| Demographics and culture of Hong Kong |

|---|

| Demographics |

| Culture |

| Other Hong Kong topics |

A Hong Kong returnee is a resident of Hong Kong who emigrated to another country, lived for an extended period of time in his or her adopted home, and then subsequently moved back to Hong Kong.

According to the Hong Kong Transition Project of Hong Kong Baptist University, in 2002, Hong Kong returnees constituted 3% of the Hong Kong population. [1] This number was arrived at by survey and a participant was categorised as a "returnee" by self-identification. As such, it excluded those Hong Kongers surveyed who had foreign citizenship, but did not self-identify as "returnees".

Most returnees left Hong Kong during the 1980s and the 1990s leading up to the handover of Hong Kong back to China. According to Matthew Cheung, Secretary for Labour and Welfare, approximately 600,000 people emigrated before and around 1997. [2] The destination of choice was usually a Western country, the most popular being Canada, Australia, and the United States.

There are typically two types of emigrants, those who planned on returning to Hong Kong after they obtained foreign citizenship and those who planned on staying in their adopted homes permanently and fully adapting to life there. The former are sometimes better described as sojourners rather than emigrants. However, often these two types of Hong Kong emigrants act against what they had planned, where some of those who had planned on permanent stays actually returned to Hong Kong, some planning on temporary stays actually made the decision to stay permanently in their adopted homelands.

It is estimated that 30% of those Hong Kongers who moved away in the 1980s have returned to Hong Kong. [3] Those that have moved back to Hong Kong have returned for various reasons – for economic reasons, or simply because they enjoy living in Hong Kong more than they do elsewhere. Specifically, many wealthy Hong Kongers who emigrated to Canada found that they could not adjust to the economic culture in Canada. The higher taxes, red tape, and the language contributed to the barrier of entry for businesses in Canada. Comparatively speaking, doing business in Hong Kong was much easier.

The movement of people is not a permanent remigration as returnees could go back to their adopted country at any stage, especially if they gained its citizenship. Plans to return to their adopted homeland could be influenced by political or personal reasons. [4]

Issues of identity have sometimes arisen for returnees, especially amongst those returnees that left Hong Kong when they were children, because of the change in national identity of Hong Kong the city itself due to Hong Kong returning to Chinese rule, and because of the life experiences gained living in their previously adopted homes outside of Hong Kong.

Many of those who returned to Hong Kong were husbands who left their entire families in their adopted homes, while they worked in Hong Kong. These husbands were dubbed Taai Hung Yahn (Chinese :太空人; Cantonese Yale :taai hùng yàhn), or "astronauts" because they spend their lives flying back and forth between Hong Kong and the adopted homes of their families.

Taai Hung Yahn is also a play on words. Taking a more literal meaning of the Chinese characters for "astronaut", Taai Hung Yahn (太空人) can translate loosely to "man without a wife".

Demographic features of the population of Hong Kong include population density, ethnicity, education level, the health of the populace, religious affiliations, and other aspects.

Overseas Chinese people are those of Chinese birth or ethnicity who reside outside mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese. Overall, China has a low percent of population living overseas.

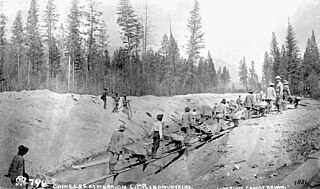

Chinese immigrants began settling in Canada in the 1780s. The major periods of Chinese immigration would take place from 1858 to 1923 and 1947 to the present day, reflecting changes in the Canadian government's immigration policy.

The culture of Hong Kong is primarily a mix of Chinese and Western influences, stemming from Lingnan Cantonese roots and later fusing with British culture due to British colonialism. As an international financial center dubbed "Asia's World City", contemporary Hong Kong has also absorbed many international influences from around the world. Moreover, Hong Kong also has indigenous people and ethnic minorities from South and Southeast Asia, whose cultures all play integral parts in modern-day Hong Kong culture. As a result, after the 1997 transfer of sovereignty to the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong has continued to develop a unique identity under the rubric of One Country, Two Systems.

Yerida is emigration by Jews from the State of Israel. Yerida is the opposite of aliyah, which is immigration by Jews to Israel. Zionists are generally critical of the act of yerida and the term is somewhat derogatory. The emigration of non-Jewish Israelis is not included in the term.

