Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are interwoven affects the characteristics of the cloth. Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.

Ikat is a dyeing technique from Indonesia used to pattern textiles that employs resist dyeing on the yarns prior to dyeing and weaving the fabric. The term is also used to refer to related and unrelated traditions in other cultures. In Southeast Asia, where it is the most widespread, ikat weaving traditions can be divided into two general clades. The first is found among Daic-speaking peoples. The second, larger group is found among the Austronesian peoples and spread via the Austronesian expansion. Similar dyeing and weaving techniques that developed independently are also present in other regions of the world, including India, Central Asia, Japan, Africa, and the Americas.

In the manufacture of cloth, warp and weft are the two basic components in weaving to transform thread and yarn into textile fabrics. The vertical warp yarns are held stationary in tension on a loom (frame) while the horizontal weft is drawn through the warp thread. In the terminology of weaving, each warp thread is called a warp end ; a pick is a single weft thread that crosses the warp thread.

Double cloth or double weave is a kind of woven textile in which two or more sets of warps and one or more sets of weft or filling yarns are interconnected to form a two-layered cloth. The movement of threads between the layers allows complex patterns and surface textures to be created.

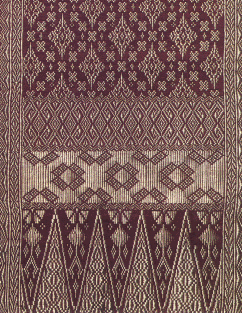

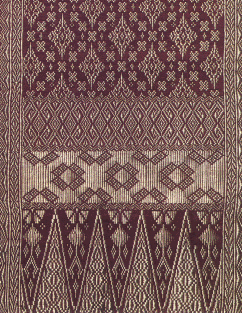

Songket or sungkit is a tenun fabric that belongs to the brocade family of textiles of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. It is hand-woven in silk or cotton, and intricately patterned with gold or silver threads. The metallic threads stand out against the background cloth to create a shimmering effect. In the weaving process the metallic threads are inserted in between the silk or cotton weft (latitudinal) threads in a technique called supplementary weft weaving technique.

Kasuri (絣) is the Japanese term for fabric that has been woven with fibers dyed specifically to create patterns and images in the fabric, typically referring to fabrics produced within Japan using this technique. It is a form of ikat dyeing, traditionally resulting in patterns characterized by their blurred or brushed appearance.

The manufacture of textiles is one of the oldest of human technologies. To make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fiber from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. The yarn is processed by knitting or weaving, which turns yarn into cloth. The machine used for weaving is the loom. For decoration, the process of colouring yarn or the finished material is dyeing. For more information of the various steps, see textile manufacturing.

A sampot, a long, rectangular cloth worn around the lower body, is a traditional dress in Cambodia. It can be draped and folded in several different ways. The traditional dress is similar to the dhoti of Southern Asia. It is also worn in the neighboring countries of Laos and Thailand where it is known as pha nung.

Samite was a luxurious and heavy silk fabric worn in the Middle Ages, of a twill-type weave, often including gold or silver thread. The word was derived from Old French samit, from medieval Latin samitum, examitum deriving from the Byzantine Greek ἑξάμιτον hexamiton "six threads", usually interpreted as indicating the use of six yarns in the warp. Samite is still used in ecclesiastical robes, vestments, ornamental fabrics, and interior decoration.

The Bali Aga, Baliaga, or Bali Mula are the indigenous people of Bali. Linguistically they are an Austronesian people. Bali Aga people are predominantly located in the eastern part of the island, in Bangli, Buleleng and Karangasem, but they can also be found in north-western and central regions. Bali Aga people who are referred to as Bali Pergunungan are those that are located at Trunyan village. For the Trunyan Bali Aga people, the term Bali Aga is regarded as an insult with an additional meaning of "the mountain people that are fools"; therefore, they prefer the term Bali Mula instead.

A Sambalpuri sari is a traditional handwoven bandha (ikat) sari wherein the warp and the weft are tie-dyed before weaving. It is produced in the Sambalpur, Balangir, Bargarh, Boudh and Sonepur districts of Odisha, India. The sari is a traditional female garment in the Indian subcontinent consisting of a strip of unstitched cloth ranging from four to nine meters in length that is draped over the body in various styles.

