Delgamuukw v British Columbia, [1997] 3 SCR 1010, also known as Delgamuukw v The Queen, Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa, or simply Delgamuukw, is a ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada that contains its first comprehensive account of Aboriginal title in Canada. The Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en peoples claimed Aboriginal title and jurisdiction over 58,000 square kilometers in northwest British Columbia. The plaintiffs lost the case at trial, but the Supreme Court of Canada allowed the appeal in part and ordered a new trial because of deficiencies relating to the pleadings and treatment of evidence. In this decision, the Court went on to describe the "nature and scope" of the protection given to Aboriginal title under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, defined how a claimant can prove Aboriginal title, and clarified how the justification test from R v Sparrow applies when Aboriginal title is infringed. The decision is also important for its treatment of oral testimony as evidence of historic occupation.

Calder v British Columbia (AG) [1973] SCR 313, [1973] 4 WWR 1 was a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada. It was the first time that Canadian law acknowledged that aboriginal title to land existed prior to the colonization of the continent and was not merely derived from statutory law.

Kirkbi AG v. Ritvik Holdings Inc., popularly known as the Lego Case, is a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada. The Court upheld the constitutionality of section 7(b) of the Trade-marks Act which prohibits the use of confusing marks, as well, on a second issue it was held that the doctrine of functionality applied to unregistered trade-marks.

R v Pamajewon, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 821, is a leading Supreme Court of Canada decision on Aboriginal self-government under section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Court held that the right to self-government, if it exists, is subject to reasonable limitations and excluded the right to control high-stakes gambling.

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another colonising state. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, the content of aboriginal title, the methods of extinguishing aboriginal title, and the availability of compensation in the case of extinguishment vary significantly by jurisdiction. Nearly all jurisdictions are in agreement that aboriginal title is inalienable, and that it may be held either individually or collectively.

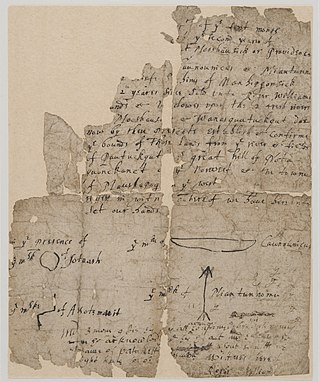

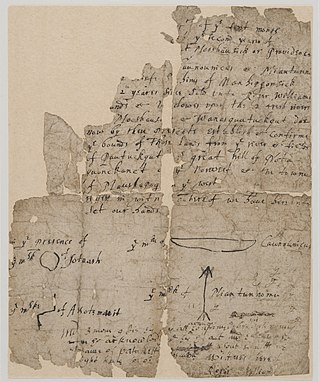

R v Marshall [1999] 3 S.C.R. 456 and R v Marshall [1999] 3 S.C.R. 533 are two decisions given by the Supreme Court of Canada on a single case regarding a treaty right to fish.

Whirlpool Corp v Camco Inc, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 1067; 2000 SCC 67, is a leading Supreme Court of Canada decision on patent claim construction and double patenting. The court adopted purposive construction as the means to construe patent claims. This judgement is to be read along with the related decision, Free World Trust v Électro Santé Inc, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 1066, 2000 SCC 66, where the Court articulated the scope of protection provided by patents.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

The Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act is a statute of the Parliament of Canada that allows insolvent corporations owing their creditors in excess of $5 million to restructure their businesses and financial affairs.

Once an invention is patented in Canada, exclusive rights are granted to the patent holder as defined by s.42 of the Patent Act. Any interference with the patent holder's "full enjoyment of the monopoly granted by the patent" is considered a patent infringement. Making, constructing, using, or selling a patented invention without the patent holder's permission can constitute infringement. Possession of a patented object, use of a patented object in a process, and inducement or procurement of an infringement may also, in some cases, count as infringement.

Sun Indalex Finance, LLC v United Steelworkers, 2013 SCC 6, arising from the Ontario courts as Re Indalex Limited, is a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada that deals with the question of priorities of claims in proceedings under the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act, and how they intersect with the fiduciary duties employers have as administrators of pension plans.

In Canada, trade secrets are generally considered to include information set out, contained or embodied in, but not limited to, a formula, pattern, plan, compilation, computer program, method, technique, process, product, device or mechanism; it may be information of any sort; an idea of a scientific nature, or of a literary nature, as long as they grant an economical advantage to the business and improve its value. Additionally, there must be some element of secrecy. Matters of public knowledge or of general knowledge in an industry cannot be the subject-matter of a trade secret.

Cinar Corp v Robinson is a leading case of the Supreme Court of Canada in the field of copyright law, which has impact in many key aspects of it, including:

Hryniak v Mauldin, 2014 SCC 7 is a landmark case of the Supreme Court of Canada that supports recent reforms to Canadian civil procedure in the area of granting summary judgment in civil cases.

Southcott Estates Inc v Toronto Catholic District School Board, 2012 SCC 51, [2012] 2 SCR 675, is a landmark case of the Supreme Court of Canada in the area of commercial law, with significant impact in the areas of:

Honda Canada Inc v Keays, 2008 SCC 39, [2008] 2 SCR 362 is a leading case of the Supreme Court of Canada that has had significant impact in Canadian employment law, in that it reformed the manner in which damages are to be awarded in cases of wrongful dismissal and it declared that such awards were not affected by the type of position an employee may have had.

Robert Patrick Armstrong is a Canadian lawyer and retired judge. He served on the Court of Appeal for Ontario from 2002 until his retirement in 2013. Before serving on the bench, Armstrong was a partner at Torys and was lead counsel in the Dubin Inquiry on steroid use in Canadian sports. After leaving the bench, Armstrong joined Arbitration Place, a Canadian group specializing in alternative dispute resolution.

Guindon v Canada, 2015 SCC 41 is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of Canada on the distinction between criminal and regulatory penalties, for the purposes of s.11 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It also provides guidance on when the Court will consider constitutional issues when such had not been argued in the lower courts.

Deloitte & Touche v Livent Inc , 2017 SCC 63 is a leading case of the Supreme Court of Canada concerning the duty of care that auditors have toward their clients during the course of a professional engagement.