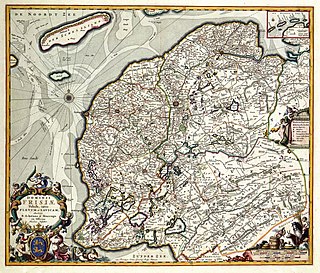

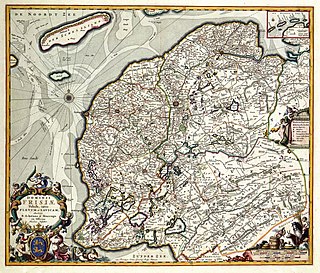

Friesland, historically and traditionally known as Frisia, named after the Frisians, is a province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen, northwest of Drenthe and Overijssel, north of Flevoland, northeast of North Holland, and south of the Wadden Sea. As of January 2023, the province had a population of about 660,000, and a total area of 5,753 km2 (2,221 sq mi).

Forseti is the god of justice and reconciliation in Norse mythology. He is generally identified with Fosite, a god of the Frisians.

The Frisians are an ethnic group indigenous to the coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark, and during the Early Middle Ages in the north-western coastal zone of Flanders, Belgium. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany, East Frisia and North Frisia.

Frisia is a cross-border cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. Wider definitions of "Frisia" may include the island of Rem and the other Danish Wadden Sea Islands. The region is traditionally inhabited by the Frisians, a West Germanic ethnic group.

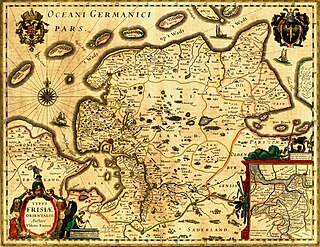

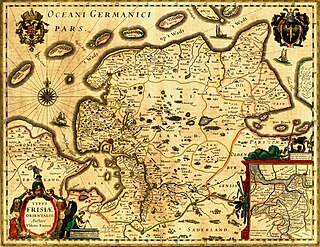

East Frisia or East Friesland is a historic region in modern Lower Saxony, Germany. The modern province is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia and to the west of Landkreis Friesland but is known to have extended much further inland before modern representations of the territory. Administratively, East Frisia consists of the districts Aurich, Leer and Wittmund and the city of Emden. It has a population of approximately 469,000 people and an area of 3,142 square kilometres (1,213 sq mi).

Eala Frya Fresena is the motto for the coat of arms of East Frisia in northern Germany. The motto is often mistranslated as "Hail, free Frisians!", but it was the reversal of the feudal prostration and is better translated as "Stand up, free Frisians!". According to 16th century sources, it was spoken at the Upstalsboom in Aurich where Frisian judges meet on Pentecost and it is traditionally answered with Lever dood as Slaav, or in English, rather dead than slaves.

Podestà, also potestate or podesta in English, was the name given to the holder of the highest civil office in the government of the cities of central and northern Italy during the Late Middle Ages. Sometimes, it meant the chief magistrate of a city-state, the counterpart to similar positions in other cities that went by other names, e.g. rettori ('rectors').

Medieval communes in the European Middle Ages had sworn allegiances of mutual defense among the citizens of a town or city. These took many forms and varied widely in organization and makeup.

The Rheiderland is a region of Germany and the Netherlands between the River Ems and the Bay of Dollart. The German part of the Rheiderland lies in East Frisia, west of the Ems. The Dutch part lies in the Dutch province of Groningen and is mostly part of Oldambt. The Rheiderland is one of the four historic regions on the mainland in the district of Leer; the others being the Overledingerland, the Moormerland and the Lengenerland.

Magnus Forteman was the legendary first potestaat and commander of Frisia which is now part of Germany and the Netherlands. His existence is based on a saga's writings.

Karelsprivilege is a legendary privilege that Charlemagne allegedly paid to the Frisians led by Magnus Forteman to thank them for the support that was given to his attack on Rome. Since the 13th century, the Frisians regularly mentioned Karelsprivilege in legal and historical works. The authenticity of the privilege has been heavily contested, especially after the Middle Ages. The privilege formed the basis of the so-called Frisian freedom. It was recognized as genuine by a number of Holy Roman emperors. An affirmation and recognition of the privilege was given by Emperor Conrad II in 1039.

Frisia is a small region in the north of the modern day country known as the Netherlands. In the Iron Age, the ancestors of the modern Frisians first migrated south out of modern day Scandinavia to the south west where they began to settle along the coast. The archeological record goes all the way back to the Neolithic era, however, the first written sources for Frisian history come from Roman records, like Tacitus' account of an unsuccessful Frisian attack on a Roman fort. Frisia would go on to distinguish itself culturally from other Germanic peoples but remained recognizably Germanic nonetheless. In the Early Medieval era, Frisians took the seas with well crafted ships to perform trade and to raid other ports, cities, and towns in other parts of Europe. For most of its modern history, Frisia, or Frysland, has been under the control of the Netherlands but today their language is co-official with Dutch at the provincial level. Frisian is the most closely related language to English aside from Scots.

The County of East Frisia was a county in the region of East Frisia in the northwest of the present-day German state of Lower Saxony.

The Frisian–Frankish wars were a series of conflicts between the Frankish Empire and the Frisian kingdom in the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Frisian Kingdom is a modern name for the post-Roman Frisian realm in Western Europe in the period when it was at its largest (650–734). This dominion was ruled by kings and emerged in the mid-7th century and probably ended with the Battle of the Boarn in 734 when the Frisians were defeated by the Frankish Empire. It lay mainly in what is now the Netherlands and – according to some 19th century authors – extended from the Zwin near Bruges in Belgium to the Weser in Germany. The center of power was the city of Utrecht.

The Lordship of Groningen was a lordship under the rule of the House of Habsburg between 1536 and 1594, which is the present-day province of Groningen.

The Lordship of Frisia or Lordship of Friesland was a feudal dominion in the Netherlands. It was formed in 1498 by King Maximilian I and reformed in 1524 when Emperor Charles V conquered Frisia.

Frisian nationalism refers to the nationalism which views Frisians as a nation with a shared culture. Frisian nationalism seeks to achieve greater levels of autonomy for Frisian people, and also supports the cultural unity of all Frisians regardless of modern-day territorial borders. The Frisians derive their name from the Frisii, an ancient Germanic tribe which inhabited the northern coastal areas in what today is the northern Netherlands, although historical research has indicated a lack of direct ethnic continuity between the ancient Frisii and later medieval 'Frisians' from whom modern Frisians descend. In the Middle Ages, these Frisians formed the Kingdom of Frisia and later the Frisian freedom confederation, before being subsumed by stronger foreign powers up to this day.

The Netherlands in the early Middle Ages was inhabited by various Germanic tribes, including the Frisians, who played a significant role in the development of the region and its Christianisation and eventual incorporation into the Frankish Empire.