The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is an ocean current that flows clockwise from west to east around Antarctica. An alternative name for the ACC is the West Wind Drift. The ACC is the dominant circulation feature of the Southern Ocean and has a mean transport estimated at 100–150 Sverdrups, or possibly even higher, making it the largest ocean current. The current is circumpolar due to the lack of any landmass connecting with Antarctica and this keeps warm ocean waters away from Antarctica, enabling that continent to maintain its huge ice sheet.

Antarctic krill is a species of krill found in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is the dominant animal species of Earth. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000–30,000 individual animals per cubic metre. It feeds directly on minute phytoplankton, thereby using the primary production energy that the phytoplankton originally derived from the sun in order to sustain their pelagic life cycle. It grows to a length of 6 centimetres (2.4 in), weighs up to 2 grams (0.071 oz), and can live for up to six years. It is a key species in the Antarctic ecosystem and in terms of biomass, is one of the most abundant animal species on the planet.

Zooplankton are heterotrophic plankton. Plankton are organisms drifting in oceans, seas, and bodies of fresh water. The word zooplankton is derived from the Greek zoon (ζῴον), meaning "animal", and planktos (πλαγκτός), meaning "wanderer" or "drifter". Individual zooplankton are usually microscopic, but some are larger and visible to the naked eye.

The Ordovician–Silurian extinction events, also known as the Late Ordovician mass extinction, are collectively the second-largest of the five major extinction events in Earth's history in terms of percentage of genera that became extinct. Extinction was global during this period, eliminating 49–60% of marine genera and nearly 85% of marine species. Only the Permian-Triassic mass extinction exceeds the Late Ordovician mass extinction in biodiversity loss. The extinction event abruptly affected all major taxonomic groups and caused the disappearance of one third of all brachiopod and bryozoan families, as well as numerous groups of conodonts, trilobites, echinoderms, corals, bivalves, and graptolites. This extinction was the first of the "big five" Phanerozoic mass extinction events and was the first to significantly affect animal-based communities. However, the Late Ordovician mass extinction did not produce major changes to ecosystem structures compared to other mass extinctions, nor did it lead to any particular morphological innovations. Diversity gradually recovered to pre-extinction levels over the first 5 million years of the Silurian period.

Ice algae are any of the various types of algal communities found in annual and multi-year sea or terrestrial ice. On sea ice in the polar oceans, ice algae communities play an important role in primary production. The timing of blooms of the algae is especially important for supporting higher trophic levels at times of the year when light is low and ice cover still exists. Sea ice algal communities are mostly concentrated in the bottom layer of the ice, but can also occur in brine channels within the ice, in melt ponds, and on the surface.

The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone which correlates to the upper Adelaide and lower Tarkastad Subgroups of the Beaufort Group, a fossiliferous and geologically important geological Group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. This biozone has outcrops in the south central Eastern Cape and in the southern and northeastern Free State. The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is one of eight biozones found in the Beaufort Group, and is considered to be Early Triassic in age.

In certain species of diatoms, auxospores are specialised cells that are produced at key stages in their cell cycle or life history. Auxospores typically play a role in growth processes, sexual reproduction or dormancy.

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mainly by rivers but also by dust carried by wind and by the flow of glaciers into the sea. Additional deposits come from marine organisms and chemical precipitation in seawater, as well as from underwater volcanoes and meteorite debris.

The ocean quahog is a species of edible clam, a marine bivalve mollusk in the family Arcticidae. This species is native to the North Atlantic Ocean, and it is harvested commercially as a food source. This species is also known by a number of different common names, including Icelandic cyprine, mahogany clam, mahogany quahog, black quahog, and black clam.

Siliceous ooze is a type of biogenic pelagic sediment located on the deep ocean floor. Siliceous oozes are the least common of the deep sea sediments, and make up approximately 15% of the ocean floor. Oozes are defined as sediments which contain at least 30% skeletal remains of pelagic microorganisms. Siliceous oozes are largely composed of the silica based skeletons of microscopic marine organisms such as diatoms and radiolarians. Other components of siliceous oozes near continental margins may include terrestrially derived silica particles and sponge spicules. Siliceous oozes are composed of skeletons made from opal silica Si(O2), as opposed to calcareous oozes, which are made from skeletons of calcium carbonate organisms (i.e. coccolithophores). Silica (Si) is a bioessential element and is efficiently recycled in the marine environment through the silica cycle. Distance from land masses, water depth and ocean fertility are all factors that affect the opal silica content in seawater and the presence of siliceous oozes.

The Ordovician radiation, or the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE), was an evolutionary radiation of animal life throughout the Ordovician period, 40 million years after the Cambrian explosion, whereby the distinctive Cambrian fauna fizzled out to be replaced with a Paleozoic fauna rich in suspension feeder and pelagic animals.

The Lopez de Bertodano Formation is a geological formation in the James Ross archipelago of the Antarctic Peninsula. The strata date from the end of the Late Cretaceous to the Danian stage of the lower Paleocene, from about 70 to 65.5 million years ago, straddling the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary.

Limacina rangii is a species of swimming sea snail in the family Limacinidae, which belong to the group commonly known as sea butterflies (Thecosomata).

Olev Vinn is Estonian paleobiologist and paleontologist.

Particulate organic matter (POM) is a fraction of total organic matter operationally defined as that which does not pass through a filter pore size that typically ranges in size from 0.053 and 2 milimeters.

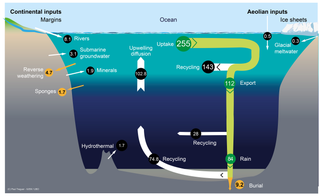

The silica cycle is the biogeochemical cycle in which biogenic silica is transported between the Earth's systems. Opal silica (SiO2) is a chemical compound of silicon, and is also called silicon dioxide. Silicon is considered a bioessential element and is one of the most abundant elements on Earth. The silica cycle has significant overlap with the carbon cycle (see carbonate–silicate cycle) and plays an important role in the sequestration of carbon through continental weathering, biogenic export and burial as oozes on geologic timescales.

The Tasmanian Passage, also Tasmanian Gateway or Tasmanian Seaway, is the name of ocean waters between Australia and Antarctica.

Fragilariopsis cylindrus is a pennate sea-ice diatom that is found native in the Argentine Sea and Antarctic waters, with a pH of 8.1-8.4. It is regarded as an indicator species for polar water.

Particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) can be contrasted with dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), the other form of inorganic carbon found in the ocean. These distinctions are important in chemical oceanography. Particulate inorganic carbon is sometimes called suspended inorganic carbon. In operational terms, it is defined as the inorganic carbon in particulate form that is too large to pass through the filter used to separate dissolved inorganic carbon.

The Great Calcite Belt (GCB) of the Southern Ocean is a region of elevated summertime upper ocean calcite concentration derived from coccolithophores, despite the region being known for its diatom predominance. The overlap of two major phytoplankton groups, coccolithophores and diatoms, in the dynamic frontal systems characteristic of this region provides an ideal setting to study environmental influences on the distribution of different species within these taxonomic groups.