The Battle of Fort Stevens was an American Civil War battle fought July 11–12, 1864, in Washington County, D.C. in present-day Northwest Washington, D.C., during the Valley campaigns of 1864 between forces under Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early and Union Major General Alexander McDowell McCook.

Horatio Gouverneur Wright was an engineer and general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He took command of the VI Corps in May 1864 following the death of General John Sedgwick. In this capacity, he was responsible for building the fortifications around Washington DC, and in the Overland Campaign he commanded the first troops to break through the Confederate defenses at Petersburg. After the war, he was involved in a number of engineering projects, including the Brooklyn Bridge and the completion of the Washington Monument, and served as Chief of Engineers for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The eastern theater of the American Civil War consisted of the major military and naval operations in the states of Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, the national capital in Washington, D.C., and the coastal fortifications and seaports of North Carolina. The interior of the Carolinas were considered part of the western theater, and other coastal areas along the Atlantic Ocean were part of the lower seaboard theater.

Fort Stevens, formerly named Fort Massachusetts, was part of the extensive fortifications built around Washington, D.C., during the American Civil War.

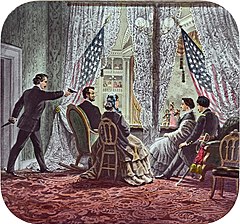

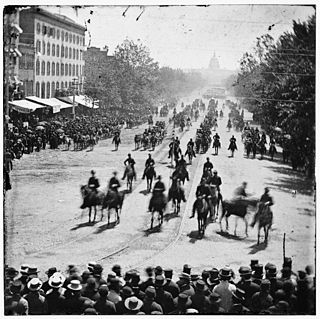

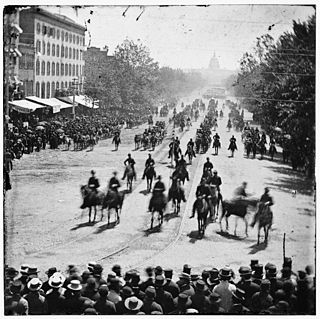

The Grand Review of the Armies was a military procession and celebration in the national capital city of Washington, D.C., on May 23–24, 1865, following the Union victory in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Elements of the Union Army in the United States Army paraded through the streets of the capital to receive accolades from the crowds and reviewing politicians, officials, and prominent citizens, including United States President Andrew Johnson, a month after the assassination of United States President Abraham Lincoln.

Fort Ward is a former Union Army installation now located in the city of Alexandria in the U.S. state of Virginia. It was the fifth largest fort built to defend Washington, D.C. in the American Civil War. It is currently well-preserved with 90-95% of its earthen walls intact.

Fort Reynolds was a Union Army redoubt built as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War.

Richmond, Virginia, served as the capital of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War from May 8, 1861, before that date the capital had been Montgomery, Alabama. Besides its political status, it was a vital source of weapons and supplies for the war effort, as well as the terminus of five railroads, and as such would have been defended by the Confederate States Army at all costs.

Charles Shiels Wainwright was a produce farmer in the state of New York and an artillery officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He played an important role in the defense of Cemetery Hill during the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, where his artillery helped repel a Confederate attack. His extensive diary kept during the war is considered to be among the finest such documents from the Civil War period.

The city of Winchester, Virginia, and the surrounding area, were the site of numerous battles during the American Civil War, as contending armies strove to control the lower Shenandoah Valley. Winchester changed hands more often than any other Confederate city.

Fort Stanton was a Civil War-era fortification constructed in the hills above Anacostia in the District of Columbia, USA, and was intended to prevent Confederate artillery from threatening the Washington Navy Yard. It also guarded the approach to the bridge that connected Anacostia with Washington. Built in 1861, the fort was expanded throughout the war and was joined by two subsidiary forts: Fort Ricketts and Fort Snyder. Following the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, it was dismantled and the land returned to its original owner. It never saw combat. Abandoned after the war, the site of the fort was planned to be part of a grand "Fort Circle" park system encircling the city of Washington. Though this system of interconnected parks never was fully implemented, the site of the fort is today a park maintained by the National Park Service, and a historical marker stands near the fort's original location.

