| Louisiana | |

|---|---|

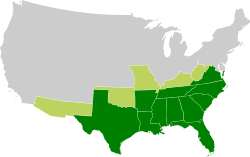

Map of the Confederate States | |

| Capital | Shreveport |

| Largest city | New Orleans |

| Admitted to the Confederacy | March 21, 1861 (3rd) |

| Population |

|

| Forces supplied | |

| Governor | Thomas Moore Henry Allen |

| Lieutenant Governor | |

| Senators | |

| Representatives | List |

| Restored to the Union | July 9, 1868 |

| History of Louisiana |

|---|

|

|

| Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

| Dual governments |

| Territory |

| Allied tribes in Indian Territory |

Louisiana was a dominant population center in the southwest of the Confederate States of America, controlling the wealthy trade center of New Orleans, and contributing the French Creole and Cajun populations to the demographic composition of a predominantly Anglo-American country. In the antebellum period, Louisiana was a slave state, where enslaved African Americans had comprised the majority of the population during the eighteenth-century French and Spanish dominations. By the time the United States acquired the territory (1803) and Louisiana became a state (1812), the institution of slavery was entrenched. By 1860, 47% of the state's population were enslaved, though the state also had one of the largest free black populations in the United States. Much of the white population, particularly in the cities, supported slavery, while pockets of support for the U.S. and its government existed in the more rural areas.

Contents

- Politics and strategy in Louisiana

- Secession

- Union plans

- Notable Civil War leaders from Louisiana

- Battles in Louisiana

- Restoration to Union

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- External links

Louisiana declared that it had seceded from the Union on January 26, 1861. Civil-War era New Orleans, the largest city in the South, was strategically important as a port city due to its southernmost location on the Mississippi River and its access to the Gulf of Mexico. The U.S. War Department early on planned for its capture. The city was taken by U.S. Army forces on April 25, 1862. Because a large part of the population had Union sympathies (or compatible commercial interests), the U.S. government took the unusual step of designating the areas of Louisiana then under U.S. control as a state within the Union, with its own elected representatives to the U.S. Congress. For the latter part of the war, both the U.S. and the Confederacy recognized their own distinct Louisiana governors. [4] : 1–9 Similarly, New Orleans and 13 named parishes of the state were exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, which applied exclusively to states in rebellion against the Union. [5]