Tenganan Pegringsingan or Pageringsingan is a village in the regency of Karangasem in East Bali, Indonesia. Before the 1970s was known by anthropologists to be a secluded society in the archipelago.

The national costume of Indonesia is the national attire that represents the Republic of Indonesia. It is derived from Indonesian culture and Indonesian traditional textile traditions. Today the most widely recognized Indonesian national attires include batik and kebaya, although originally those attires mainly belong within the island of Java and Bali, most prominently within Javanese, Sundanese and Balinese culture. Since Java has been the political and population center of Indonesia, folk attire from the island has become elevated into national status.

Amuzgo textiles are those created by the Amuzgo indigenous people who live in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca. The history of this craft extends to the pre-Columbian period, which much preserved, as many Amuzgos, especially in Xochistlahuaca, still wear traditional clothing. However, the introduction of cheap commercial cloth has put the craft in danger as hand woven cloth with elaborate designs cannot compete as material for regular clothing. Since the 20th century, the Amuzgo weavers have mostly made cloth for family use, but they have also been developing specialty markets, such as to collectors and tourists for their product.

Balinese textiles are reflective of the historical traditions of Bali, Indonesia. Bali has been historically linked to the major courts of Java before the 10th century; and following the defeat of the Majapahit kingdom, many of the Javanese aristocracy fled to Bali and the traditions were continued. Bali therefore may be seen as a repository not only of its own arts but those of Java in the pre-Islamic 15th century. Any attempt to definitively describe Balinese textiles and their use is doomed to be incomplete. The use of textile is a living tradition and so is in constant change. It will also vary from one district to another. For the most part old cloth are not venerated for their age. New is much better. In the tropics cloth rapidly deteriorates and so virtue is generated by replacing them.

The textiles of Sumba, an island in eastern Indonesia, represent the means by which the present generation passes on its messages to future generations. Sumbanese textiles are deeply personal; they follow a distinct systematic form but also show the individuality of the weavers and the villages where they are produced. Internationally, Sumbanese textiles are collected as examples of textile designs of the highest quality and are found in major museums around the world, as well as in the homes of collectors.

A Patola sari is a double ikat woven sari, usually made from silk, made in Patan, Gujarat, India. The word patola is the plural form; the singular is patolu. These saris are made using silk threads that are first dyed with natural colors and then woven together to create the intricate patterns and designs. They are usually worn for special occasions, such as weddings and formal events.

Odisha Ikat, is a kind of ikat known as Bandhakala and Bandha, a resist dyeing technique, originating from Indian state of Odisha. Traditionally known as "Bandhakala"', "Bandha", '"Bandha of Odisha", it is a geographically tagged product of Odisha since 2007. It is made through a process of tie-dyeing the warp and weft threads to create the design on the loom prior to weaving. It is unlike any other ikat woven in the rest of the country because of its design process, which has been called "poetry on the loom". This design is in vogue only at the western and eastern regions of Odisha; similar designs are produced by community groups called the Bhulia, Kostha Asani, and Patara. The fabric gives a striking curvilinear appearance. Saris made out of this fabric feature bands of brocade in the borders and also at the ends, called anchal or pallu. Its forms are purposefully feathered, giving the edges a "hazy and fragile" appearance. There are different kinds of bandha saris made in Odisha, notably Khandua, Sambalpuri, Pasapali, Kataki and Manibandhi.

"Narrow cloth" is cloth of a comparatively narrow width, generally less than a human armspan; precise definitions vary.

Meisen is a type of silk fabric traditionally produced in Japan; it is durable, hard-faced, and somewhat stiff, with a slight sheen, and slubbiness is deliberately emphasised. Meisen was first produced in the late 19th century, and became widely popular during the 1920s and 30s, when it was mass-produced and ready-to-wear kimono began to be sold in Japan. Meisen is commonly dyed using kasuri techniques, and features what were then overtly modern, non-traditional designs and colours. Meisen remained popular through to the 1950s.