Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation, a schism in the Western Church. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental, Presbyterian, and Congregational traditions, as well as parts of the Anglican and Baptist traditions.

The Protestant Church in the Netherlands is the largest Protestant denomination in the Netherlands, being both Calvinist and Lutheran.

Total depravity is a Protestant theological doctrine derived from the concept of original sin. It teaches that, as a consequence of the Fall, every person born into the world is enslaved to the service of sin as a result of their fallen nature and, apart from the efficacious (irresistible) or prevenient (enabling) grace of God, is completely unable to choose by themselves to follow God, refrain from evil, or accept the gift of salvation as it is offered.

The Dutch Reformed Church was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the traditional denomination of the Dutch royal family and the foremost Protestant denomination until 2004, the year it helped found and merged into the Protestant Church in the Netherlands. It was the larger of the two major Reformed denominations, after the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands was founded in 1892. It spread to the United States, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and various other world regions through Dutch colonization. Allegiance to the Dutch Reformed Church was a common feature among Dutch immigrant communities around the world and became a crucial part of Afrikaner nationalism in South Africa.

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of those members of the Lutheran Church in Germany who were accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Luther in 1546. It denotes what was seen as a hidden Calvinist belief, i.e., the doctrines of John Calvin, by members of the Lutheran Church. The term crypto-Calvinist in Lutheranism was preceded by terms Zwinglian and Sacramentarian. Also, Jansenism has been accused of crypto-Calvinism by Roman Catholics.

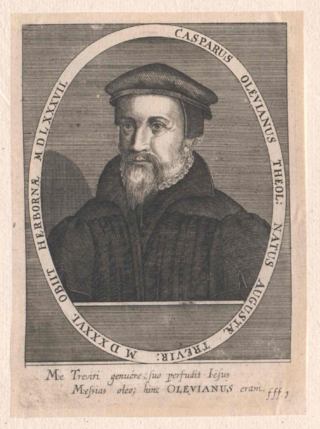

Caspar Olevian was a significant German Reformed theologian during the Protestant Reformation and along with Zacharias Ursinus was said to be co-author of the Heidelberg Catechism. That theory of authorship has been questioned by some modern scholarship.

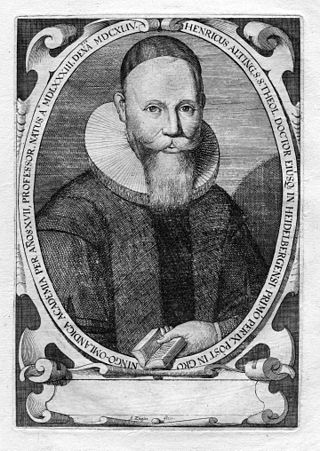

Johann Heinrich Alting, German divine, was born at Emden, where his father, Menso Alting (1541–1612), was minister.

The Reformed Church in the United States (RCUS) is a Protestant Christian denomination in the United States. The present RCUS is a conservative, Calvinist denomination. It affirms the principles of the Reformation: Sola scriptura, Solus Christus, Sola gratia, Sola fide, and Soli Deo gloria. The RCUS has membership concentrated in the Midwest and California.

The Evangelical and Reformed Church (E&R) was a Protestant Christian denomination in the United States. It was formed in 1934 by the merger of the Reformed Church in the United States (RCUS) with the Evangelical Synod of North America (ESNA). A minority within the RCUS remained out of the merger in order to continue the name Reformed Church in the United States. In 1957, the Evangelical and Reformed Church merged with the majority of the Congregational Christian Churches (CC) to form the United Church of Christ (UCC).

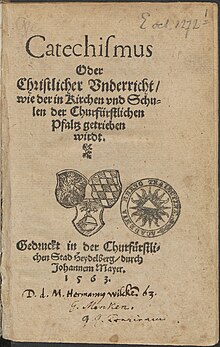

Zacharias Ursinus was a sixteenth-century German Reformed theologian and Protestant reformer, born Zacharias Baer in Breslau. He became the leading theologian of the Reformed Protestant movement of the Palatinate, serving both at the University of Heidelberg and the College of Wisdom. He is best known as the principal author and interpreter of the Heidelberg Catechism.

Frederick III of Simmern, the Pious, Elector Palatine of the Rhine was a ruler from the house of Wittelsbach, branch Palatinate-Simmern-Sponheim. He was a son of John II of Simmern and inherited the Palatinate from the childless Elector Otto-Henry, Elector Palatine (Ottheinrich) in 1559. He was a devout convert to Calvinism, and made the Reformed confession the official religion of his domain by overseeing the composition and promulgation of the Heidelberg Catechism. His support of Calvinism gave the German Reformed movement a foothold within the Holy Roman Empire.

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

The Three Forms of Unity is a collective name for the Belgic Confession, the Canons of Dort, and the Heidelberg Catechism, which reflect the doctrinal concerns of continental Calvinism and are accepted as official statements of doctrine by many Calvinist churches.

Reformed Christianity originated with the Reformation in Switzerland when Huldrych Zwingli began preaching what would become the first form of the Reformed doctrine in Zürich in 1519.

Abraham Scultetus was a German professor of theology, and the court preacher for the Elector of the Palatinate Frederick V.

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that identifies primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church ended the Middle Ages and, in 1517, launched the Reformation.

Pierre Boquin was a French Reformed Theologian who played a critical role in the Reformation of the Electoral Palatinate.

Tilemann Heshusius was a Gnesio-Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Johann Wigand was a German Lutheran cleric, Protestant reformer and theologian. He served as Bishop of Pomesania.

Reformed orthodoxy or Calvinist orthodoxy was an era in the history of Calvinism in the 16th to 18th centuries. Calvinist orthodoxy was paralleled by similar eras in Lutheranism and tridentine Roman Catholicism after the Counter-Reformation. Calvinist scholasticism or Reformed scholasticism was a theological method that gradually developed during the era of Calvinist Orthodoxy.