingdom by the Uí Chennselaig King of Leinster, Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó. When the latter died in 1072, Dublin was seized by the Uí Briain King of Munster, Toirdelbach Ua Briain, a man who either handed the Dublin kingship over to Gofraid, or at least consented to Gofraid's local rule.

Ímar mac Arailt was an eleventh-century ruler of the Kingdom of Dublin and perhaps the Kingdom of the Isles. He was the son of a man named Aralt, and appears to have been a grandson of Amlaíb Cuarán, King of Northumbria and Dublin. Such a relationship would have meant that Ímar was a member of the Uí Ímair, and that he was a nephew of Amlaíb Cuarán's son, Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, King of Dublin, a man driven from Dublin by Echmarcach mac Ragnaill in 1036.

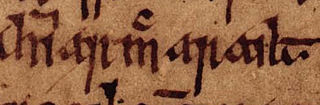

Brodar mac Torcaill, also known as Brodar Mac Turcaill, was a late twelfth century King of Dublin. He was a member of the Meic Torcaill, a substantial landholding kindred in the kingdom. His death in 1160, at the hands of the Meic Gilla Sechnaill of South Brega, is revealed by the thirteenth-century Cottonian Annals, the seventeenth-century Annals of the Four Masters, the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster, and the fourteenth-century Annals of Tigernach.

Ragnall mac Torcaill was a twelfth-century Norse-Gaelic magnate who may have been King of Dublin. He was a member of the Meic Torcaill, and may be identical to a member of this family who campaigned in Wales in 1144. Ragnall was slain in 1146, with some sources styling him king in records of his demise. He was the father of at least one son, Ascall, a man who certainly reigned as king.

Domnall Gerrlámhach, also known as Domnall Gerrlámhach Ua Briain, Domnall mac Muirchertaig, and Domnall Ua Briain, was an obscure twelfth-century Uí Briain dynast and King of Dublin. He was one of two sons of Muirchertach Ua Briain, High King of Ireland. Domnall's father appears to have installed him as King of Dublin in the late eleventh- or early twelfth century, which suggests that he was his father's successor-designate. Although Domnall won a remarkable victory in the defence of the Kingdom of Dublin in the face of an invasion from the Kingdom of Leinster in 1115, he failed to achieve the successes of his father. After his final expulsion from Dublin at the hands of Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht, and the death of his father, Domnall disappears from record until his own death in 1135. He was perhaps survived by two sons.

Domnall mac Taidc was the ruler of the Kingdom of the Isles, the Kingdom of Thomond, and perhaps the Kingdom of Dublin as well. His father was Tadc, son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain, King of Munster, which meant that Domnall was a member of the Meic Taidc, a branch of the Uí Briain. Domnall's mother was Mór, daughter of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles, which may have given Domnall a stake to the kingship of the Isles.

Énna Mac Murchada, or Enna Mac Murchada, also known as Énna mac Donnchada, and Énna mac Donnchada mic Murchada, was a twelfth-century ruler of Uí Chennselaig, Leinster, and Dublin. Énna was a member of the Meic Murchada, a branch of the Uí Chennselaig dynasty that came to power in Leinster in the person of his paternal great-grandfather. Énna himself gained power following the death of his cousin Diarmait mac Énna. Throughout much of his reign, Énna acknowledged the overlordship of Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht, although he participated in a failed revolt against the latter in 1124 before making amends. When Énna died in 1126, Toirdelbach successfully took advantage of the resulting power vacuum.

Domnall mac Murchada, also known as Domnall mac Murchada meic Diarmata, was a leading late eleventh-century claimant to the Kingdom of Leinster, and a King of Dublin. As a son of Murchad mac Diarmata, King of Dublin and the Isles, Domnall was a grandson of Diarmait mac Máel na mBó, King of Leinster, and thus a member of the Uí Chennselaig. Domnall was also the first of the Meic Murchada, a branch of the Uí Chennselaig named after his father.

The Meic Torcaill, also known as the Meic Turcaill, the Mac Torcaill dynasty, the Mac Turcaill dynasty, and the Mac Turcaill family, were a leading Norse-Gaelic family in mediaeval Dublin. The kindred produced several eminent men and kings of Dublin before the Norman conquest of the kingdom in 1170. Afterwards the family fell from prominence, losing possession of their extensive lands in the region. In time the Meic Torcaill lost precedence to other Dublin families, such as the Harolds and Archbolds.

Mac Scelling, also known as Mac Scilling, was a prominent twelfth-century military commander engaged in conflicts throughout Ireland. He is first recorded in 1154 commanding the maritime forces of Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, king of the Cenél nEógain, in a bloody encounter against Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair, king of Connacht. Muirchertach's naval forces were drawn from the western peripheries of Scotland and the Isles. He next appears on record in 1173/1174, supporting the cause of Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, king of Connacht against the English colonisation of Mide. An early modern Scottish source claims that a man of the same name was a bastard son of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, king of the Isles. If Mac Scelling was indeed related to Somairle, this relationship could cast light on the latter's conflict with the subsequent king, Guðrøðr Óláfsson, a man who appears to have opposed Muirchertach at some point in his career. Although not termed so in contemporary sources, Mac Scelling may be regarded as an early archetype of later gallowglasses, heavily-armed Scottish mercenaries recruited by Irish rulers in centuries that followed.

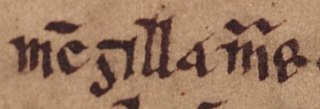

Ragnall Mac Gilla Muire was a twelfth-century leading figure of Waterford. He was one of several men taken prisoner by the English in 1170, when Waterford was captured by Richard de Clare. Ragnall is noted by a fourteenth-century legal enquiry which sought to determine whether a slain man was an Ostman—and thus entitled to English law—or an Irishman. Ragnall may the eponym of Reginald's Tower.