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation are separated from the relationship between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Some nations domestically use the terms interchangeably, though by the 20th century, nationality had commonly come to mean the status of belonging to a particular nation with no regard to the type of governance which established a relationship between the nation and its people. In law, nationality describes the relationship of a national to the state under international law and citizenship describes the relationship of a citizen within the state under domestic statutes. Different regulatory agencies monitor legal compliance for nationality and citizenship. A person in a country of which he or she is not a national is generally regarded by that country as a foreigner or alien. A person who has no recognised nationality to any jurisdiction is regarded as stateless.

British nationality law as it pertains to Hong Kong has changed over time since it became a British colony in 1842. Hongkongers were given various nationality statuses, such as British subjects, Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies, British Dependent Territories Citizen and British Nationals (Overseas).

Britons never made up more than a small portion of the population in Hong Kong, despite Hong Kong having been under British rule for more than 150 years. However, they did leave their mark on Hong Kong's institutions, culture and architecture. The British population in Hong Kong today consists mainly of career expatriates working in banking, education, real estate, law and consultancy, as well as many British-born ethnic Chinese, former Chinese émigrés to the UK and Hong Kongers who successfully applied for full British citizenship before the transfer of sovereignty in 1997.

Chinese nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds nationality of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The primary law governing these requirements is the Nationality Law of the People's Republic of China, which came into force on September 10, 1980.

The Hong Kong identity card is an official identity document issued by the Immigration Department of Hong Kong. According to the Registration of Persons Ordinance, all residents of age 11 or above who are living in Hong Kong for longer than 180 days must, within 30 days of either reaching the age of 11 or arriving in Hong Kong, register for an HKID. HKIDs contain amongst others the name of the bearer in English, and if applicable in Chinese. The HKID does not expire for the duration of residency in Hong Kong.

The Touch Base Policy was an immigration policy in British Hong Kong from 1974 to 1980 towards the Refugee wave from the People's Republic of China to British Hong Kong. Under the policy, illegal immigrants from China could stay in Hong Kong if they reached urban areas and found a home with their relatives or other forms of accommodation.

The United States consulate estimates there are about 70,000 Americans in Hong Kong as of January 2023, a drop from 85,000 since its 2018 estimate; no census by any US government organization has ever been attempted. They consist of both native-born Americans of various ethnic backgrounds, including Chinese Americans and Hong Kong Americans, as well as former Hong Kong emigrants of Chinese descent to the United States who returned after gaining American citizenship. Many come to Hong Kong on work assignments; others study at local universities. They form a large part of the greater community of Americans in China.

Emigration from Hong Kong refers to the migration of Hong Kong residents away from Hong Kong. Reasons for migration range from livelihood hardships, such as the high cost of living and educational pressures, to economic opportunities elsewhere, such as expanded opportunities in mainland China following the Reform and Opening-Up, to various political events, such as the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong during the Second World War, the 1967 unrest, uncertainties leading up to the 1997 handover, and the 2019–2020 unrest. The largest community of Hong Kongers living outside of Hong Kong is in Mainland China, followed by the US, Canada and the UK.

The British diaspora consists of people of English, Scottish, Welsh, Northern Irish, Cornish, Manx and Channel Islands ancestral descent who live outside of the United Kingdom and its Crown Dependencies.

Hongkongers, Hong Kongers, Hong Kongese, Hongkongese, Hong Kong citizens and Hong Kong people are demonyms that refer to a resident of Hong Kong, although they may also refer to others who were born and/or raised in the territory.

Migration of Chinese people in Ghana dates back to the 1940s. Originally, most came from Hong Kong; migration from mainland China began only in the 1980s.

Return migration refers to the individual or family decision of a migrant to leave a host country and to return permanently to the country of origin. Research topics include the return migration process, motivations for returning, the experiences returnees encounter, and the impacts of return migration on both the host and the home countries.

Hong Kong Canadians are Canadians who were born or raised in Hong Kong, hold permanent residency in Hong Kong, or trace their ancestry back to Hong Kong. In Canada, the majority of Hong Kong Canadians reside in the metropolitan areas of Toronto and Vancouver. Many Hong Kong Canadians continue to maintain their status as Hong Kong permanent residents.

An astronaut family is a family unit where the members reside in different countries across the world—in contrast to a "nuclear family". The astronaut family represents the growing transnationalism of peoples' identities that accompanies the growing globalization.

Hong Kong Americans, include Americans who are also Hong Kong residents who identify themselves as Hong Kongers, Americans of Hong Kong ancestry, and also Americans who have Hong Kong parents.