In fluid dynamics, a vortex is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in the wake of a boat, and the winds surrounding a tropical cyclone, tornado or dust devil.

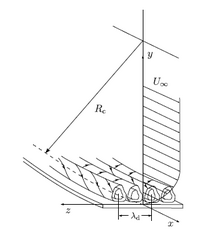

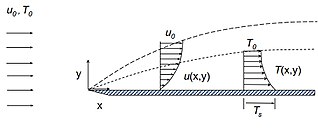

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces a no-slip boundary condition. The flow velocity then monotonically increases above the surface until it returns to the bulk flow velocity. The thin layer consisting of fluid whose velocity has not yet returned to the bulk flow velocity is called the velocity boundary layer.

A vortex ring, also called a toroidal vortex, is a torus-shaped vortex in a fluid; that is, a region where the fluid mostly spins around an imaginary axis line that forms a closed loop. The dominant flow in a vortex ring is said to be toroidal, more precisely poloidal.

In fluid dynamics, a Kármán vortex street is a repeating pattern of swirling vortices, caused by a process known as vortex shedding, which is responsible for the unsteady separation of flow of a fluid around blunt bodies.

In fluid dynamics, the Taylor–Couette flow consists of a viscous fluid confined in the gap between two rotating cylinders. For low angular velocities, measured by the Reynolds number Re, the flow is steady and purely azimuthal. This basic state is known as circular Couette flow, after Maurice Marie Alfred Couette, who used this experimental device as a means to measure viscosity. Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor investigated the stability of Couette flow in a ground-breaking paper. Taylor's paper became a cornerstone in the development of hydrodynamic stability theory and demonstrated that the no-slip condition, which was in dispute by the scientific community at the time, was the correct boundary condition for viscous flows at a solid boundary.

In fluid dynamics, Batchelor vortices, first described by George Batchelor in a 1964 article, have been found useful in analyses of airplane vortex wake hazard problems.

The Dean number (De) is a dimensionless group in fluid mechanics, which occurs in the study of flow in curved pipes and channels. It is named after the British scientist W. R. Dean, who was the first to provide a theoretical solution of the fluid motion through curved pipes for laminar flow by using a perturbation procedure from a Poiseuille flow in a straight pipe to a flow in a pipe with very small curvature.

In physical oceanography, Langmuir circulation consists of a series of shallow, slow, counter-rotating vortices at the ocean's surface aligned with the wind. These circulations are developed when wind blows steadily over the sea surface. Irving Langmuir discovered this phenomenon after observing windrows of seaweed in the Sargasso Sea in 1927. Langmuir circulations circulate within the mixed layer; however, it is not yet so clear how strongly they can cause mixing at the base of the mixed layer.

In fluid dynamics, a Stokes wave is a nonlinear and periodic surface wave on an inviscid fluid layer of constant mean depth. This type of modelling has its origins in the mid 19th century when Sir George Stokes – using a perturbation series approach, now known as the Stokes expansion – obtained approximate solutions for nonlinear wave motion.

Double diffusive convection is a fluid dynamics phenomenon that describes a form of convection driven by two different density gradients, which have different rates of diffusion.

A vortex sheet is a term used in fluid mechanics for a surface across which there is a discontinuity in fluid velocity, such as in slippage of one layer of fluid over another. While the tangential components of the flow velocity are discontinuous across the vortex sheet, the normal component of the flow velocity is continuous. The discontinuity in the tangential velocity means the flow has infinite vorticity on a vortex sheet.

Three-dimension losses and correlation in turbomachinery refers to the measurement of flow-fields in three dimensions, where measuring the loss of smoothness of flow, and resulting inefficiencies, becomes difficult, unlike two-dimensional losses where mathematical complexity is substantially less.

In fluid dynamics, the Burgers vortex or Burgers–Rott vortex is an exact solution to the Navier–Stokes equations governing viscous flow, named after Jan Burgers and Nicholas Rott. The Burgers vortex describes a stationary, self-similar flow. An inward, radial flow, tends to concentrate vorticity in a narrow column around the symmetry axis, while an axial stretching causes the vorticity to increase. At the same time, viscous diffusion tends to spread the vorticity. The stationary Burgers vortex arises when the three effects are in balance.

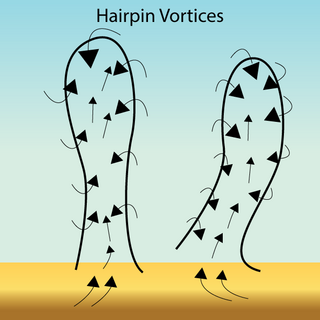

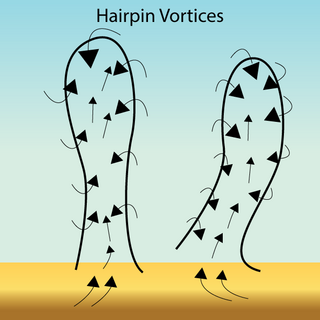

Turbulent flows are complex multi-scale and chaotic motions that need to be classified into more elementary components, referred to coherent turbulent structures. Such a structure must have temporal coherence, i.e. it must persist in its form for long enough periods that the methods of time-averaged statistics can be applied. Coherent structures are typically studied on very large scales, but can be broken down into more elementary structures with coherent properties of their own, such examples include hairpin vortices. Hairpins and coherent structures have been studied and noticed in data since the 1930s, and have been since cited in thousands of scientific papers and reviews.

In fluid dynamics, the Craik–Leibovich (CL) vortex force describes a forcing of the mean flow through wave–current interaction, specifically between the Stokes drift velocity and the mean-flow vorticity. The CL vortex force is used to explain the generation of Langmuir circulations by an instability mechanism. The CL vortex-force mechanism was derived and studied by Sidney Leibovich and Alex D. D. Craik in the 1970s and 80s, in their studies of Langmuir circulations.

Von Kármán swirling flow is a flow created by a uniformly rotating infinitely long plane disk, named after Theodore von Kármán who solved the problem in 1921. The rotating disk acts as a fluid pump and is used as a model for centrifugal fans or compressors. This flow is classified under the category of steady flows in which vorticity generated at a solid surface is prevented from diffusing far away by an opposing convection, the other examples being the Blasius boundary layer with suction, stagnation point flow etc.

In fluid dynamics Jeffery–Hamel flow is a flow created by a converging or diverging channel with a source or sink of fluid volume at the point of intersection of the two plane walls. It is named after George Barker Jeffery(1915) and Georg Hamel(1917), but it has subsequently been studied by many major scientists such as von Kármán and Levi-Civita, Walter Tollmien, F. Noether, W.R. Dean, Rosenhead, Landau, G.K. Batchelor etc. A complete set of solutions was described by Edward Fraenkel in 1962.

In fluid dynamics, a stagnation point flow refers to a fluid flow in the neighbourhood of a stagnation point or a stagnation line with which the stagnation point/line refers to a point/line where the velocity is zero in the inviscid approximation. The flow specifically considers a class of stagnation points known as saddle points wherein incoming streamlines gets deflected and directed outwards in a different direction; the streamline deflections are guided by separatrices. The flow in the neighborhood of the stagnation point or line can generally be described using potential flow theory, although viscous effects cannot be neglected if the stagnation point lies on a solid surface.

In fluid dynamics, Stokes problem also known as Stokes second problem or sometimes referred to as Stokes boundary layer or Oscillating boundary layer is a problem of determining the flow created by an oscillating solid surface, named after Sir George Stokes. This is considered one of the simplest unsteady problems that has an exact solution for the Navier–Stokes equations. In turbulent flow, this is still named a Stokes boundary layer, but now one has to rely on experiments, numerical simulations or approximate methods in order to obtain useful information on the flow.

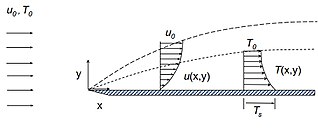

This page describes some parameters used to characterize the properties of the thermal boundary layer formed by a heated fluid moving along a heated wall. In many ways, the thermal boundary layer description parallels the velocity (momentum) boundary layer description first conceptualized by Ludwig Prandtl. Consider a fluid of uniform temperature and velocity impinging onto a stationary plate uniformly heated to a temperature . Assume the flow and the plate are semi-infinite in the positive/negative direction perpendicular to the plane. As the fluid flows along the wall, the fluid at the wall surface satisfies a no-slip boundary condition and has zero velocity, but as you move away from the wall, the velocity of the flow asymptotically approaches the free stream velocity . The temperature at the solid wall is and gradually changes to as one moves toward the free stream of the fluid. It is impossible to define a sharp point at which the thermal boundary layer fluid or the velocity boundary layer fluid becomes the free stream, yet these layers have a well-defined characteristic thickness given by and . The parameters below provide a useful definition of this characteristic, measurable thickness for the thermal boundary layer. Also included in this boundary layer description are some parameters useful in describing the shape of the thermal boundary layer.