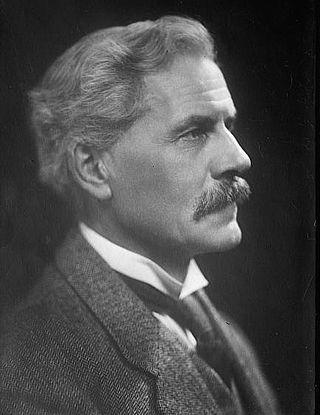

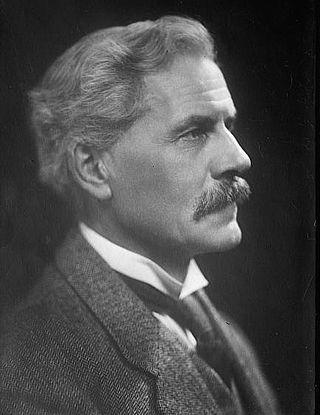

James Ramsay MacDonald was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 and again between 1929 and 1931. From 1931 to 1935, he headed a National Government dominated by the Conservative Party and supported by only a few Labour members. MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party as a result.

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member of parliament and later founded and led the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Diana, Lady Mosley was a British aristocrat, fascist, writer and editor. She was one of the Mitford sisters and eventually, the wife of Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists.

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, following the start of the Second World War, the party was proscribed by the British government and in 1940 it was disbanded.

William Richard Morris, 1st Viscount Nuffield, was an English motor manufacturer and philanthropist. He was the founder of Morris Motors Limited and is remembered as the founder of the Nuffield Foundation, the Nuffield Trust and Nuffield College, Oxford, as well as being involved in his role as President of BUPA in creating what is now Nuffield Health. He took his title from the village of Nuffield in Oxfordshire, where he lived.

The New Party was a political party briefly active in the United Kingdom in the early 1930s. It was formed by Sir Oswald Mosley, an MP who had belonged to both the Conservative and Labour parties, quitting Labour after its 1930 conference narrowly rejected his "Mosley Memorandum", a document he had written outlining how he would deal with the problem of unemployment.

The second MacDonald ministry was formed by Ramsay MacDonald on his reappointment as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by King George V on 5 June 1929. It was only the second time the Labour Party had formed a government; the First MacDonald Ministry held office in 1924.

Rotha Beryl Lintorn Lintorn-Orman was the founder of the British Fascisti, the first avowedly fascist movement to appear in British politics.

Thomas P. Moran was a leading member of the British Union of Fascists and a close associate of Oswald Mosley. Initially a miner, Moran later became a qualified engineer. He joined the Royal Air Force at 17 and later served in the Royal Naval Reserve as an engine room artificer.

Alexander Raven Thomson, usually referred to as Raven, was a Scottish politician and philosopher. He joined the British Union of Fascists in 1933 and remained a follower of Oswald Mosley for the rest of his life. Thomson was considered to be the party's chief ideologue and has been described as the "Alfred Rosenberg of British fascism".

Mosley was a 1998 television serial produced for Channel 4 based on British fascist Sir Oswald Mosley's life in the period between the two world wars. The series was directed by Robert Knights, from a screenplay by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran, both better known for their television comedy series. It was based on the books Rules of the Game and Beyond the Pale by Nicholas Mosley, Mosley's son.

Lady Cynthia Blanche Mosley, nicknamed "Cimmie", was a British aristocrat, politician and the first wife of the British Fascist politician Sir Oswald Mosley.

My Life is the autobiography of the British Fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley. It was published in 1968.

Robert Forgan was a British politician who was a close associate of Oswald Mosley.

British fascism is the form of fascism which is promoted by some political parties and movements in the United Kingdom. It is based on British ultranationalism and imperialism and had aspects of Italian fascism and Nazism both before and after World War II.

The Union Movement (UM) was a far-right political party founded in the United Kingdom by Oswald Mosley. Before the Second World War, Mosley's British Union of Fascists (BUF) had wanted to concentrate trade within the British Empire, but the Union Movement attempted to stress the importance of developing a European nationalism, rather than a narrower country-based nationalism. That has caused the UM to be characterised as an attempt by Mosley to start again in his political life by embracing more democratic and international policies than those with which he had previously been associated. The UM has been described as post-fascist by former members such as Robert Edwards, the founder of the pro-Mosley European Action, a British pressure group.

The British Fascists, formed in 1923, was the first political organisation in the United Kingdom to claim the label of fascist, although the group had little ideological unity apart from anti-socialism for much of its existence, and was strongly associated with conservatism. William Joyce, Neil Francis Hawkins, Maxwell Knight and Arnold Leese were amongst those to have passed through the movement as members and activists.

Henry Maxence Cavendish Drummond Wolff, commonly known as Henry Drummond Wolff, was a British Conservative Party politician. Drummond Wolff was known for his close ties to the far right.

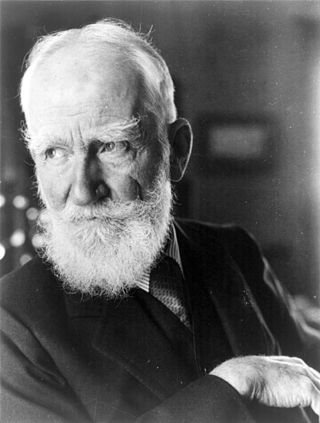

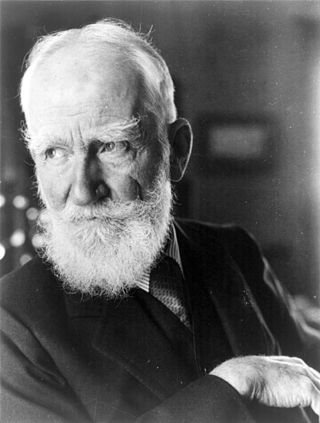

Press Cuttings (1909), subtitled A Topical Sketch Compiled from the Editorial and Correspondence Columns of the Daily Papers, is a play by George Bernard Shaw. It is a farcical comedy about the suffragettes' campaign for votes for women in Britain. The play is a departure from Shaw's earlier Ibsenesque dramas on social issues. Shaw's own pro-feminist views are never articulated by characters in the play, but instead it ridicules the arguments of the anti-suffrage campaigners.

The Battle of Carfax (1936) was a violent skirmish in the city of Oxford between the British Union of Fascists (BUF) and local anti-fascists, trade unionists, and supporters of the Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain. The battle took place inside Oxford's Carfax Assembly Rooms, a once popular meeting hall owned by Oxford City Council which was used for public events and located on Cornmarket Street.