Neurofibromatosis (NF) refers to a group of three distinct genetic conditions in which tumors grow in the nervous system. The tumors are non-cancerous (benign) and often involve the skin or surrounding bone. Although symptoms are often mild, each condition presents differently. Neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) is typically characterized by café au lait spots, neurofibromas, scoliosis, and headaches. Neurofibromatosis type II (NF2), on the other hand, may present with early-onset hearing loss, cataracts, tinnitus, difficulty walking or maintain balance, and muscle atrophy. The third type is called schwannomatosis and often presents in early adulthood with widespread pain, numbness, or tingling due to nerve compression.

Tietz syndrome, also called Tietz albinism-deafness syndrome or albinism and deafness of Tietz, is an autosomal dominant congenital disorder characterized by deafness and leucism. It is caused by a mutation in the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) gene. Tietz syndrome was first described in 1963 by Walter Tietz (1927–2003) a German Physician working in California.

Variegate porphyria, also known by several other names, is an autosomal dominant porphyria that can have acute symptoms along with symptoms that affect the skin. The disorder results from low levels of the enzyme responsible for the seventh step in heme production. Heme is a vital molecule for all of the body's organs. It is a component of hemoglobin, the molecule that carries oxygen in the blood.

Lamellar ichthyosis, also known as ichthyosis lamellaris and nonbullous congenital ichthyosis, is a rare inherited skin disorder, affecting around 1 in 600,000 people.

Adenosine deaminase deficiency is a metabolic disorder that causes immunodeficiency. It is caused by mutations in the ADA gene. It accounts for about 10–20% of all cases of autosomal recessive forms of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) after excluding disorders related to inbreeding.

Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD) is a rare, autosomal recessive form of muscular dystrophy (weakness and breakdown of muscular tissue) mainly described in Japan but also identified in Turkish and Ashkenazi Jewish patients; fifteen cases were first described on 1960 by Dr. Yukio Fukuyama.

Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome is a disorder that affects development of the limbs, head, and face. The features of this syndrome are highly variable, ranging from very mild to severe. People with this condition typically have one or more extra fingers or toes (polydactyly) or an abnormally wide thumb or big toe (hallux).

Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome (PLS), also known as palmoplantar keratoderma with periodontitis, is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a deficiency in cathepsin C.

White sponge nevus (WSN) is an autosomal dominant condition of the oral mucosa. It is caused by one or more mutations in genes coding for keratin, which causes a defect in the normal process of keratinization of the mucosa. This results in lesions which are thick, white and velvety on the inside of the cheeks within the mouth. Usually, these lesions are present from birth or develop during childhood. The condition is benign and usually requires no treatment. WSN can, however, predispose affected individuals to over-growth/imbalance of the oral microbiota, which may require antibiotic and/or antifungal treatment.

Naegeli–Franceschetti–Jadassohn syndrome (NFJS), also known as chromatophore nevus of Naegeli and Naegeli syndrome, is a rare autosomal dominant form of ectodermal dysplasia, characterized by reticular skin pigmentation, diminished function of the sweat glands, the absence of teeth and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. One of the most striking features is the absence of fingerprint lines on the fingers.

Dermatopathia pigmentosa reticularis(DPR) is a rare, autosomal dominant congenital disorder that is a form of ectodermal dysplasia. Dermatopathia pigmentosa reticularis is composed of the triad of generalized reticulate hyperpigmentation, noncicatricial alopecia, and onychodystrophy. DPR is a non life-threatening disease that largely affects the skin, hair, and nails. It has also been identified as a keratin disorder. Historically, as of 1992, only 10 cases had been described in world literature; however, due to recent advances in genetic analysis, five additional families studied in 2006 have been added to the short list of confirmed cases.

Pachyonychia congenita is a rare group of autosomal dominant skin disorders that are caused by a mutation in one of five different keratin genes. Pachyonychia congenita is often associated with thickened toenails, plantar keratoderma, and plantar pain.

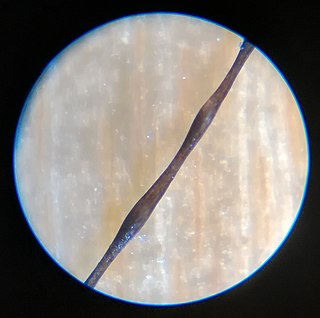

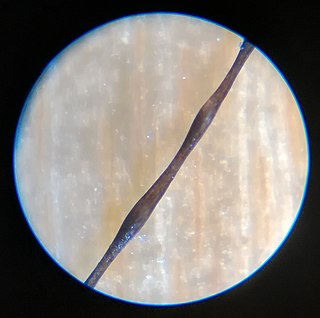

Monilethrix is a rare autosomal dominant hair disease that results in short, fragile, broken hair that appears beaded. It comes from the Latin word for necklace (monile) and the Greek word for hair (thrix). Hair becomes brittle, and breaks off at the thinner parts between the beads. It appears as a thinning or baldness of hair and was first described in 1897 by Walter Smith

Rothmund–Thomson syndrome (RTS) is a rare autosomal recessive skin condition.

Steatocystoma multiplex, is a benign, autosomal dominant congenital condition resulting in multiple cysts on a person's body. Steatocystoma simplex is the solitary counterpart to steatocystoma multiplex.

Woodhouse–Sakati syndrome, is a rare autosomal recessive multisystem disorder which causes malformations throughout the body, and deficiencies affecting the endocrine system.

Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, also known as nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, is a rare type of the ichthyosis family of skin diseases which occurs in 1 in 200,000 to 300,000 births. The disease comes under the umbrella term autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis, which include non-syndromic congenital ichthyoses such as harlequin ichthyosis and lamellar ichthyosis.

Gillespie syndrome, also called aniridia, cerebellar ataxia and mental deficiency, is a rare genetic disorder. The disorder is characterized by partial aniridia, ataxia, and, in most cases, intellectual disability. It is heterogeneous, inherited in either an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive manner. Gillespie syndrome was first described by American ophthalmologist Fredrick Gillespie in 1965.

Nakajo syndrome, also called nodular erythema with digital changes, is a rare autosomal recessive congenital disorder first reported in 1939 by A. Nakajo in the offspring of consanguineous parents. The syndrome can be characterized by erythema, loss of body fat in the upper part of the body, and disproportionately large eyes, ears, nose, lips, and fingers.

Parastremmatic dwarfism is a rare bone disease that features severe dwarfism, thoracic kyphosis, a distortion and twisting of the limbs, contractures of the large joints, malformations of the vertebrae and pelvis, and incontinence. The disease was first reported in 1970 by Leonard Langer and associates; they used the term parastremmatic from the Greek parastremma, or distorted limbs, to describe it. On X-rays, the disease is distinguished by a "flocky" or lace-like appearance to the bones. The disease is congenital, which means it is apparent at birth. It is caused by a mutation in the TRPV4 gene, located on chromosome 12 in humans. The disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.