Treatment of the regicides

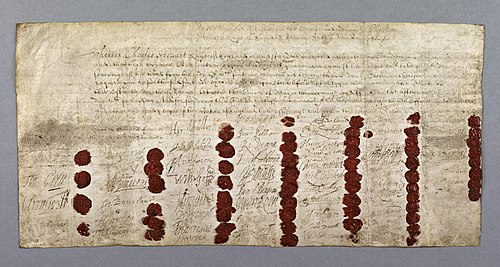

In 1660, Parliament passed the Indemnity and Oblivion Act, [c] which granted amnesty to many of those who had supported the Parliament during the Civil War and the Interregnum, although 104 people were specifically excluded. Of those, 49 named individuals and the two unknown executioners were to face a capital charge. According to Howard Nenner, writing for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , Charles would probably have been content with a smaller number to be punished, but Parliament took a strong line.

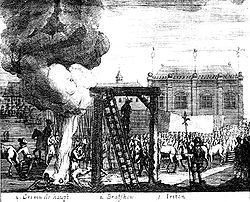

Of those who were listed to receive punishment, 24 had already died, including Cromwell, John Bradshaw, the judge who was president of the court, and Henry Ireton. They were given a posthumous execution: their remains were exhumed, and they were hanged, beheaded and their remains cast into a pit below the gallows. Their heads were placed on spikes above Westminster Hall, the building where the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I had sat. In 1660, six of the commissioners and four others were found guilty of regicide and executed. One was hanged and nine were hanged, drawn and quartered.

On Monday 15 October 1660, Pepys records in his diary that "this morning Mr Carew was hanged and quartered at Charing Cross; but his quarters, by a great favour, are not to be hanged up." Five days later he writes, "I saw the limbs of some of our new traitors set upon Aldersgate, which was a sad sight to see; and a bloody week this and the last have been, there being ten hanged, drawn, and quartered." In 1662, three more regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered. Some others were pardoned, while a further nineteen served life imprisonment. Most had their property confiscated and many were banned from holding office or title again in the future.

Twenty-one of those under threat fled Britain, mostly settling in the Netherlands or Switzerland, although some were captured and returned to England, or murdered by Royalist sympathisers. Three of the regicides, John Dixwell, Edward Whalley and William Goffe, fled to New England, where they avoided capture, despite a search. [d]

Nenner records that there is no agreed definition of who is included in the list of regicides. The Indemnity and Oblivion Act did not use the term either as a definition of the act, or as a label for those involved, [e] and historians have identified different groups of people as being appropriate for the name.

Shortly after the Restoration in Scotland, the Scottish Parliament passed an Act of Indemnity and Oblivion. It was similar to the English Indemnity and Oblivion Act, but there were many more exceptions under the Scottish act than there were under the English one. Most of the Scottish exceptions were pecuniary, and only four men were executed, all for treason but none for regicide, of whom the Marquess of Argyll was the most prominent. He was found to be guilty of collaboration with Cromwell's government, and beheaded on 27 May 1661.