Canadian nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Canada. The primary law governing these regulations is the Citizenship Act, which came into force on February 15, 1977 and is applicable to all provinces and territories of Canada.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court which held that "a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China", automatically became a U.S. citizen at birth. This decision established an important precedent in its interpretation of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

United States nationality law details the conditions in which a person holds United States nationality. In the United States, nationality is typically obtained through provisions in the U.S. Constitution, various laws, and international agreements. Citizenship is established as a right under the Constitution, not as a privilege, for those born in the United States under its jurisdiction and those who have been "naturalized". While the words citizen and national are sometimes used interchangeably, national is a broader legal term, such that a person can be a national but not a citizen, while citizen is reserved to nationals who have the status of citizenship.

Coverture was a legal doctrine in English common law originating from the French word couverture, meaning "covering," in which a married woman's legal existence was considered to be merged with that of her husband. Upon marriage, she had no independent legal existence of her own, in keeping with society's expectation that her husband was to provide for and protect her. Under coverture a woman became a feme covert, whose legal rights and obligations were mostly subsumed by those of her husband. An unmarried woman, or feme sole, retained the right to own property and make contracts in her own name.

The Cable Act of 1922 was a United States federal law that partially reversed the Expatriation Act of 1907. (It is also known as the Married Women's Citizenship Act or the Women's Citizenship Act). In theory the law was designed to grant women their own national identity; however, in practice, as it still retained vestiges of coverture, tying a woman's legal identity to her husband's, it had to be amended multiple times before it granted women citizenship in their own right.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 was a law of the United States Congress that set the first uniform rules for the granting of United States citizenship by naturalization. The law limited naturalization to "free white person(s) ... of good character", thus excluding Native Americans, indentured servants, enslaved people, free Africans, Pacific Islanders, and non-White Asians. This eliminated ambiguity on how to treat newcomers, given that free black people had been allowed citizenship at the state level in many states. In reading the Naturalization Act, the courts also associated whiteness with Christianity and thus excluded Muslim immigrants from citizenship until the decision Ex Parte Mohriez recognized citizenship for a Saudi Muslim man in 1944.

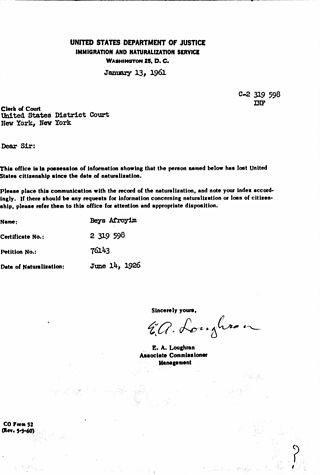

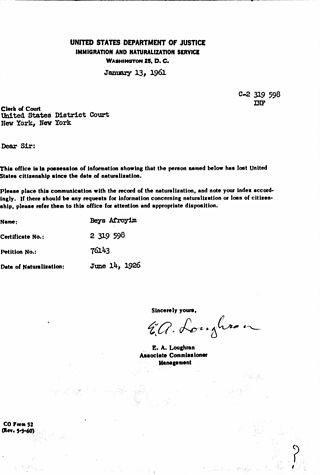

Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled that citizens of the United States may not be deprived of their citizenship involuntarily. The U.S. government had attempted to revoke the citizenship of Beys Afroyim, a man born in Poland, because he had cast a vote in an Israeli election after becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen. The Supreme Court decided that Afroyim's right to retain his citizenship was guaranteed by the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In so doing, the Court struck down a federal law mandating loss of U.S. citizenship for voting in a foreign election—thereby overruling one of its own precedents, Perez v. Brownell (1958), in which it had upheld loss of citizenship under similar circumstances less than a decade earlier.

Perez v. Brownell, 356 U.S. 44 (1958), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court affirmed Congress's right to revoke United States citizenship as a result of a citizen's voluntary performance of specified actions, even in the absence of any intent or desire on the person's part to lose citizenship. Specifically, the Supreme Court upheld an act of Congress which provided for revocation of citizenship as a consequence of voting in a foreign election.

United States citizenship can be acquired by birthright in two situations: by virtue of the person's birth within United States territory or because at least one of their parents was a U.S. citizen at the time of the person's birth. Birthright citizenship contrasts with citizenship acquired in other ways, for example by naturalization.

Philippine nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of the Philippines. The two primary pieces of legislation governing these requirements are the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines and the 1939 Revised Naturalization Law.

Renunciation of citizenship is the voluntary loss of citizenship. It is the opposite of naturalization, whereby a person voluntarily obtains citizenship. It is distinct from denaturalization, where citizenship is revoked by the state.

The Citizenship Clause is the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted on July 9, 1868, which states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court decision that established that a United States citizen cannot have their citizenship taken away unless they have acted with an intent to give up that citizenship. The Supreme Court overturned portions of an act of Congress which had listed various actions and had said that the performance of any of these actions could be taken as conclusive, irrebuttable proof of intent to give up U.S. citizenship. However, the Court ruled that a person's intent to give up citizenship could be established through a standard of preponderance of evidence — rejecting an argument that intent to relinquish citizenship could only be found on the basis of clear, convincing and unequivocal evidence.

Puerto Rico is an island in the Caribbean region in which inhabitants were Spanish nationals from 1508 until the Spanish–American War in 1898, from which point they derived their nationality from United States law. Nationality is the legal means by which inhabitants acquire formal membership in a nation without regard to its governance type; citizenship means the rights and obligations that each owes the other, once one has become a member of a nation. In addition to being United States nationals, persons are citizens of the United States and citizens of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico within the context of United States Citizenship. Miriam J. Ramirez de Ferrer v. Juan Mari Brás. Though the Constitution of the United States recognizes both national and state citizenship as a means of accessing rights, Puerto Rico's history as a territory has created both confusion over the status of its nationals and citizens and controversy because of distinctions between jurisdictions of the United States. These differences have created what political scientist Charles R. Venator-Santiago has called "separate and unequal" statuses.

Perkins v. Elg, 307 U.S. 325 (1939), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that a child born in the United States to naturalized parents on U.S. soil is a natural born citizen and that the child's natural born citizenship is not lost if the child is taken to and raised in the country of the parents' origin, provided that upon attaining the age of majority, the child elects to retain U.S. citizenship "and to return to the United States to assume its duties."

The Expatriation Act of 1868 was an act of the 40th United States Congress that declared, as part of the United States nationality law, that the right of expatriation is "a natural and inherent right of all people" and "that any declaration, instruction, opinion, order, or decision of any officers of this government which restricts, impairs, or questions the right of expatriation, is hereby declared inconsistent with the fundamental principles of this government".

The Expatriation Act of 1907 was an act of the 59th United States Congress concerning retention and relinquishment of United States nationality by married women and Americans residing abroad. It effectively functioned as Congressional endorsement of the various ad hoc rulings on loss of United States nationality that had been made by the State Department since the enactment of the Expatriation Act of 1868. Some sections of it were repealed by other acts in the early 1920s; those sections which remained were codified at 8 U.S.C. §§ 6–17, but those too were repealed by the Nationality Act of 1940 when the question of dual citizenship arose.

The Renunciation Act of 1944 was an act of the 78th Congress regarding the renunciation of United States citizenship. Prior to the law's passage, it was not possible to lose U.S. citizenship while in U.S. territory except by conviction for treason; the Renunciation Act allowed people physically present in the U.S. to renounce citizenship when the country was in a state of war by making an application to the Attorney General. The intention of the 1944 Act was to encourage Japanese American internees to renounce citizenship so that they could be deported to Japan.

Johann Breyer was a Czech-American tool and die maker and onetime SS-Totenkopfverbände concentration and death camp guard whom the United States Department of Justice Office of Special Investigations (OSI) unsuccessfully attempted to denaturalize and deport for his teenage service in the SS. His was considered the "most arcane and convoluted litigation in OSI history", owing to the convergence of three unusual legal factors in the case:

Under United States federal law, a U.S. citizen or national may voluntarily and intentionally give up that status and become an alien with respect to the United States. Relinquishment is distinct from denaturalization, which in U.S. law refers solely to cancellation of illegally procured naturalization.