The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, usually known as the Basel Convention, is an international treaty that was designed to reduce the movements of hazardous waste between nations, and specifically to restrict the transfer of hazardous waste from developed to less developed countries. It does not address the movement of radioactive waste, controlled by the International Atomic Energy Agency. The Basel Convention is also intended to minimize the rate and toxicity of wastes generated, to ensure their environmentally sound management as closely as possible to the source of generation, and to assist developing countries in environmentally sound management of the hazardous and other wastes they generate.

Hazardous waste is waste that must be handled properly to avoid damaging human health or the environment. Waste can be hazardous because it is toxic, reacts violently with other chemicals, or is corrosive, among other traits. As of 2022, humanity produces 300-500 million metric tons of hazardous waste annually. Some common examples are electronics, batteries, and paints. An important aspect of managing hazardous waste is safe disposal. Hazardous waste can be stored in hazardous waste landfills, burned, or recycled into something new. Managing hazardous waste is important to achieve worldwide sustainability. Hazardous waste is regulated on national scale by national governments as well as on an international scale by the United Nations (UN) and international treaties.

The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter 1972, commonly called the "London Convention" or "LC '72" and also abbreviated as Marine Dumping, is an agreement to control pollution of the sea by dumping and to encourage regional agreements supplementary to the convention. It covers the deliberate disposal at sea of wastes or other matter from vessels, aircraft, and platforms. It does not cover discharges from land-based sources such as pipes and outfalls, wastes generated incidental to normal operation of vessels, or placement of materials for purposes other than mere disposal, providing such disposal is not contrary to aims of the convention. It entered into force in 1975. As of September 2016, there were 89 Parties to the convention.

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants is an international environmental treaty, signed on 22 May 2001 in Stockholm and effective from 17 May 2004, that aims to eliminate or restrict the production and use of persistent organic pollutants (POPs).

Ship breaking is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships either as a source of parts, which can be sold for re-use, or for the extraction of raw materials, chiefly scrap. Modern ships have a lifespan of 25 to 30 years before corrosion, metal fatigue and a lack of parts render them uneconomical to operate. Ship-breaking allows the materials from the ship, especially steel, to be recycled and made into new products. This lowers the demand for mined iron ore and reduces energy use in the steelmaking process. Fixtures and other equipment on board the vessels can also be reused. While ship-breaking is sustainable, there are concerns about its use by poorer countries without stringent environmental legislation. It is also labour-intensive, and considered one of the world's most dangerous industries.

Environmental harmful product dumping is the practice of transfrontier shipment of waste from one country to another. The goal is to take the waste to a country that has less strict environmental laws, or environmental laws that are not strictly enforced. The economic benefit of this practice is cheap disposal or recycling of waste without the economic regulations of the original country.

Methoxychlor is a synthetic organochloride insecticide, now obsolete. Tradenames for methoxychlor include Chemform, Maralate, Methoxo, Methoxcide, Metox, and Moxie.

The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, also known as the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) or the Bonn Convention, is an international agreement that aims to conserve migratory species throughout their ranges. The agreement was signed under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme and is concerned with conservation of wildlife and habitats on a global scale.

Bamako is the capital of Mali.

The Rotterdam Convention is a multilateral treaty to promote shared responsibilities in relation to importation of hazardous chemicals. The convention promotes open exchange of information and calls on exporters of hazardous chemicals to use proper labeling, include directions on safe handling, and inform purchasers of any known restrictions or bans. Signatory nations can decide whether to allow or ban the importation of chemicals listed in the treaty, and exporting countries are obliged to make sure that producers within their jurisdiction comply.

Under United States environmental policy, hazardous waste is a waste that has the potential to:

The regulation of chemicals is the legislative intent of a variety of national laws or international initiatives such as agreements, strategies or conventions. These international initiatives define the policy of further regulations to be implemented locally as well as exposure or emission limits. Often, regulatory agencies oversee the enforcement of these laws.

Waste management laws govern the transport, treatment, storage, and disposal of all manner of waste, including municipal solid waste, hazardous waste, and nuclear waste, among many other types. Waste laws are generally designed to minimize or eliminate the uncontrolled dispersal of waste materials into the environment in a manner that may cause ecological or biological harm, and include laws designed to reduce the generation of waste and promote or mandate waste recycling. Regulatory efforts include identifying and categorizing waste types and mandating transport, treatment, storage, and disposal practices.

Safe Planet: the United Nations Campaign for Responsibility on Hazardous Chemicals and Wastes is the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and UN Food and Agricultural Organization-led global public awareness and outreach campaign for ensuring the safety of human health and the environment against hazardous chemicals and wastes.

The Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement (日本・フィリピン経済連携協定) or in or commonly known as JPEPA is an economic partnership agreement concerning bilateral investment and free trade agreement between Japan and the Philippines. It was signed in Helsinki, Finland on September 9, 2006, by Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi and Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. It is the first bilateral trade treaty which the Philippines has entered since the Parity Right Agreement of 1946 with the United States. This treaty consists of 16 Chapters and 165 Articles, with 8 Annexes.

Toxic colonialism, or toxic waste colonialism, refers to the practice of exporting hazardous waste from developed countries to underdeveloped ones for disposal.

The global waste trade is the international trade of waste between countries for further treatment, disposal, or recycling. Toxic or hazardous wastes are often imported by developing countries from developed countries.

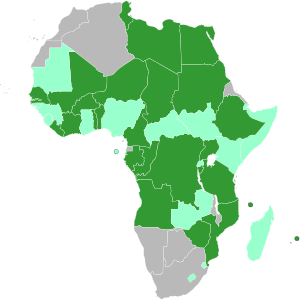

Electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) waste, or e-waste, is illegally brought into African states every year. A minimum of 250,000 metric tons of e-waste comes into the continent, and according to the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, the majority of it in West Africa enters from Europe. Developed countries commodify underdeveloped African states as dumping grounds for their e-waste, and due to poor regulations and a lack of enforcement institutions, illegal dumping is promoted. Currently, the largest e-waste dumping site in Africa is Agbogbloshie in Ghana. While states like Nigeria do not contain e-waste sites as concentrated as Agbogbloshie, they do have several small sites.