Linear B is a syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examples dating to around 1400 BC. It is adapted from the earlier Linear A, an undeciphered script perhaps used for writing the Minoan language, as is the later Cypriot syllabary, which also recorded Greek. Linear B, found mainly in the palace archives at Knossos, Kydonia, Pylos, Thebes and Mycenae, disappeared with the fall of Mycenaean civilization during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The succeeding period, known as the Greek Dark Ages, provides no evidence of the use of writing.

Sir Arthur John Evans was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age.

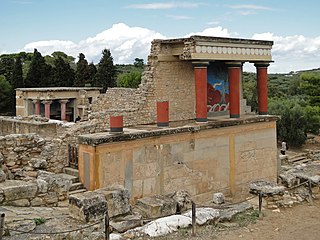

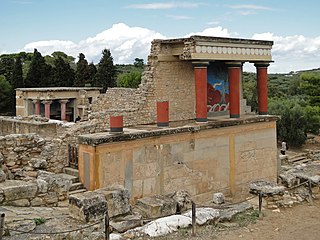

Knossos is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. The site was a major center of the Minoan civilization and is known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur. It is located on the outskirts of Heraklion, and remains a popular tourist destination. Knossos is considered by many to be the oldest city in Europe.

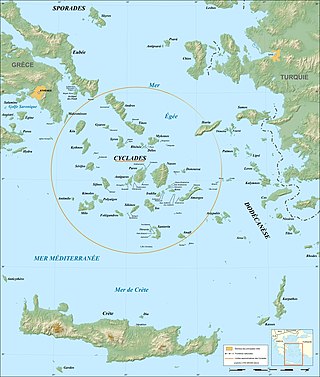

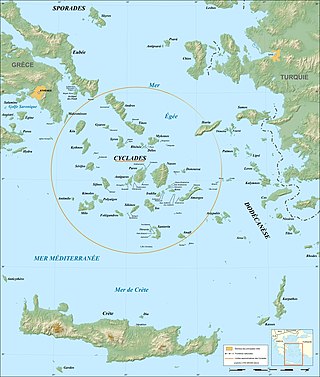

Cycladic culture was a Bronze Age culture found throughout the islands of the Cyclades in the Aegean Sea. In chronological terms, it is a relative dating system for artifacts which is roughly contemporary to Helladic chronology and Minoan chronology (Crete) during the same period of time.

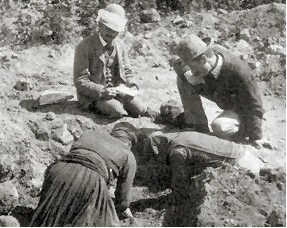

Spyridon Marinatos was a Greek archaeologist who specialised in the Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. He is best known for the excavation of the Minoan site of Akrotiri on Santorini, which he conducted between 1967 and 1974. A recipient of several honours in Greece and abroad, he was considered one of the most important Greek archaeologists of his day.

The British School at Athens is an institute for advanced research, one of the eight British International Research Institutes supported by the British Academy, that promotes the study of Greece in all its aspects. Under UK law it is a registered educational charity, which translates to a non-profit organisation in American and Greek law. It also is one of the 19 Foreign Archaeological Institutes defined by Hellenic Law No. 3028/2002, "On the Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in General," passed by the Greek Parliament in 2003. Under that law the 17 accredited foreign institutes may perform systematic excavation in Greece with the permission of the government.

John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury was a British archaeologist who worked for British intelligence during World War II. He was captured and summarily executed by German troops during the Battle of Crete.

Alan John Bayard Wace was an English archaeologist who served as director of the British School at Athens (BSA) between 1914 and 1923. He excavated widely in Thessaly, Laconia, and Egypt and at the Bronze Age site of Mycenae in Greece. He was also an authority on Greek textiles and a prolific collector of Greek embroidery.

Mycenaean pottery is the pottery tradition associated with the Mycenaean period in Ancient Greece. It encompassed a variety of styles and forms including the stirrup jar. The term "Mycenaean" comes from the site Mycenae, and was first applied by Heinrich Schliemann.

Arthur Alexander Johann Milchhöfer was a German archaeologist born in Schirwindt, East Prussia, Kingdom of Prussia. He specialized in studies of Greek Antiquity, and is remembered for his topographical research of ancient Attica.

Phylakopi, located at the northern coast of the island of Milos, is one of the most important Bronze Age settlements in the Aegean and especially in the Cyclades. The importance of Phylakopi is in its continuity throughout the Bronze Age and because of this, it is the type-site for the investigation of several chronological periods of the Aegean Bronze Age.

Knossos, also romanized Cnossus, Gnossus, and Knossus, is the main Bronze Age archaeological site at Heraklion, a modern port city on the north central coast of Crete. The site was excavated and the palace complex found there partially restored under the direction of Arthur Evans in the earliest years of the 20th century. The palace complex is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete. It was undoubtedly the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture.

Martin Sinclair Frankland Hood,, generally known as Sinclair Hood, was a British archaeologist and academic. He was Director of the British School at Athens from 1954 to 1962, and led the excavations at Knossos from 1957 to 1961. He turned 100 in January 2017 and died in January 2021, two weeks short of his 104th birthday.

Edith Eccles was a British classical archaeologist who did work at the British School at Athens and worked with Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos on Crete in the 1930s. She studied at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Nicoletta Momigliano is an archaeologist specialising in Minoan Crete and its modern reception.

Alexandre Farnoux is a French historian, a specialist on the Minoan civilisation and Delos.

Minos Kalokairinos was a Cretan Greek businessman and amateur archaeologist known for performing the first excavations at the Minoan palace of Knossos. His excavations were continued later by Arthur Evans.

Penelope Anne Mountjoy is an archaeologist from the United Kingdom who specializes in Mycenaean ceramics. Mountjoy has written several books and received numerous awards and fellowships to continue her research on Greek pottery.

Minoan snake tubes are cylindrical ceramic tubes with a closed, splayed out bottom. Sir Arthur Evans interpreted them as "snake tubes", that is vessels for carrying or housing snakes used in Minoan religion. They are now usually interpreted as "offering stands", on which kalathoi, or offering bowls, were placed in shrines. They are described as varying in material and construction despite sharing a common purpose. In the context of domestic shrines snake tubes are believed to have sat on top of or adjacent to a cult bench. In between the tubes would have been a goddess figurine and plaque which featured animal depictions.