Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes works in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin, Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

There are fifteen universities in Scotland and three other institutions of higher education that have the authority to award academic degrees.

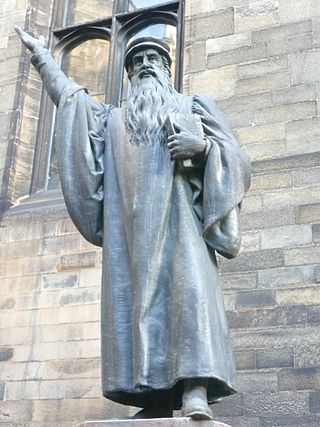

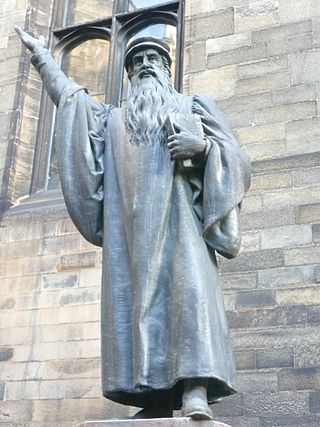

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

The history of education in Scotland in its modern sense of organised and institutional learning, began in the Middle Ages, when Church choir schools and grammar schools began educating boys. By the end of the 15th century schools were also being organised for girls and universities were founded at St Andrews, Glasgow and Aberdeen. Education was encouraged by the Education Act 1496, which made it compulsory for the sons of barons and freeholders of substance to attend the grammar schools, which in turn helped increase literacy among the upper classes.

Scottish society in the Middle Ages is the social organisation of what is now Scotland between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Social structure is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources. Kinship groups probably provided the primary system of organisation and society was probably divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare, a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes, above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

The Renaissance in Scotland was a cultural, intellectual and artistic movement in Scotland, from the late fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late fourteenth century and reaching northern Europe as a Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century. It involved an attempt to revive the principles of the classical era, including humanism, a spirit of scholarly enquiry, scepticism, and concepts of balance and proportion. Since the twentieth century, the uniqueness and unity of the Renaissance has been challenged by historians, but significant changes in Scotland can be seen to have taken place in education, intellectual life, literature, art, architecture, music, science and politics.

Music in early modern Scotland includes all forms of musical production in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. In this period the court followed the European trend for instrumental accompaniment and playing. Scottish monarchs of the sixteenth century were patrons of religious and secular music, and some were accomplished musicians. In the sixteenth century the playing of a musical instrument and singing became an expected accomplishment of noble men and women. The departure of James VI to rule in London at the Union of Crowns in 1603, meant that the Chapel Royal, Stirling Castle largely fell into disrepair and the major source of patronage was removed from the country. Important composers of the early sixteenth century included Robert Carver and David Peebles. The Lutheranism of the early Reformation was sympathetic to the incorporation of Catholic musical traditions and vernacular songs into worship, exemplified by The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567). However, the Calvinism that came to dominate Scottish Protestantism led to the closure of song schools, disbanding of choirs, removal of organs and the destruction of music books and manuscripts. An emphasis was placed on the Psalms, resulting in the production of a series of Psalters and the creation of a tradition of unaccompanied singing.

Education in early modern Scotland includes all forms of education within the modern borders of Scotland, between the end of the Middle Ages in the late fifteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century. By the sixteenth century such formal educational institutions as grammar schools, petty schools and sewing schools for girls were established in Scotland, while children of the nobility often studied under private tutors. Scotland had three universities, but the curriculum was limited and Scottish scholars had to go abroad to gain second degrees. These contacts were one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of Humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life. Humanist concern with education and Latin culminated in the Education Act 1496.

Scottish literature in the Middle Ages is literature written in Scotland, or by Scottish writers, between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century, until the establishment of the Renaissance in the late fifteenth century and early sixteenth century. It includes literature written in Brythonic, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, French and Latin.

Literature in early modern Scotland is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers between the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution in mid-eighteenth century. By the beginning of this era Gaelic had been in geographical decline for three centuries and had begun to be a second-class language, confined to the Highlands and Islands, but the traditions of Bard poetry in the Classical Gaelic literary language continued to survive. Middle Scots became the language of both the nobility and the majority population. The establishment of a printing press in 1507 made it easier to disseminate Scottish literature and was probably aimed at bolstering Scottish national identity.

Music in Medieval Scotland includes all forms of musical production in what is now Scotland between the fifth century and the adoption of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited. There are no major musical manuscripts for Scotland from before the twelfth century. There are occasional indications that there was a flourishing musical culture. Instruments included the cithara, tympanum, and chorus. Visual representations and written sources demonstrate the existence of harps in the Early Middle Ages and bagpipes and pipe organs in the Late Middle Ages. As in Ireland, there were probably filidh in Scotland, who acted as poets, musicians and historians. After this "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court in the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Scottish Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century.

