This article needs additional citations for verification .(September 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Education in Andorra is mandatory for all children aged 6 to 16.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(September 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Education in Andorra is mandatory for all children aged 6 to 16.

There are essentially three coexisting school systems in the country: French, Spanish, and Andorran. [1] The French government partially subsidizes education in Andorra’s French-language schools; schools in the southern section, near Spain, are supported by the church. The local language, Catalan, has been introduced at a school under the control of the Roman Catholic Church. About 50% of Andorran children attend French primary schools, and the rest attend Spanish or Andorran schools. In general, Andorran schools follow the Spanish curriculum, and their diplomas are recognized by Spain. Primary school enrollment in 2003 was estimated at about 89%; 88% for boys and 90% for girls. The same year, secondary school enrollment was about 71%; 69% for boys and 74% for girls. The pupil to teacher ratio for primary school was at about 12:1 in 2003; the ratio was about 7:1 for secondary classes.[ citation needed ]

The University of Andorra was established in July 1997. [2] It has a small enrollment and mostly offers long-distance courses through universities in Spain and France. The majority of secondary graduates who continue their education attend schools in France or Spain. [1] In 2003, about 8% of eligible adult students were enrolled in tertiary programs. Virtually the entire adult population is literate. Andorra also has a nursing school and a school of computer science. [ citation needed ]

Education in Iran is centralized and divided into K-12 education plus higher education. Elementary and secondary education is supervised by the Ministry of Education and higher education is under supervision of Ministry of Science, research and Technology and Ministry of Health and Medical Education. As of September 2015, 93% of the Iranian adult population are literate. In 2008, 85% of the Iranian adult population were literate, well ahead of the regional average of 62%. This rate increases to 97% among young adults without any gender discrepancy. By 2007, Iran had a student to workforce population ratio of 10.2%, standing among the countries with highest ratio in the world.

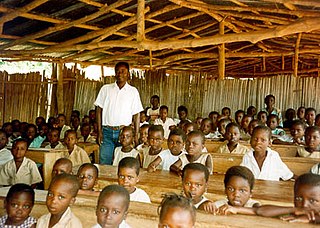

Cameroon is a Central African nation on the Gulf of Guinea. Bantu speakers were among the first groups to settle Cameroon, followed by the Muslim Fulani until German domination in 1884. After World War I, the French took over 80% of the area, and the British 20%. After World War II, self-government was granted, and in 1972, a unitary republic was formed out of East and West Cameroon. Until 1976 there were two separate education systems, French and English, which did not merge seamlessly. English is now considered the primary language of instruction. Local languages are generally not taught as there are too many, and choosing between them would raise further issues.

The system of education in Uganda has a structure of 7 years of primary education, 6 years of secondary education, and 3 to 5 years of post-secondary education, according to Education News Uganda The government of Uganda recognizes education as a basic human right and continues to strive to provide free primary education to all children in the country. However, issues with funding, teacher training, rural populations, and inadequate facilities continue to hinder the progress of educational development in Uganda. Girls in Uganda are disproportionately discriminated against in terms of education; they face harsher barriers when trying to gain an education and it has left the female population disenfranchised, despite government efforts to close the gap.

Education in Botswana is provided by public schools and private schools. Education in Botswana is governed by Ministry of Basic Education.

Education in Bulgaria is overseen by the Ministry of Education and Science. Since 2012, compulsory education includes two years of preschool education, before children start primary school. Education is compulsory until age of 16. Education at state-owned schools is free of charge, except for the higher education schools, colleges and universities.

The Government of Yemen has made the development of education system its top priority. The share of the budget dedicated to education has remained high during the past decade, averaging between 14 and 20% of the total government expenditure and as of 2000 it is 32.8 percent. The education expenditure is 9.6 percent of GDP for the year 2001 as seen in the chart below. In the strategic vision for the next 25 years since 2000,the government has committed to bring significant changes in the education system, thereby reducing illiteracy to less than 10% by 2025. Although Yemen's government provides for universal, compulsory, free education for children ages six through 15, the more U.S. Department of State reports that compulsory attendance is not enforced. The country ranked 150 out of 177 in the 2006 Human Development Index and 121 out of 140 countries in the Gender Development Index (2006). In 2005, 81 percent of Yemen's school-age population was enrolled in primary school; enrollment of the female population was 74 percent. Then in 2005, about 46 percent of the school-age population was enrolled in secondary school, including only 30 percent of eligible females. The country is still struggling to provide the requisite infrastructure. School facilities and educational materials are of poor quality, classrooms are too few in number, and the teaching faculty is inadequate.

