Hibbertopterus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Hibbertopterus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Devonian period in Belgium, Scotland and the United States to the Carboniferous period in Scotland, Ireland, the Czech Republic and South Africa. The type species, H. scouleri, was first named as a species of the significantly different Eurypterus by Samuel Hibbert in 1836. The generic name Hibbertopterus, coined more than a century later, combines his name and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing".

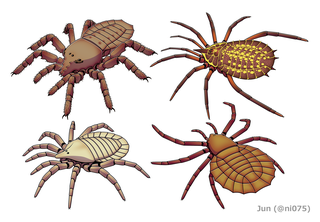

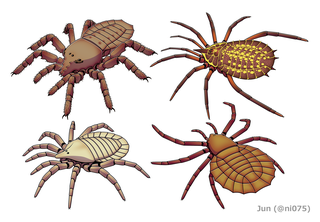

The order Trigonotarbida is a group of extinct arachnids whose fossil record extends from the late Silurian to the early Permian. These animals are known from several localities in Europe and North America, as well as a single record from Argentina. Trigonotarbids can be envisaged as spider-like arachnids, but without silk-producing spinnerets. They ranged in size from a few millimetres to a few centimetres in body length and had segmented abdomens (opisthosoma), with the dorsal exoskeleton (tergites) across the backs of the animals' abdomens, which were characteristically divided into three or five separate plates. Probably living as predators on other arthropods, some later trigonotarbid species were quite heavily armoured and protected themselves with spines and tubercles. About seventy species are currently known, with most fossils originating from the Carboniferous coal measures.

Phalangiotarbida is an extinct arachnid order first recorded from the Early Devonian of Germany and most widespread in the Upper Carboniferous coal measures of Europe and North America. The last species are known from the early Permian Rotliegend of Germany.

Palaeophonus is one of the oldest known genera of scorpions.

Euphoberia is an extinct genus of millipede from the Pennsylvanian epoch of the Late Carboniferous, measuring up to 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in length, that is small in Euphoberiidae which contains species with length about 30 centimetres (12 in). Fossils have been found in Europe and North America.

Campylocephalus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Campylocephalus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Carboniferous period in the Czech Republic to the Permian period of Russia. The generic name is composed of the Greek words καμπύλος (kampýlos), meaning "curved", and κεφαλή (kephalē), meaning "head".

Salteropterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Salteropterus have been discovered in deposits of Late Silurian age in Britain. Classified as part of the family Slimonidae, the genus contains one known valid species, S. abbreviatus, which is known from fossils discovered in Herefordshire, England, and a dubious species, S. longilabium, with fossils discovered in Leintwardine, also in Herefordshire. The generic name honours John William Salter, who originally described S. abbreviatus as a species of Eurypterus in 1859.

Eocarcinosoma is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. The type and only species of Eocarcinosoma, E. batrachophthalmus, is known from deposits of Late Ordovician age in the United States. The generic name is derived from the related genus Carcinosoma, and the Greek eós meaning 'dawn', referring to the earlier age of the genus compared to other carcinosomatid eurypterids.

Parahughmilleria is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Parahughmilleria have been discovered in deposits of the Devonian and Silurian age in the United States, Canada, Russia, Germany, Luxembourg and Great Britain, and have been referred to several different species. The first fossils of Parahughmilleria, discovered in the Shawangunk Mountains in 1907, were initially assigned to Eurypterus. It would not be until 54 years later when Parahughmilleria would be described.

Adelophthalmus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Adelophthalmus have been discovered in deposits ranging in age from the Early Devonian to the Early Permian, which makes it the longest lived of all known eurypterid genera, with a total temporal range of over 120 million years. Adelopththalmus was the final genus of the Eurypterina suborder of eurypterids and consisted the only known genus of swimming eurypterids from the Middle Devonian until its extinction during the Permian, after which the few surviving eurypterids were all walking forms of the suborder Stylonurina.

Euproops is an extinct genus of xiphosuran, related to the modern horseshoe crab. It lived during the Carboniferous Period.

Elonichthys is an extinct genus of prehistoric freshwater ray-finned fish known from the late Paleozoic. The genus sensu stricto contains three species known from the latest Carboniferous to the earliest Permian of freshwater ecosystems of Europe, but as a former wastebasket taxon, it contains many more dubiously-classified species from the Carboniferous and Permian of Europe, Greenland, South Africa, and North America.

Carcinosomatidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. They were members of the superfamily Carcinosomatoidea, also named after Carcinosoma. Fossils of carcinosomatids have been found in North America, Europe and Asia, the family possibly having achieved a worldwide distribution, and range in age from the Late Ordovician to the Early Devonian. They were among the most marine eurypterids, known almost entirely from marine environments.

Macroneuropteris is a genus of Carboniferous seed plants in the order Medullosales. The genus is best known for the species Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri, a medium-size tree that was common throughout the late Carboniferous Euramerica. Three similar species, M. macrophylla, M. britannica and M. subauriculata are also included in the genus.

Gigantoscorpio willsi is an extinct species of scorpion which lived between 345.0 million and 342.8 million years ago, during the Visean age of the Carboniferous. Its type specimen is BMNH In. 42706a,b, In. 42707, which is a 3D body fossil of its exoskeleton found near modern-day United Kingdom. It is thought to have grown up to around 40 cm (16 in) long, but later study estimated its total length about 24 cm (9.4 in).

Adelophthalmidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Adelophthalmidae is the only family classified as part of the superfamily Adelophthalmoidea, which in turn is classified within the infraorder Diploperculata in the suborder Eurypterina.

Eurypterina is one of two suborders of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Eurypterine eurypterids are sometimes informally known as "swimming eurypterids". They are known from fossil deposits worldwide, though primarily in North America and Europe.

This timeline of eurypterid research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of eurypterids, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods closely related to modern arachnids and horseshoe crabs that lived during the Paleozoic Era.

Weygoldtina is an extinct genus of tailless whip scorpion known from Carboniferous period, and the only known member of the family Weygoldtinidae. It is known from two species described from North America and England and originally described in the genus Graeophonus, which is now considered a nomen dubium.

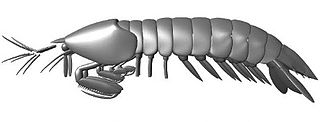

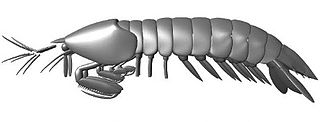

Tyrannophontes is an extinct genus of mantis shrimp that lived during the late Carboniferous period in what is now the Mazon Creek fossil beds of Illinois. It is the only genus in the family Tyrannophontidae. The type species, T. theridion, was described in 1969 by Frederick Schram. A second, much larger species, T. gigantion, was also named by Schram in 2007. Two other species were formerly assigned to the genus, but have since been reclassified.