Aedile was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order and duties to ensure the city of Rome was well supplied and its civil infrastructure well maintained, akin to modern local government.

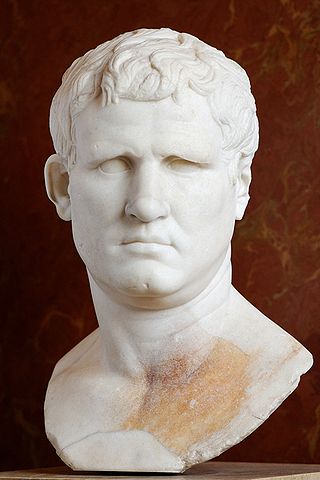

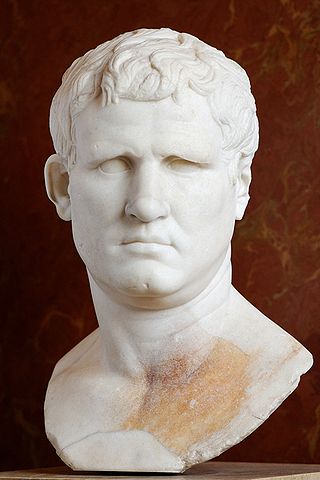

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa was a Roman general, statesman and architect who was a close friend, son-in-law and lieutenant to the Roman emperor Augustus. Agrippa is well known for his important military victories, notably the Battle of Actium in 31 BC against the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. He was also responsible for the construction of some of the most notable buildings of his era, including the original Pantheon.

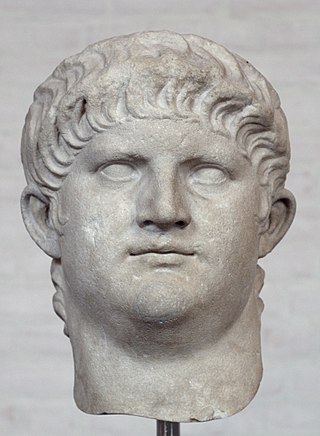

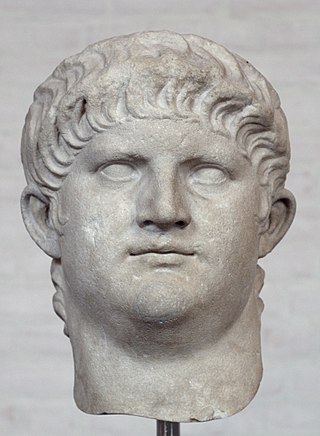

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his death in AD 68.

The Circus Maximus is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and largest stadium in ancient Rome and its later Empire. It measured 621 m (2,037 ft) in length and 118 m (387 ft) in width and could accommodate over 150,000 spectators. In its fully developed form, it became the model for circuses throughout the Roman Empire. The site is now a public park.

Gaius Plinius Secundus, known in English as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic Naturalis Historia, a comprehensive thirty-seven-volume work covering a vast array of topics on human knowledge and the natural world, which became an editorial model for encyclopedias. He spent most of his spare time studying, writing, and investigating natural and geographic phenomena in the field.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient Rome:

Nicomedia was an ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire, a status which the city maintained during the Tetrarchy system (293–324).

A fire department or fire brigade, also known as a fire company, fire authority, fire district, fire and rescue, or fire service in some areas, is an organization that provides fire prevention and fire suppression services as well as other rescue services.

The Domus Aurea was a vast landscaped complex built by the Emperor Nero largely on the Oppian Hill in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city.

The Great Fire of Rome began on the 18th of July 64 AD. The fire started in the merchant shops around Rome's chariot stadium, Circus Maximus. After six days, the fire was brought under control, but before the damage could be assessed, the fire reignited and burned for another three days. In the aftermath of the fire, 71% of Rome had been destroyed.

The vigintisexviri were a college (collegium) of minor magistrates in the Roman Republic. The college consisted of six boards:

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman civilisation from the founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic, and the Roman Empire until the fall of the western empire.

Firefighting is a profession aimed at controlling and extinguishing fire. A person who engages in firefighting is known as a firefighter or fireman. Firefighters typically undergo a high degree of technical training. This involves structural firefighting and wildland firefighting. Specialized training includes aircraft firefighting, shipboard firefighting, aerial firefighting, maritime firefighting, and proximity firefighting.

Vigiles or more properly the Vigiles Urbani or Cohortes Vigilum were the firefighters and police of ancient Rome.

The history of organized firefighting began in ancient Rome while under the rule of the first Roman Emperor Augustus. Prior to that, Ctesibius, a Greek citizen of Alexandria, developed the first fire pump in the third century BC, which was later improved upon in a design by Hero of Alexandria in the first century BC.

Ancient Romans with disabilities were recorded in the personal, medical, and legal writing of the period. While some disabled people were sought as slaves, others with disabilities that are now recognized by modern medicine were not considered disabled. Some disabilities were deemed more acceptable than others; while some were viewed as honorable characteristics or traits that increased morality, others, especially congenital conditions, resulted in infanticide. Rendering someone disabled was also used as a punishment. Some mobility aids, such as early prosthetics, have been documented. Small, scattered medical references contain the only direct acknowledgments of disability.

The praefectus vigilum was, starting with the reign of the Emperor Augustus, the commander of the city guards in Rome, whom were responsible for maintaining peace and order at night--a kind of fire and security police. Although less important than the other prefects, the office was considered a first step in order to reach an important position in the imperial administration.

The tresviri capitales or tresviri nocturni were one of the Vigintisexviri colleges in Ancient Rome. They were a group of three men that managed police and firefighting. Despite this they were feared by the Roman people due to their police roles, and they were condemned due to their neglect of firefighting during an unknown incident, which was likely the Great Fire of Rome. The Roman people gave the Tresviri Capitales the nickname nocturni due to the night patrols they managed. They were elected by the Urban praetors and later Tribal Assembly.

Marcus Egnatius Rufus was a Roman senator and politician at the time of Augustus.

In the Roman Republic, triumviri or tresviri were commissions of three men appointed for specific tasks. There were many tasks that commissions could be established to conduct, such as administer justice, mint coins, support religious tasks, or found colonies.