Dunnockshaw or Dunnockshaw and Clowbridge is a civil parish in the borough of Burnley, in Lancashire, England. The parish is situated between Burnley and Rawtenstall. According to the United Kingdom Census 2011, the parish has a population of 185.

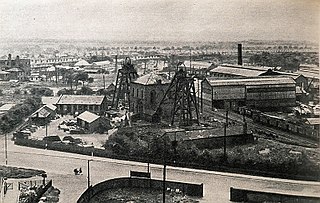

Tower Colliery was the oldest continuously working deep-coal mine in the United Kingdom, and possibly the world, until its closure in 2008. It was the last mine of its kind to remain in the South Wales Valleys. It was located near the villages of Hirwaun and Rhigos, north of the town of Aberdare in the Cynon Valley of South Wales.

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

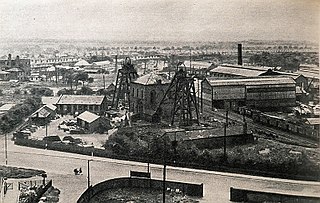

Agecroft Colliery was a coal mine on the Manchester Coalfield that opened in 1844 in the Agecroft district of Pendlebury, Lancashire, England. It exploited the coal seams of the Middle Coal Measures of the Lancashire Coalfield. The colliery had two spells of use; the first between 1844 and 1932, when the most accessible coal seams were exploited, and a second lease of life after extensive development in the late 1950s to access the deepest seams.

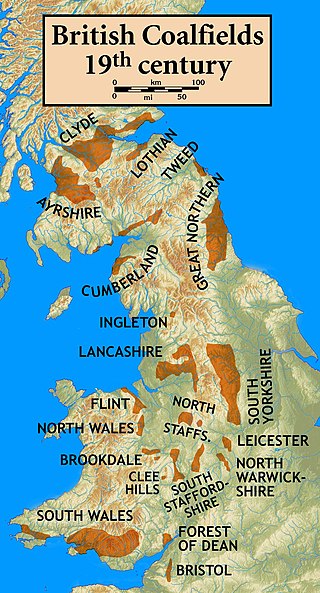

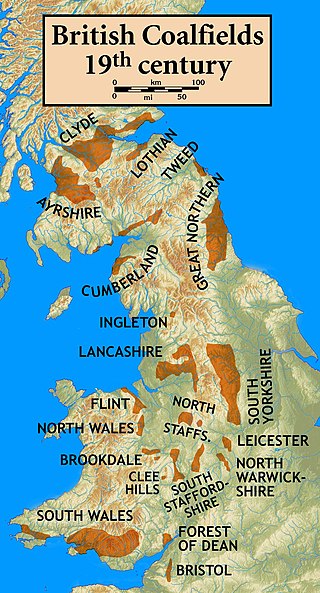

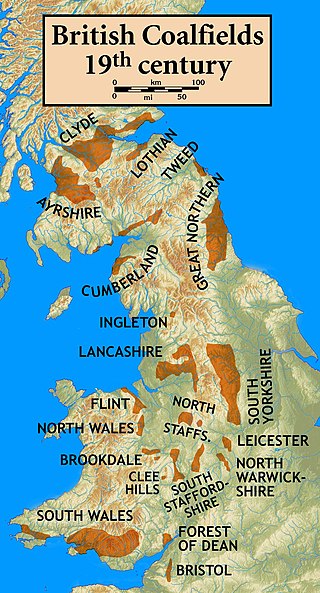

The South Yorkshire Coalfield is so named from its position within Yorkshire. It covers most of South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire and a small part of North Yorkshire. The exposed coalfield outcrops in the Pennine foothills and dips under Permian rocks in the east. Its most famous coal seam is the Barnsley Bed. Coal has been mined from shallow seams and outcrops since medieval times and possibly earlier.

Chatterley Whitfield Colliery is a disused coal mine on the outskirts of Chell, Staffordshire in Stoke on Trent, England. It was the largest mine working the North Staffordshire Coalfield and was the first colliery in the UK to produce one million tons of saleable coal in a year.

The Minnie Pit disaster was a coal mining accident that took place on 12 January 1918 in Halmer End, Staffordshire, in which 155 men and boys died. The disaster, which was caused by an explosion due to firedamp, is the worst ever recorded in the North Staffordshire Coalfield. An official investigation never established what caused the ignition of flammable gases in the pit.

The Lancashire Coalfield in North West England was an important British coalfield. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period over 300 million years ago.

The Ingleton Coalfield is in North Yorkshire, close to its border with Lancashire in north-west England. Isolated from other coal-producing areas, it is one of the smallest coalfields in Great Britain.

Bedford Colliery, also known as Wood End Pit, was a coal mine on the Manchester Coalfield in Bedford, Leigh, Lancashire, England. The colliery was owned by John Speakman, who started sinking two shafts on land at Wood End Farm in the northeast part of Bedford, south of the London and North Western Railway's Tyldesley Loopline in about 1874. Speakman's father owned Priestners, Bankfield, and Broadoak collieries in Westleigh. Bedford Colliery remained in the possession of the Speakman family until it was amalgamated with Manchester Collieries in 1929.

Bickershaw Colliery was a coal mine, located on Plank Lane in Leigh, then within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire, England.

Pendleton Colliery was a coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield after the late 1820s on Whit Lane in Pendleton, Salford, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

Bradford Colliery was a coal mine in Bradford, Manchester, England. Although part of the Manchester Coalfield, the seams of the Bradford Coalfield correspond more closely to those of the Oldham Coalfield. The Bradford Coalfield is crossed by a number of fault lines, principally the Bradford Fault, which was reactivated by mining activity in the mid-1960s.

The Tarenni Colliery and its associated workings, are a series of coal mines and pits located between the villages of Godre'r Graig and Cilybebyll located in the valley of the River Tawe, in Neath Port Talbot county borough, South Wales.

Hameldon Hill is a Carboniferous sandstone hill with a summit elevation of 409 metres (1,342 ft), situated between the towns of Burnley and Accrington in Lancashire, England. It is listed as a "HuMP" or "Hundred Metre Prominence", its parent being Freeholds Top, a Marilyn near Bacup.

This is a partial glossary of coal mining terminology commonly used in the coalfields of the United Kingdom. Some words were in use throughout the coalfields, some are historic and some are local to the different British coalfields.

The Burnley Coalfield is the most northerly portion of the Lancashire Coalfield. Surrounding Burnley, Nelson, Blackburn and Accrington, it is separated from the larger southern part by an area of Millstone Grit that forms the Rossendale anticline. Occupying a syncline, it stretches from Blackburn past Colne to the Yorkshire border where its eastern flank is the Pennine anticline.

Bank Hall Colliery was a coal mine on the Burnley Coalfield in Burnley, Lancashire near the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Sunk in the late 1860s, it was the town's largest and deepest pit and had a life of more than 100 years.

Ellesmere Colliery was a coal mine in Walkden, Manchester, England. The pit was located on Manchester Road, a short distance south of Walkden town centre.