Jewish holidays, also known as Jewish festivals or Yamim Tovim, are holidays observed by Jews throughout the Hebrew calendar. They include religious, cultural and national elements, derived from three sources: biblical mitzvot ("commandments"), rabbinic mandates, and the history of Judaism and the State of Israel.

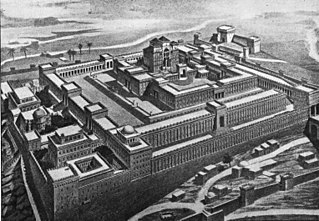

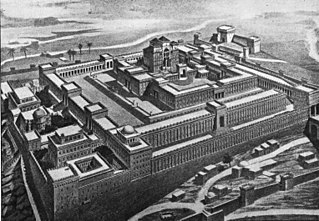

Sukkot is a Torah-commanded holiday celebrated for seven days, beginning on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei. It is one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals on which those Israelites who could were commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. In addition to its harvest roots, the holiday also holds spiritual importance with regard to its abandonment of materialism to focus on nationhood, spirituality, and hospitality, this principle underlying the construction of a temporary, almost nomadic, structure of a sukkah.

Shemini Atzeret is a Jewish holiday. It is celebrated on the 22nd day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei in the Land of Israel, and on the 22nd and 23rd outside the Land, usually coinciding with late September or early October. It directly follows the Jewish festival of Sukkot which is celebrated for seven days, and thus Shemini Atzeret is literally the eighth day. It is a separate—yet connected—holy day devoted to the spiritual aspects of the festival of Sukkot. Part of its duality as a holy day is that it is simultaneously considered to be both connected to Sukkot and also a separate festival in its own right.

Lulav is a closed frond of the date palm tree. It is one of the Four Species used during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. The other Species are the hadass (myrtle), aravah (willow), and etrog (citron). When bound together, the lulav, hadass, and aravah are commonly referred to as "the lulav".

Etrog is the yellow citron or Citrus medica used by Jews during the week-long holiday of Sukkot as one of the four species. Together with the lulav, hadass, and aravah, the etrog is taken in hand and held or waved during specific portions of the holiday prayers. Special care is often given to selecting an etrog for the performance of the Sukkot holiday rituals.

The Hebrew word for 'symbol' is ot, which, in early Judaism, denoted not only a sign, but also a visible religious token of the relation between God and human.

Moed is the second Order of the Mishnah, the first written recording of the Oral Torah of the Jewish people. Of the six orders of the Mishna, Moed is the third shortest. The order of Moed consists of 12 tractates:

- Shabbat: or Shabbath ("Sabbath") deals with the 39 prohibitions of "work" on the Shabbat. 24 chapters.

- Eruvin: (ערובין) ("Mixtures") deals with the Eruv or Sabbath-bound - a category of constructions/delineations that alter the domains of the Sabbath for carrying and travel. 10 chapters.

- Pesahim: (פסחים) deals with the prescriptions regarding the Passover and the paschal sacrifice. 10 chapters.

- Shekalim: (שקלים) ("Shekels") deals with the collection of the half-Shekel as well as the expenses and expenditure of the Temple. 8 chapters

- Yoma: (יומא) ; called also "Kippurim" or "Yom ha-Kippurim" ; deals with the prescriptions Yom Kippur, especially the ceremony by the Kohen Gadol. 8 chapters.

- Sukkah: (סוכה) ("Booth"); deals with the festival of Sukkot and the Sukkah itself. Also deals with the Four Species which are waved on Sukkot. 5 chapters.

- Beitza: (ביצה) ("Egg"); deals chiefly with the rules to be observed on Yom Tov. 5 chapters.

- Rosh Hashanah: deals chiefly with the regulation of the calendar by the new moon, and with the services of the festival of Rosh Hashanah. 4 chapters.

- Ta'anit: (תענית) ("Fasting") deals chiefly with the special fast-days in times of drought or other untoward occurrences. 4 chapters

- Megillah: (מגילה) ("Scroll") contains chiefly regulations and prescriptions regarding the reading of the scroll of Esther at Purim, and the reading of other passages from the Torah and Neviim in the synagogue. 4 chapters.

- Mo'ed Katan: deals with Chol HaMoed, the intermediate festival days of Pesach and Sukkot. 3 chapters.

- Hagigah: (חגיגה) deals with the Three Pilgrimage Festivals and the pilgrimage offering that men were supposed to bring in Jerusalem. 3 chapters.

Karaite Judaism or Karaism is a Jewish religious movement characterized by the recognition of the written Tanakh alone as its supreme authority in halakha and theology. Karaites believe that all of the divine commandments which were handed down to Moses by God were recorded in the written Torah without any additional Oral Law or explanation. Unlike mainstream Rabbinic Judaism, which regards the Oral Torah, codified in the Talmud and subsequent works, as authoritative interpretations of the Torah, Karaite Jews do not treat the written collections of the oral tradition in the Midrash or the Talmud as binding.

Hoshana Rabbah is the seventh day of the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, the 21st day of the month of Tishrei. This day is marked by a special synagogue service, the Hoshana Rabbah, in which seven circuits are made by the worshippers with their lulav and etrog, while the congregation recites Hoshanot. It is customary for the scrolls of the Torah to be removed from the ark during this procession. In a few communities a shofar is sounded after each circuit.

Daniel al-Kumisi was one of the most prominent early scholars of Karaite Judaism. He flourished at the end of the ninth or the beginning of the tenth century. He was a native of Damagan, capital of the province of Qumis in the former state of Tabaristan, as is shown by his two surnames, the latter of which is found only in Jacob Qirqisani's works.

Hadass is a branch of the myrtle tree that forms part of the lulav used on the Jewish holiday of Sukkot.

Aravah is a leafy branch of the willow tree. It is one of the Four Species used in a special waving ceremony during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. The other species are the lulav, hadass (myrtle), and etrog (citron).

Chol HaMoed, a Hebrew phrase meaning "mundane of the festival", refers to the intermediate days of Passover and Sukkot. As the name implies, these days mix features of chol (mundane) and moed (festival).

Emor is the 31st weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Leviticus. The parashah describes purity rules for priests, recounts the holy days, describes the preparations for the lights and bread in the sanctuary, and tells the story of a blasphemer and his punishment. The parashah constitutes Leviticus 21:1–24:23. It has the most verses of any of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Leviticus, and is made up of 6,106 Hebrew letters, 1,614 Hebrew words, 124 verses and 215 lines in a Torah Scroll.

Pinechas, Pinchas, Pinhas, or Pin'has is the 41st weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Numbers. It tells of Phinehas's killing of a couple, ending a plague, and of the daughters of Zelophehad's successful plea for land rights. It constitutes Numbers 25:10–30:1. The parashah is made up of 7,853 Hebrew letters, 1,887 Hebrew words, 168 verses, and 280 lines in a Torah scroll.

Re'eh, Reeh, R'eih, or Ree is the 47th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fourth in the Book of Deuteronomy. It comprises Deuteronomy 11:26–16:17. In the parashah, Moses set before the Israelites the choice between blessings and curses. Moses instructed the Israelites in laws that they were to observe, including the law of a single centralized place of worship. Moses warned against following other gods and their prophets and set forth the laws of kashrut, tithes, the Sabbatical year, the Hebrew slave, firstborn animals, and the Three Pilgrim Festivals.

Sukkah is a tractate of the Mishnah and Talmud. Its laws are discussed as well in the Tosefta and both the Babylonian Talmud and Jerusalem Talmud. In most editions it is the sixth volume of twelve in the Order of Moed. Sukkah deals primarily with laws relating to the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. It has five chapters.

A sukkah or succah is a temporary hut constructed for use during the week-long Jewish festival of Sukkot. It is topped with branches and often well decorated with autumnal, harvest or Judaic themes. The book of Vayikra (Leviticus) describes it as a symbolic wilderness shelter, commemorating the time God provided for the Israelites in the wilderness they inhabited after they were freed from slavery in Egypt. It is common for Jews to eat, sleep and otherwise spend time in the sukkah. In Judaism, Sukkot is considered a joyous occasion and is referred to in Hebrew as Z'man Simchateinu, and the sukkah itself symbolizes the fragility and transience of life and one's dependence on God.

The palm branch, or palm frond, is a symbol of victory, triumph, peace, and eternal life originating in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean world. The palm (Phoenix) was sacred in Mesopotamian religions, and in ancient Egypt represented immortality. In Judaism, the lulav, a closed frond of the date palm is part of the festival of Sukkot. A palm branch was awarded to victorious athletes in ancient Greece, and a palm frond or the tree itself is one of the most common attributes of Victory personified in ancient Rome.

The Yemenite citron is a variety of citron, usually containing no juice vesicles in its fruit's segments. The bearing tree and the mature fruit's size are somewhat larger than the trees and fruit of other varieties of citron.