Education in Ethiopia had been dominated by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church for many centuries until secular education was adopted in the early 1900s. Prior to 1974, Ethiopia had an estimated illiteracy rate well above 90% and compared poorly with the rest of Africa in the provision of schools and universities. After the Ethiopian Revolution, emphasis was placed on increasing literacy in rural areas. Practical subjects were stressed, as was the teaching of socialism. By 2015, the literacy rate had increased to 49.1%, still poor compared to most of the rest of Africa.

Education in Chad is challenging due to the nation's dispersed population and a certain degree of reluctance on the part of parents to send their children to school. Although attendance is compulsory, only 68% of boys continue their education past primary school, and over half of the population is illiterate. Higher education is provided at the University of N'Djamena.

Practically all children attend Quranic school for two or three years, starting around age five; there they learn the rudiments of the Islamic faith and some classical Arabic. When rural children attend these schools, they sometimes move away from home and help the teacher work his land.

Education in Mali is considered a fundamental right of Malians. For most of Mali's history, the government split primary education into two cycles which allowed Malian students to take examinations to gain admission to secondary, tertiary, or higher education. Mali has recently seen large increases in school enrollment due to educational reforms.

The education system in Morocco comprises pre-school, primary, secondary and tertiary levels. School education is supervised by the Ministry of National Education, with considerable devolution to the regional level. Higher education falls under the Ministry of Higher Education and Executive Training.

In 2005, the literacy rate in Laos was estimated to be 73%.

Education in Angola has four years of compulsory, free primary education which begins at age seven, and secondary education which begins at age eleven, lasting eight years. Basic adult literacy continues to be extremely low, but there are conflicting figures from government and other sources. It is difficult to assess literacy and education needs. Statistics available in 2001 from UNICEF estimated adult literacy to be 56 percent for males and 29 percent for women. On the other hand, the university system has been developing considerably over the last decade.

Education in Ivory Coast continues to face many challenges. The literacy rate for adults remains low: in 2000, it was estimated that only 48.7% of the total population was literate. Many children between 6 and 10 years are not enrolled in school, mainly children of poor families. The majority of students in secondary education are male. At the end of secondary education, students can sit the Baccalauréat examination. The country has universities in Abidjan, Bouaké, and Yamoussoukro.

This article is about education in Seychelles and its evolution from private mission schools to compulsory public education in the modern system.

Benin has abolished school fees and is carrying out the recommendations of its 2007 Educational Forum. In 1996, the gross primary enrollment rate was 72.5 percent, and the net primary enrollment rate was 59.3 percent. A far greater percentage of boys are enrolled in school than girls: In 1996, the gross primary enrollment rate for boys was 88.4 percent as opposed to 55.7 percent for girls. The net primary enrollment rates were 71.6 percent for boys and 46.2 percent for girls. Primary school attendance rates were unavailable for Benin as of 2001.

There have been major strides with Education in Equatorial Guinea over the past ten years, although there is still room for improvement. Education in Equatorial Guinea is overseen by the Ministry of Education and Science (MEC). Split into four levels, preschool, primary, secondary, and higher education, the Equatorial Guinea's educational system only deems preschool and primary school mandatory. Education in Equatorial Guinea is free and compulsory until the age of 14. Although it has a high GNI per capita, which, as of 2018, was 18,170 international dollars, its educational outcomes fall behind those of the rest of West and Central Africa. In 1993, the gross primary enrollment rate was 149.7 percent, and the net primary enrollment rate was 83.4 percent. Late entry into the school system and high dropout rates are common, and girls are more likely than boys to drop out of school. As of 2015, the net enrollment rates for each education level are as follows: 42 percent for preschool, between 60 percent and 86 percent for primary school, and 43.6 percent for secondary school. UNESCO has cited several issues with the current educational system, including poor nutrition, low quality of teachers, and lack of adequate facilities.

Education in Lesotho has undergone reforms in recent years, meaning that primary education is now free, universal, and compulsory.

Since gaining independence from France in 1956, the government of Tunisia has focused on developing an education system which produces a solid human capital base that could respond to the changing needs of a developing nation. Sustained structural reform efforts since the early 1990s, prudent macroeconomic policies, and deeper trade integration in the global economy have created an enabling environment for growth. This environment has been conducive to attain positive achievements in the education sector which placed Tunisia ahead of countries with similar income levels, and in a good position to achieve MDGs. According to the HDI 2007, Tunisia is ranked 90 out of 182 countries and is ranked 4th in MENA region just below Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan. Education is the number one priority of the government of Tunisia, with more than 20 percent of government’s budget allocated for education in 2005/06. As of 2006 the public education expenditure as a percentage of GDP stood at 7 percent.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Education in Andorra . |

| This Andorra-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |