The Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive 2002/95/EC, short for Directive on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment, was adopted in February 2003 by the European Union.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is a strategy to add all of the estimated environmental costs associated with a product throughout the product life cycle to the market price of that product, contemporarily mainly applied in the field of waste management. Such societal costs are typically externalities to market mechanisms, with a common example being the impact of cars.

The presence of the logo on commercial products indicates that the manufacturer or importer affirms the goods' conformity with European health, safety, and environmental protection standards. It is not a quality indicator or a certification mark. The CE marking is required for goods sold in the European Economic Area (EEA); goods sold elsewhere may also carry the mark.

Electronic waste recycling, electronics recycling, or e-waste recycling is the disassembly and separation of components and raw materials of waste electronics; when referring to specific types of e-waste, the terms like computer recycling or mobile phone recycling may be used. Like other waste streams, reuse, donation, and repair are common sustainable ways to dispose of IT waste.

Type approval or certificate of conformity is granted to a product that meets a minimum set of regulatory, technical and safety requirements. Generally, type approval is required before a product is allowed to be sold in a particular country, so the requirements for a given product will vary around the world. Processes and certifications known as type approval in English are often called homologation, or some cognate expression, in other European languages.

An Electronic Waste Recycling Fee is a fee imposed by government on new purchases of electronic products. The fees are used to pay for the future recycling of these products, as many contain hazardous materials. Locations that have such fees include the European Union, the US State of California and the province of Ontario, Canada.

Electronic waste describes discarded electrical or electronic devices. It is also commonly known as waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) or end-of-life (EOL) electronics. Used electronics which are destined for refurbishment, reuse, resale, salvage recycling through material recovery, or disposal are also considered e-waste. Informal processing of e-waste in developing countries can lead to adverse human health effects and environmental pollution. The growing consumption of electronic goods due to the Digital Revolution and innovations in science and technology, such as bitcoin, has led to a global e-waste problem and hazard. The rapid exponential increase of e-waste is due to frequent new model releases and unnecessary purchases of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE), short innovation cycles and low recycling rates, and a drop in the average life span of computers.

The electronics industry is the economic sector that produces electronic devices. It emerged in the 20th century and is today one of the largest global industries. Contemporary society uses a vast array of electronic devices that are built in factories operated by the industry, which are almost always partially automated.

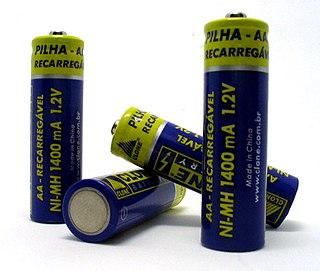

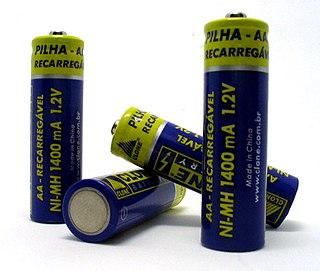

The Directive 2006/66/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 September 2006 on batteries and accumulators and waste batteries and accumulators and repealing Directive 91/157/EEC, commonly known as the Battery Directive, regulates the manufacture and disposal of batteries in the European Union with the aim of "improving the environmental performance of batteries and accumulators".

Rates of household recycling in Ireland have increased dramatically since the late 1990s. The Irish Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is the agency with overall responsibility for environmental protection in Ireland and monitors rates of recycling in Ireland along with other measures of environmental conditions in Ireland. The EPA, along with Repak, the principal organisation for packaging recycling in Ireland, report on recycling rates each year. In 2012 Ireland’s municipal solid waste (MSW) recycling rate was 34%, while the rate of packaging recycling reached 79%. The amount of municipal waste generated per person per year in Ireland has fallen significantly in recent years. This figure remains above the European Union annual municipal waste average of 503 kg per person, however. Each local council in Ireland has considerable control over recycling, so recycling practices vary to some extent across the country. Most waste that is not recycled is disposed of in landfill sites.

The Electronic Waste Recycling Act of 2003 (EWRA) is a California law to reduce the use of certain hazardous substances in certain electronic products sold in the state. The act was signed into law September 2003.

In 2015, 43.5% of the United Kingdom's municipal waste was recycled, composted or broken down by anaerobic digestion. The majority of recycling undertaken in the United Kingdom is done by statutory authorities, although commercial and industrial waste is chiefly processed by private companies. Local Authorities are responsible for the collection of municipal waste and operate contracts which are usually kerbside collection schemes. The Household Waste Recycling Act 2003 required local authorities in England to provide every household with a separate collection of at least two types of recyclable materials by 2010. Recycling policy is devolved to the administrations of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales who set their own targets, but all statistics are reported to Eurostat.

China RoHS, officially known as Administrative Measure on the Control of Pollution Caused by Electronic Information Products is a Chinese government regulation to control certain materials, including lead. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) of China is responsible for approval and publication of China's RoHS regulations.

The End of Life Vehicles Directive is a Directive of the European Union addressing the end of life for automotive products. Every year, motor vehicles which have reached the end of their useful lives create between 8 and 9 million tonnes of waste in the European Union. In 1997, the European Commission adopted a Proposal for a Directive to tackle this problem.

In a similar vein to packaging, electronic equipment and vehicles, the concept of extended producer responsibility was applied to battery regulations in the UK through the transposition of the EU Battery Directive into UK legislation. The Directive required member states to have put regulations in place by 26 September 2008. Although the UK managed to introduce the single market requirements by that date, they failed to implement the collection and recycling requirements. Following a consultation, the government laid the new Regulations before Parliament on 16 April 2009, which came into force on 5 May 2009. Responsibility for the financing of waste battery collection and treatment was applied to producers from 1 January 2010, whilst retailers were obliged to offer free take back of portable batteries to consumers from 1 February 2010.

Electronic waste is a significant part of today's global, post-consumer waste stream. Efforts are being made to recycle and reduce this waste.

Waste management laws govern the transport, treatment, storage, and disposal of all manner of waste, including municipal solid waste, hazardous waste, and nuclear waste, among many other types. Waste laws are generally designed to minimize or eliminate the uncontrolled dispersal of waste materials into the environment in a manner that may cause ecological or biological harm, and include laws designed to reduce the generation of waste and promote or mandate waste recycling. Regulatory efforts include identifying and categorizing waste types and mandating transport, treatment, storage, and disposal practices.

Appliance recycling is the process of dismantling scrapped home appliances to recover their parts or materials for reuse. Recycling appliances for their original or other purposes, involves disassembly, removal of hazardous components and destruction of the equipment to recover materials, generally by shredding, sorting and grading. The rate at which appliances are discarded has increased due in part to obsolescence due to technological advancement, and in part to not being designed to be repairable. The main types of appliances that are recycled are televisions, refrigerators, air conditioners, washing machines, and computers. When appliances are recycled, they can be looked upon as a valuable resources; if disposed of improperly, they can be environmentally harmful and poison ecosystems.