Church music in Scotland includes all musical composition and performance of music in the context of Christian worship in Scotland, from the beginnings of Christianisation in the fifth century, to the present day. The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited due to factors including a turbulent political history, the destructive practices of the Scottish Reformation, the climate and the relatively late arrival of music printing. In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by monophonic plainchant, which led to the development of a distinct form of liturgical Celtic chant. It was superseded from the eleventh century by more complex Gregorian chant. In the High Middle Ages, the need for large numbers of singing priests to fulfill the obligations of church services led to the foundation of a system of song schools, to train boys as choristers and priests. From the thirteenth century, Scottish church music was increasingly influenced by continental developments. Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova consisting of complex polyphony. Survivals of works from the first half of the sixteenth century indicate the quality and scope of music that was undertaken at the end of the Medieval period. The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver, who produced complex polyphonic music.

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the Kingdom of Scotland. It emerged in the tenth century and continued until it ceased to function when James VI inherited the throne of England in 1603. For most of the medieval era, the king had no "capital" as such. The Pictish centre of Forteviot was the chief royal seat of the early Gaelic Kingdom of Alba that became the Kingdom of Scotland. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Scone was a centre for royal business. Edinburgh only began to emerge as the capital in the reign of James III but his successors undertook occasional royal progress to a part of the kingdom. Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I when it began to take on a distinctly feudal character, with the major offices of the Steward, Chamberlain, Constable, Marischal and Lord Chancellor. By the early modern era the court consisted of leading nobles, office holders, ambassadors and supplicants who surrounded the king or queen. The Chancellor was now effectively the first minister of the kingdom and from the mid-sixteenth century he was the leading figure of the Privy Council.

Scottish education in the nineteenth century concerns all forms of education, including schools, universities and informal instruction, in Scotland in the nineteenth century. By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete system of parish schools, but it was undermined by the Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanisation. The Church of Scotland, the Free Church of Scotland and the Catholic church embarked on programmes of school building to fill in the gaps in provision, creating a fragmented system. Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday schools, mission schools, ragged schools, Bible societies and improvement classes. Scots played a major part in the development of teacher education with figures including William Watson, Thomas Guthrie, Andrew Bell, John Wood and David Stow. Scottish schoolmasters gained a reputation for strictness and frequent use of the tawse. The perceived problems and fragmentation of the Scottish school system led to a process of secularisation, as the state took increasing control. The Education (Scotland) Act 1872 transferred the Kirk and Free Kirk schools to regional School Boards and made some provision for secondary education. In 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded, national system of compulsory free basic education with common examinations.

The history of universities in Scotland includes the development of all universities and university colleges in Scotland, between their foundation between the fifteenth century and the present day. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, or to the Continent. This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by Henry Wardlaw, bishop of St. Andrews. St Salvator's College was added to St. Andrews in 1450. The other great bishoprics followed, with the University of Glasgow being founded in 1451 and King's College, Aberdeen in 1495. Initially, these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen. International contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life in the sixteenth century.

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion, between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism and there is evidence of the worship of spirits and wells. The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England, from the sixth century. Elements of paganism survived into the Christian era. The earliest evidence of religious practice is heavily biased toward monastic life. Priests carried out baptisms, masses and burials, prayed for the dead and offered sermons. The church dictated moral and legal matters and impinged on other elements of everyday life through its rules on fasting, diet, the slaughter of animals and rules on purity and ritual cleansing. One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the Cult of Saints, with shrines devoted to local and national figures, including St Andrew, and the establishment of pilgrimage routes. Scots also played a major role in the Crusades. Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in the late medieval period. In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of mendicant orders of friars in the later fifteenth century. As the doctrine of Purgatory gained importance the number of chapelries, priests and masses for the dead within parish churches grew rapidly. New "international" cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary began to reach Scotland in the fifteenth century. Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century, but did not achieve a significant following.

The history of schools in Scotland includes the development of all schools as institutions and buildings in Scotland, from the early Middle Ages to the present day. From the early Middle Ages there were bardic schools, that trained individuals in the poetic and musical arts. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools. In the High Middle Ages, new sources of education arose including choir and grammar schools designed to train priests. Benedictine and Augustinian foundations probably had charitable almonry schools to educate young boys, who might enter the priesthood. Some abbeys opened their doors to teach the sons of gentlemen. By the end of the Middle Ages, grammar schools could be found in all the main burghs and some small towns. In rural areas there were petty or reading schools that provided an elementary education. Private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers sometimes developed into "household schools". Girls of noble families were taught in nunneries and by the end of the fifteenth century Edinburgh also had schools for girls, sometimes described as "sewing schools". There is documentary evidence for about 100 schools of these different kinds before the Reformation. The growing humanist-inspired emphasis on education cumulated with the passing of the Education Act 1496.

Scottish education in the eighteenth century concerns all forms of education, including schools, universities and informal instruction, in Scotland in the eighteenth century.

Childhood in Medieval Scotland includes all aspects of childhood within the geographical area that became the Kingdom of Scotland, from the end of Roman power in Great Britain, until the Renaissance and Reformation in the sixteenth century.