Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Venezuela face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Venezuela, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Also, same-sex marriage and de facto unions are constitutionally banned since 1999.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Chile have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now quite progressive.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Spain rank among the highest in the world, having undergone significant advancements within recent decades. Among ancient Romans in Spain, sexual interaction between men was viewed as commonplace, but a law against homosexuality was promulgated by Christian emperors Constantius II and Constans, and Roman moral norms underwent significant changes leading up to the 4th century. Laws against sodomy were later established during the legislative period. They were first repealed from the Spanish Code in 1822, but changed again along with societal attitudes towards homosexuality during the Spanish Civil War and Francisco Franco's regime.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Costa Rica have evolved significantly in the past decades. Same-sex sexual relations have been legal since 1971. In January 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights made mandatory the approbation of same-sex marriage, adoption for same-sex couples and the removal of people's sex from all Costa Rican ID cards issued since October 2018. The Costa Rican Government announced that it would apply the rulings in the following months. In August 2018, the Costa Rican Supreme Court ruled against the country's same-sex marriage ban, and gave the Legislative Assembly 18 months to reform the law accordingly, otherwise the ban would be abolished automatically. Same-sex marriage became legal on 26 May 2020.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Mexico expanded in the 21st century, keeping with worldwide legal trends. The intellectual influence of the French Revolution and the brief French occupation of Mexico (1862–67) resulted in the adoption of the Napoleonic Code, which decriminalized same-sex sexual acts in 1871. Laws against public immorality or indecency, however, have been used to prosecute persons who engage in them.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Argentina rank among the highest in the world. Upon legalising same-sex marriage on 15 July 2010, Argentina became the first country in Latin America, the second in the Americas, and the tenth in the world to do so. Following Argentina's transition to a democracy in 1983, its laws have become more inclusive and accepting of LGBT people, as has public opinion.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Uruguay rank among the highest in the world. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal with an equal age of consent since 1934. Anti-discrimination laws protecting LGBT people have been in place since 2004. Civil unions for same-sex couples have been allowed since 2008 and same-sex marriages since 2013, in accordance with the nation's same-sex marriage law passed in early 2013. Additionally, same-sex couples have been allowed to jointly adopt since 2009 and gays, lesbians and bisexuals are allowed to serve openly in the military. Finally, in 2018, a new law guaranteed the human rights of the trans population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Colombia have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now quite progressive. Consensual same-sex sexual activity in Colombia was decriminalized in 1981. Between February 2007 and April 2008, three rulings of the Constitutional Court granted registered same-sex couples the same pension, social security and property rights as registered heterosexual couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Nicaragua face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Nicaragua. Discrimination based on sexual orientation is banned in certain areas, including in employment and access to health services.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, non-binary and otherwise queer, non-cisgender, non-heterosexual citizens of El Salvador face considerable legal and social challenges not experienced by fellow heterosexual, cisgender Salvadorans. While same-sex sexual activity between all genders is legal in the country, same-sex marriage is not recognized; thus, same-sex couples—and households headed by same-sex couples—are not eligible for the same legal benefits provided to heterosexual married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Peru face some legal challenges not experienced by other residents. Same-sex sexual activity among consenting adults is legal. However, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

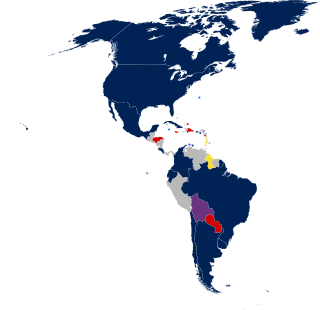

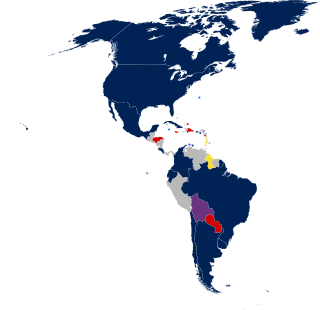

Laws governing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are complex and diverse in the Americas, and acceptance of LGBTQ persons varies widely.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Ecuador since 8 July 2019 in accordance with a Constitutional Court ruling issued on 12 June 2019 that the ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional under the Constitution of Ecuador. The court held that the Constitution required the government to license and recognise same-sex marriages. It focused its ruling on an advisory opinion issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in January 2018 that member states should grant same-sex couples "accession to all existing domestic legal systems of family registration, including marriage, along with all rights that derive from marriage". The ruling took effect upon publication in the government gazette on 8 July.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Dominican Republic do not possess the same legal protections as non-LGBTQ residents, and face social challenges that are not experienced by other people. While the Dominican Criminal Code does not expressly prohibit same-sex sexual relations or cross-dressing, it also does not address discrimination or harassment on the account of sexual orientation or gender identity, nor does it recognize same-sex unions in any form, whether it be marriage or partnerships. Households headed by same-sex couples are also not eligible for any of the same rights given to opposite-sex married couples, as same-sex marriage is constitutionally banned in the country.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Bolivia have expanded significantly in the 21st century. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity and same-sex civil unions are legal in Bolivia. The Bolivian Constitution bans discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2016, Bolivia passed a comprehensive gender identity law, seen as one of the most progressive laws relating to transgender people in the world.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Guatemala face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Guatemala.

El Salvador does not recognize same-sex marriage, civil unions or any other legal union for same-sex couples. A proposal to constitutionally ban same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples was rejected twice in 2006, and once again in April 2009 after the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) refused to grant the measure the four votes it needed to be ratified.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Paraguay face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Paraguay, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for all of the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Paraguay remains one of the few conservative countries in South America regarding LGBT rights.

This article presents a timeline of the most relevant events in the history of LGBT people in Ecuador. The earliest manifestations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Ecuador were in the pre-Columbian era, in cultures such as Valdivia, Tumaco-La Tolita, and Bahía, of which evidence has been found suggesting that homosexuality was common among its members. Documents by Hispanic chroniclers and historians—such as Pedro Cieza de León, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, and Garcilaso de la Vega—point to the Manteño-Huancavilca culture in particular as one in which homosexuality was openly practiced and accepted. However, with the Spanish conquest, a system of repression was established against anyone who practiced homosexuality in the territories that currently make up Ecuador.