"Marching Through Georgia" is an American Civil War-era marching song written and composed by Henry Clay Work. It is sung from the perspective of a Union soldier who had participated in Sherman's March to the Sea; he looks back on the triumph after which Georgia became a "thoroughfare for freedom" and the Confederacy neared collapse.

Contents

- Background

- Work as a songwriter

- March to the Sea

- Composition

- Lyrical analysis

- Musical analysis

- General analysis

- Legacy

- Postwar

- Military and nationalist uses

- Political uses

- Other uses

- References

- Notes

- Citations

- Bibliography

- Books

- Studies and journals

- News articles

- Websites

- External links

- General

- Recordings

Work made a name for himself in the Civil War for penning songs that reflected the Union's struggle and progress in the war. The music publishing house Root & Cady employed him in 1861, a post he maintained throughout the war. Following the March to the Sea, the Union's triumph that left Confederate resources in tatters and civilians in anguish, Work was inspired to write a commemorative tune, "Marching Through Georgia".

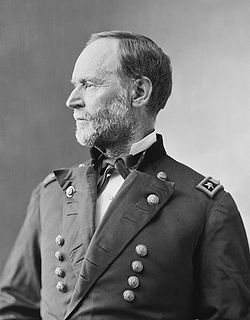

The song was released in January 1865 to widespread success. One of the few Civil War compositions that withstood the war's end, it cemented a place in veteran reunions and marching parades. Sherman, to whom the song is dedicated, grew to despise it after being repeatedly subjected to its strains at the public gatherings he attended. "Marching Through Georgia" lent its tune to numerous partisan hymns, such as "Billy Boys" and "The Land". Beyond the United States, troops across the world have adopted it as a marching standard, from the Japanese in the Russo–Japanese War to the British in World War Two.