Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island near Charleston, South Carolina to defend the region from a naval invasion. It was built after British forces captured and occupied Washington during the War of 1812 via a naval attack. The fort was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle of Fort Sumter occurred, sparking the American Civil War. It was severely damaged during the battle and left in ruins. Although there were some efforts at reconstruction after the war, the fort as conceived was never completed. Since the middle of the 20th century, Fort Sumter has been open to the public as part of the Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park, operated by the National Park Service.

The Battle of Fort Pillow, also known as the Fort Pillow massacre, was fought on April 12, 1864, at Fort Pillow on the Mississippi River in Henning, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. The battle ended with Confederate soldiers commanded by Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest massacring U.S. Army soldiers attempting to surrender. Military historian David J. Eicher concluded: "Fort Pillow marked one of the bleakest, saddest events of American military history."

The Battle of Fort Stevens was an American Civil War battle fought July 11–12, 1864, in Washington County, D.C., during the Valley Campaigns of 1864 between forces under Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early and Union Major General Alexander McDowell McCook.

The Battle of Monocacy was fought on July 9, 1864, about 6 miles (9.7 km) from Frederick, Maryland, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 during the American Civil War. Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early defeated Union forces under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. The battle was part of Early's raid through the Shenandoah Valley and into Maryland in an attempt to divert Union forces from their siege of Gen. Robert E. Lee's army at Petersburg, Virginia.

Horatio Gouverneur Wright was an engineer and general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He took command of the VI Corps in May 1864 following the death of General John Sedgwick. In this capacity, he was responsible for building the fortifications around Washington DC, and in the Overland Campaign he commanded the first troops to break through the Confederate defenses at Petersburg. After the war, he was involved in a number of engineering projects, including the Brooklyn Bridge and the completion of the Washington Monument, and served as Chief of Engineers for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Second Battle of Fort Sumter was fought on September 8, 1863, in Charleston Harbor. Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard, who had commanded the defenses of Charleston and captured Fort Sumter in the first battle of the war, was in overall command of the defenders. In the battle, Union forces under Major General Quincy Gillmore attempted to retake the fort at the mouth of the harbor. Union gunners pummeled the fort from their batteries on Morris Island. After a severe bombing of the fort, Beauregard, suspecting an attack, replaced the artillerymen and all but one of the fort's guns with 320 infantrymen, who repulsed the naval landing party. Gillmore had reduced Fort Sumter to a pile of rubble, but the Confederate flag still waved over the ruins.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States, was the center of the Union war effort, which rapidly turned it from a small city into a major capital with full civic infrastructure and strong defenses.

Richmond, Virginia served as the capital of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War from May 8, 1861, hitherto the capital had been Montgomery, Alabama. Notwithstanding its political status, it was a vital source of weapons and supplies for the war effort, as well as the terminus of five railroads, and as such would have been defended by the Confederate States Army at all costs.

The city of Winchester, Virginia, and the surrounding area, were the site of numerous battles during the American Civil War, as contending armies strove to control the lower Shenandoah Valley. Winchester changed hands more often than any other Confederate city.

The 1st United States Sharpshooters were an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. During battle, the mission of the sharpshooter was to kill enemy targets of importance from long range.

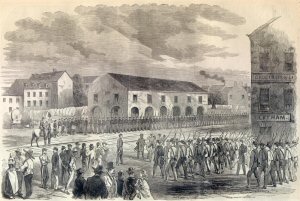

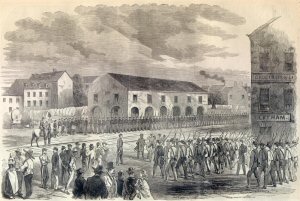

The 1st Michigan Sharpshooters Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army's Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War.

Fort Kearny was a fort constructed during the American Civil War as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. Located near Tenleytown, in the District of Columbia, it filled the gap between Fort Reno and Fort DeRussy north of the city of Washington. The fort was named in honor of Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny of the Union Army, who was killed at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862. Three batteries of guns supported the fort, and are considered part of the fort's defenses.

Daniel Davidson Bidwell was a civic leader in Buffalo, New York, before the outbreak of the American Civil War. He enlisted early in the war and then was appointed colonel of a regiment of infantry. He was promoted to general in command of a brigade in early 1864, leading it until he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Cedar Creek.

The 150th Ohio Infantry Regiment, sometimes 150th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Ulysses S. Grant was the most acclaimed Union general during the American Civil War and was twice elected president. Grant began his military career as a cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1839. After graduation he went on to serve with distinction as a lieutenant in the Mexican–American War. Grant was a keen observer of the war and learned battle strategies serving under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. After the war Grant served at various posts especially in the Pacific Northwest; he was forced to retire from the service in 1854 due to accusations of drunkenness. He was unable to make a success of farming and on the onset of the Civil War in April 1861, Grant was working as a clerk in his father's leather goods store in Galena, Illinois. When the war began his military experience was needed, and Congressman Elihu B. Washburne became his patron in political affairs and promotions in Illinois and nationwide.

Fort Totten Park is an American Civil War memorial on the site of a Union fort in Washington, DC. It is under the management of the National Park Service.

Fort Lincoln was one of seven temporary earthwork forts part of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, DC during the Civil War built in the Northeast quadrant of the city at the beginning of the Civil War by the Union Army to protect the city from the Confederate Army. From west to east, the forts were as follow: Fort Slocum, Fort Totten, Fort Slemmer, Fort Bunker Hill, Fort Saratoga, Fort Thayer and Fort Lincoln.

Fort Slocum was one of seven temporary earthwork forts, part of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, D.C., during the Civil War, built in the Northeast quadrant of the city after the beginning of the war by the Union Army to protect the city from the Confederate Army. From west to east, the forts were as follow: Fort Slocum, Fort Totten, Fort Slemmer, Fort Bunker Hill, Fort Saratoga, Fort Thayer and Fort Lincoln.

Rebecca McPherson Wright Bonsal was an American Quaker teacher who was fired for her Unionist loyalty. She delivered important intelligence to the Union Army during the American Civil War, which helped Union Generals Philip Sheridan and George Crook defeat Confederate General Jubal Early in the crucial Third Battle of Winchester in September, 1864.

James J. Purman was an American soldier who fought with the Union Army in the American Civil War. Purman received his country's highest award for bravery during combat, the Medal of Honor, for actions taken on July 2, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg.