Thomas Caverhill Jerdon was an English physician, zoologist and botanist. He was a pioneering ornithologist who described numerous species of birds in India. Several species of plants and birds including Jerdon's baza, Jerdon's leafbird, Jerdon's bushlark, Jerdon's nightjar, Jerdon's courser, Jerdon's babbler and Jerdon's bush chat are named after him.

George Uglow Pope, or G. U. Pope, was an Anglican Christian missionary and Tamil scholar who spent 40 years in Tamil Nadu and translated many Tamil texts into English. His popular translations included those of the Tirukkural and Thiruvasagam.

Sir Joseph Fayrer, 1st Baronet FRS FRSE FRCS FRCP KCSI LLD was a British physician who served as Surgeon General in India. He is noted for his writings on medicine, work on public health and his studies particularly on the treatment of snakebite, in India. He was also involved in official investigation on cholera, in which he did not accept the idea, proposed by Robert Koch, of germs as the cause of cholera.

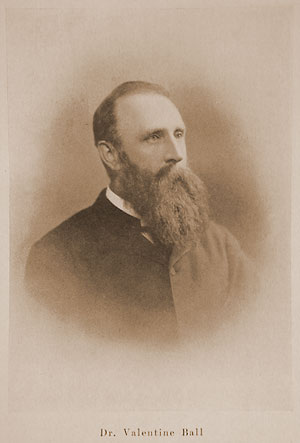

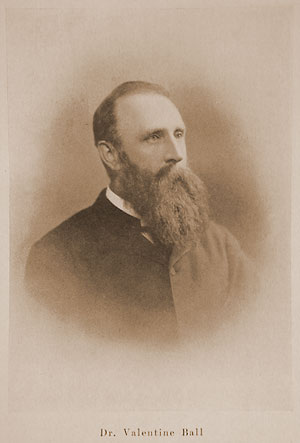

Valentine Ball was an Irish geologist, son of Robert Ball (1802–1857) and a brother of Sir Robert Ball. Ball worked in the Geological Survey of India for twenty years before returning to take up a position in Ireland.

Francis Talbot Day was an army surgeon and naturalist in the Madras Presidency who later became the Inspector-General of Fisheries in India and Burma. A pioneer ichthyologist, he described more than three hundred fishes in the two-volume work on The Fishes of India. He also wrote the fish volumes of the Fauna of British India series. He was also responsible for the introduction of trout into the Nilgiri hills, for which he received a medal from the French Societe d'Acclimatation. Many of his fish specimens are distributed across museums with only a small fraction deposited in the British Museum, an anomaly caused by a prolonged conflict with Albert Günther, the keeper of zoology there.

Thomas Michael Greenhow MD MRCS FRCS was an English surgeon and epidemiologist.

Members of the Scudder family have worked as medical missionaries in South India.

Hugh Francis Clarke Cleghorn was a Madras-born Scottish physician, botanist, forester and land owner. Sometimes known as the father of scientific forestry in India, he was the first Conservator of Forests for the Madras Presidency, and twice acted as Inspector General of Forests for India. After a career spent in India Cleghorn returned to Scotland in 1868, where he was involved in the first ever International Forestry Exhibition, advised the India Office on the training of forest officers, and contributed to the establishment of lectureships in botany at the University of St Andrews and in forestry at the University of Edinburgh. The plant genus Cleghornia was named after him by Robert Wight.

John Allan Broun FRS was a Scottish scientist with interests in magnetism, particularly of the earth, and meteorology. Broun studied in Edinburgh University and worked at the observatory in Makerstoun from 1842 to 1849 before moving to India to work in the Kingdom of Travancore. He continued his studies on geo-magnetism in India and was involved in setting up observatories there apart from managing the Napier Museum in Trivandrum. One of the fundamental discoveries he made was that the Earth loses or gains magnetic intensity not locally, but as a whole. He also found that solar activity causes magnetic disturbances.

William Robert Cornish was a British physician who served in India for more than thirty years, and became the Surgeon-General—head of medical services—in the Madras Presidency. During the Great Famine of 1876–78, Cornish, then Sanitary Commissioner of Madras, argued for generous famine relief, which put him at odds with Sir Richard Temple, Famine Envoy for the Government of India, who was promoting reduced rations. Some of Cornish's innovations made their way into the Indian Famine Codes of the late 19th century.

David Douglas Cunningham was a Scottish medical doctor and researcher who worked extensively in India on various aspects of public health and medicine. He studied the spread of bacteria and the spores of fungi through the air and conducted research on cholera. In his spare time he also studied the local plants and animals.

Sir Whitelaw Ainslie FRSE was a British surgeon and writer on materia medica, best known for his work as a surgeon in the employment of the East India Company in India. He published the first major English work on the medicinal plants of India in 1813.

Edmund Alexander Parkes was an English physician, known as a hygienist, particularly in the military context.

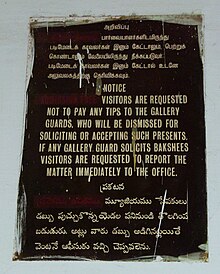

Surgeon General George BidieCIE was a British physician who worked in India in the Madras Medical Service. He was also Superintendent of the Government Museum, Chennai from 1872 to 1885.

Government Museum, Bangalore, established in 1865 by the Mysore State with the guidance of Surgeon Edward Balfour who founded the museum in Madras and supported by the Chief Commissioner of Mysore, L.B. Bowring, is one of the oldest museums in India and the second oldest museum in South India. It is now an archaeological museum and has a rare collection of archaeological and geological artifacts including old jewellery, sculpture, coins and inscriptions. The museum is also home to the Halmidi inscription, the earliest Kannada inscription.

Major General William Cullen was a British Army Officer with the Madras Artillery Regiment, and from 1840 to 1860, Resident in the Kingdom of Travancore and Cochin. During his stay in India, he took a scholarly interest in the region and contributed to journals on geology, plants and the culture of the region. He was instrumental in establishing the Napier Museum in Trivandrum. He died at Allepey in Kerala, where a road is named after him.

Samuel Browne or Brown was an English surgeon and botanist. He worked in the English East India Company factory at Fort St. George, Madras. Aside from his work he collected specimens of the local plants, especially grasses, along with vernacular names and made notes on their applications in medicine and other traditional use. He corresponded with several other contemporary naturalists including John Ray, Georg Joseph Kamel and James Petiver.

Alexander Hunter was a surgeon in the East India Company's Madras Army who was also a skilled and trained artist. In 1850 he founded the Madras School of Art, the first school of art and design in India, which was taken over by the government in 1855. He was a pioneer of photography in India, introduced courses at the art school, and founded the Madras Photographic Society. He was also a collector of geological specimens, a naturalist with interests in economic products, and a key organizer of the Madras Exhibitions of 1855 and 1857.

John Tricker Conquest was a British accoucheur (male-midwife) and physician who wrote an influential textbook on midwifery Outlines of Midwifery (1820) which went into several editions and was translated into many languages and promoted in colonial India.

John Shortt was an Anglo-Indian physician who served in the Madras Presidency in southern India. He conducted research on snake venoms, wrote on a variety of other subjects including anthropology, agriculture, and animal husbandry. A species of shieldtail snake endemic to the Shevaroy Hills is named after him, Uropeltis shorttii.