George Bernard Shaw, known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 1880s to his death and beyond. He wrote more than sixty plays, including major works such as Man and Superman (1902), Pygmalion (1912) and Saint Joan (1923). With a range incorporating both contemporary satire and historical allegory, Shaw became the leading dramatist of his generation, and in 1925 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Back to Methuselah by George Bernard Shaw consists of a preface and a series of five plays: In the Beginning: B.C. 4004 , The Gospel of the Brothers Barnabas: Present Day, The Thing Happens: A.D. 2170, Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman: A.D. 3000, and As Far as Thought Can Reach: A.D. 31,920.

Saint Joan is a play by George Bernard Shaw about 15th-century French military figure Joan of Arc. Premiering in 1923, three years after her canonization by the Roman Catholic Church, the play reflects Shaw's belief that the people involved in Joan's trial acted according to what they thought was right. He wrote in his preface to the play:

There are no villains in the piece. Crime, like disease, is not interesting: it is something to be done away with by general consent, and that is all [there is] about it. It is what men do at their best, with good intentions, and what normal men and women find that they must and will do in spite of their intentions, that really concern us.

Charlotte Frances Payne-Townshend was an Irish political activist in Britain. She was a member of the Fabian Society and was dedicated to the struggle for women's rights. She married the playwright George Bernard Shaw.

How He Lied to Her Husband is a one-act comedy play by George Bernard Shaw, who wrote it, at the request of actor Arnold Daly, over a period of four days while he was vacationing in Scotland in 1904. In its preface he described it as "a sample of what can be done with even the most hackneyed stage framework by filling it in with an observed touch of actual humanity instead of with doctrinaire romanticism." The play has often been interpreted as a kind of satirical commentary on Shaw's own highly successful earlier play Candida.

Shakes versus Shav (1949) is a puppet play written by George Bernard Shaw. It was Shaw's last completed dramatic work. The play runs for 10 minutes in performance and comprises a comic argument between Shaw and Shakespeare, with the two playwrights bickering about who is the better writer as a form of intellectual equivalent of Punch and Judy.

Too True to Be Good (1932) is a comedy written by playwright George Bernard Shaw at the age of 76. Subtitled "A Collection of Stage Sermons by a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature", it moves from surreal allegory to the "stage sermons" in which characters discuss political, scientific and other developments of the day. The second act of the play contains a character based on Shaw's friend T. E. Lawrence.

A play is a work of drama, usually consisting mostly of dialogue between characters and intended for theatrical performance rather than just reading. The writer of a play is a playwright.

The Quintessence of Ibsenism is an essay written in 1891 by George Bernard Shaw, providing an extended analysis of the works of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen and of Ibsen's critical reception in England. By extension, Shaw uses this "exposition of Ibsenism" to illustrate the imperfections of British society, notably employing to that end an imaginary "community of a thousand persons," divided into three categories: Philistines, Idealists, and the lone Realist.

Village Wooing, A Comedietta for Two Voices is a play by George Bernard Shaw, written in 1933 and first performed in 1934. It has only two characters, hence the subtitle "a comedietta for two voices". The first scene takes place aboard a liner, the second in a village shop. The characters are known only as "A" and "Z".

The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet: A Sermon in Crude Melodrama is a one-act play by George Bernard Shaw, first produced in 1909. Shaw describes the play as a religious tract in dramatic form.

The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles: A Vision of Judgement is a 1934 play by George Bernard Shaw. The play is a satirical allegory about an attempt to create a utopian society on a Polynesian island that has recently emerged from the sea.

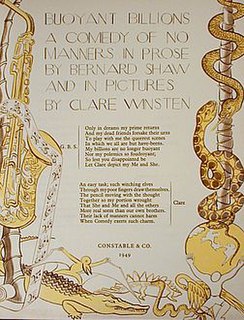

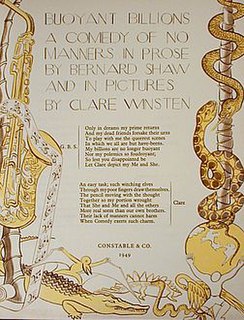

Buoyant Billions (1948) is a play by George Bernard Shaw. Written at the age of 92, it was his last full-length play. Subtitled "a comedy of no manners", the play is about a brash young man courting the daughter of an elderly billionaire, who is pondering how to dispose of his wealth after his death, a subject that was preoccupying Shaw himself at the time.

Why She Would Not: A Little Comedy (1950) is the last play written by George Bernard Shaw, comprising five short scenes. The play may or may not have been completed at his death. It was published six years later.

Geneva, a Fancied Page of History in Three Acts (1938) is a topical play by George Bernard Shaw. It describes a summit meeting designed to contain the increasingly dangerous behaviour of three dictators, Herr Battler, Signor Bombardone, and General Flanco.

Arthur and the Acetone (1936) is a satirical playlet by George Bernard Shaw which dramatises an imaginary conversation between the Zionist Chaim Weizmann and the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, which Shaw presents as the "true" story of how the Balfour Declaration came into being.

O'Flaherty V.C., A Recruiting Pamphlet (1915) is a comic one-act play written during World War I by George Bernard Shaw. The plot is about an Irish soldier in the British army returning home after winning the Victoria Cross. The play was written at a time when the British government was promoting recruitment in Ireland, while many Irish republicans expressed opposition to fighting in the war.

Overruled (1912) is a comic one-act play written by George Bernard Shaw. In Shaw's words, it is about "how polygamy occurs among quite ordinary people innocent of all unconventional views concerning it." The play concerns two couples who desire to switch partners, but are prevented from doing so by various considerations and end up negotiating an ambiguous set of relationships.

The Glimpse of Reality, A Tragedietta (1909) is a short play by George Bernard Shaw, set Italy during the 15th century. It is a parody of the verismo melodramas in vogue at the time. Shaw included it among what he called his "tomfooleries".

The Interlude at the Playhouse (1907) is a short comic sketch written by George Bernard Shaw to be delivered by Cyril Maude and his wife Winifred Emery as a curtain raiser at the opening of The Playhouse, a newly renovated theatre managed by Maude. The sketch was performed on Monday, 28 January, 1907.