Related Research Articles

Aristotle was an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science.

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to create a likeness or an analogy.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse (trivium) along with grammar and logic/dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or writers use to inform, persuade, and motivate their audiences. Rhetoric also provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing arguments for particular situations.

The Western canon is the body of high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly valued in the West; works that have achieved the status of classics. However, not all these works originate in the Western world, and such works are also valued throughout the globe. It is "a certain Western intellectual tradition that goes from, say, Socrates to Wittgenstein in philosophy, and from Homer to James Joyce in literature".

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, moral philosophy, social philosophy, and interdisciplinary themes relevant to how people interpret meaning. In the humanities in modern academia, the latter style of literary scholarship is an offshoot of post-structuralism. Consequently, the word theory became an umbrella term for scholarly approaches to reading texts, some of which are informed by strands of semiotics, cultural studies, philosophy of language, and continental philosophy.

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature's goals and methods. Although the two activities are closely related, literary critics are not always, and have not always been, theorists.

Aristotle's Poetics is the earliest surviving work of Greek dramatic theory and the first extant philosophical treatise to focus on literary theory. In this text Aristotle offers an account of ποιητική, which refers to poetry and more literally "the poetic art," deriving from the term for "poet; author; maker," ποιητής. Aristotle divides the art of poetry into verse drama, lyric poetry, and epic. The genres all share the function of mimesis, or imitation of life, but differ in three ways that Aristotle describes:

- Differences in music rhythm, harmony, meter, and melody.

- Difference of goodness in the characters.

- Difference in how the narrative is presented: telling a story or acting it out.

New Criticism was a formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of literature functioned as a self-contained, self-referential aesthetic object. The movement derived its name from John Crowe Ransom's 1941 book The New Criticism.

Ivor Armstrong Richards CH, known as I. A. Richards, was an English educator, literary critic, poet, and rhetorician. His work contributed to the foundations of New Criticism, a formalist movement in literary theory which emphasized the close reading of a literary text, especially poetry, in an effort to discover how a work of literature functions as a self-contained and self-referential æsthetic object.

A literary genre is a category of literature. Genres may be determined by literary technique, tone, content, or length. They generally move from more abstract, encompassing classes, which are then further sub-divided into more concrete distinctions. The distinctions between genres and categories are flexible and loosely defined, and even the rules designating genres change over time and are fairly unstable.

Wayne Clayson Booth was an American literary critic and rhetorician. He was the George M. Pullman Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in English Language & Literature and the College at the University of Chicago. His work followed largely from the Chicago school of literary criticism.

Kenneth Duva Burke was an American literary theorist, as well as poet, essayist, and novelist, who wrote on 20th-century philosophy, aesthetics, criticism, and rhetorical theory. As a literary theorist, Burke was best known for his analyses based on the nature of knowledge. Further, he was one of the first individuals to stray from more traditional rhetoric and view literature as "symbolic action."

Aristotle's Rhetoric is an ancient Greek treatise on the art of persuasion, dating from the 4th century BCE. The English title varies: typically it is Rhetoric, the Art of Rhetoric, On Rhetoric, or a Treatise on Rhetoric.

Richard McKeon was an American philosopher and longtime professor at the University of Chicago. His ideas formed the basis for the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Ronald Salmon Crane was a literary critic, historian, bibliographer, and professor. He is credited with the founding of the Chicago School of Literary Criticism.

Poetics is the theory of structure, form, and discourse within literature, and, in particular, within poetry.

Neo-Aristotelianism is a view of literature and rhetorical criticism propagated by the Chicago School — Ronald S. Crane, Elder Olson, Richard McKeon, Wayne Booth, and others — which means:

"A view of literature and criticism which takes a pluralistic attitude toward the history of literature and seeks to view literary works and critical theories intrinsically."

Bartolomeo Maranta, also Bartholomaeus Marantha was an Italian physician, botanist, and literary theorist.

William Rea Keast was an American scholar and academic administrator who served as president of Wayne State University from 1965 to 1971.

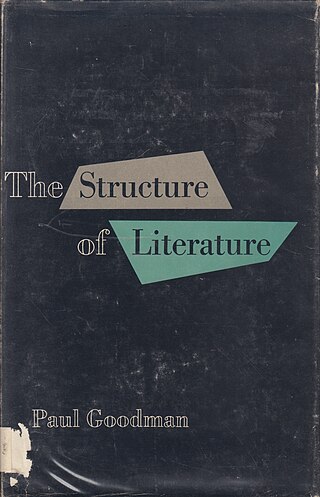

The Structure of Literature is a 1954 book of literary criticism by Paul Goodman, the published version of his doctoral dissertation in the humanities. The book proposes a mode of formal literary analysis that Goodman calls "inductive formal analysis": Goodman defines a formal structure within an isolated literary work, finds how parts of the work interact with each other to form a whole, and uses those definitions to study other works. Goodman analyzes multiple literary works as examples with close reading and genre discussion.

References

- ↑ Shrivastava, Ravindra (2004). Literary Criticism in Theory and Practice. Atlantic. p. 15. ISBN 9788126903290.

- ↑ Groarke, Lewis (1992). "Following in the Footsteps of Aristotle: The Chicago School, the Glue-Stick, and the Razor". Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 6 (3). Penn State University Press: 190–205. JSTOR 25670034 . Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ↑ Schneider, Anna-Dorothea (November 26, 2018). Humanities at the Crossroads: The Chicago Neo-Aristotelian Critics and the University of Chicago 1930 - 1950. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 211. ISBN 978-3848747702.

- Castle, Gregory. The Blackwell Guide to Literary Theory. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007

- Selden, Raman. A Reader's Guide to Contemporary Literary Theory. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993

- Wolfreys, Julian, ed. Modern North American Criticism and Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd., 2006

- Guerin, Wilfred L.; Labor, Earle; Lee, Morgan; Reesman, Jeanne C.; Willingham, John R. A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992

- Wellek, René. American Criticism, 1900-1950. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986. Vol. 6 of A History of Modern Criticism: 1750-1950

- Corman, Brian. “Chicago Critics” Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. Web page. 2005.