Fort Bayard was an earthwork fort constructed in 1861 northwest of Tenleytown in the District of Columbia as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C., during the American Civil War. It never faced major opposition during the conflict and was decommissioned following the surrender of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Named after Brigadier General George Dashiell Bayard, who was killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg, the site of the fort is in Boundary Park, located at the intersection of River Road and Western Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and is maintained by the U.S. National Park Service. No trace of the fort remains, though a marker commemorating its existence has been erected by the Park Service.

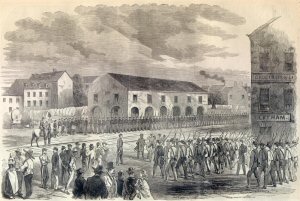

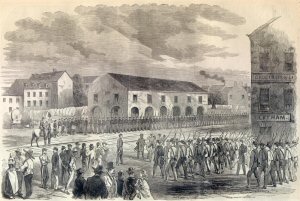

Fort Corcoran was a wood-and-earthwork fortification constructed by the Union Army in northern Virginia as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. during the American Civil War. Built in 1861, shortly after the occupation of Arlington, Virginia by Union forces, it protected the southern end of the Aqueduct Bridge and overlooked the Potomac River and Theodore Roosevelt Island, known as Mason's Island.

Fort Runyon was a timber and earthwork fort constructed by the Union Army following the occupation of northern Virginia in the American Civil War in order to defend the southern approaches to the Long Bridge as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. during that war. The Columbia Turnpike and Alexandria and Loudon Railroad ran through the pentagonal structure, which controlled access to Washington via the Long Bridge. With a perimeter of almost 1,500 yards (1,400 m), and due to its unusual shape it was approximately the same size, shape, and in almost the same location as the Pentagon, built 80 years later.

Fort Lyon was a timber and earthwork fortification constructed south of Alexandria, Virginia, as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. during the American Civil War. Built in the weeks following the Union defeat at Bull Run, Fort Lyon was situated on Ballenger's Hill south of Hunting Creek, and Cameron Run, near Mount Eagle. From its position on one of the highest points south of Alexandria, the fort overlooked Telegraph Road, the Columbia Turnpike, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, the Little River Turnpike, and the southern approaches to the city of Alexandria, the largest settlement in Union-occupied Northern Virginia.

Fort Willard is a former Union Army installation now located in the Belle Haven area of Fairfax County in the U.S. state of Virginia. It is currently undergoing preservation treatment to protect its earthen walls and trenches.

Fort O'Rourke is a former Union Army installation now located in the Belle Haven area of Fairfax County in the U.S. state of Virginia. It was the southernmost fort built to defend Washington, D.C. in the American Civil War.

Cyrus Ballou Comstock was a career officer in the Regular Army of the United States. After graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1855, Comstock served with the Army Corps of Engineers. At the beginning of the American Civil War, he assisted with the fortification of Washington, D.C. In 1862, he was transferred to the field, eventually becoming chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac. In 1863 during the Siege of Vicksburg, he served as the chief engineer of the Army of the Tennessee.

On the onset of the American Civil War in April 1861, Ulysses S. Grant was working as a clerk in his father's leather goods store in Galena, Illinois. When the war began, his military experience was needed, and congressman Elihu B. Washburne became his patron in political affairs and promotions in Illinois and nationwide.

Fort Farnsworth is a former Union Army installation now located in the Huntington area of Fairfax County, Virginia. It was a timber and earthwork fortification constructed south of Alexandria, Virginia as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. during the American Civil War. Nothing survives of the fort's structure as the Huntington Station of the Washington Metro occupies Fort Farnsworth's former hilltop site.